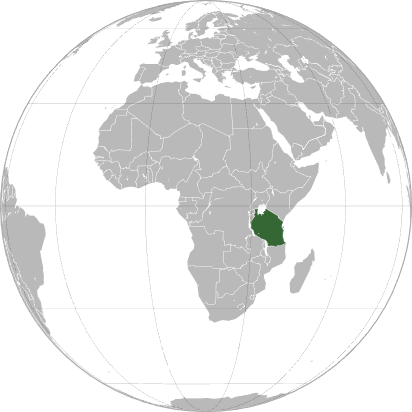

Situated on Africa’s Eastern coast, just below the equator, and with a surface of about 1 million km2, Tanzania is twice the size of France, but by no means one of Africa’s largest countries (Africa itself is three times the size of the US). About 56 million people live in Tanzania, a country in which over 100 languages are spoken (although Swahili is understood by almost everyone, since it’s taught in primary school and it’s the language used for all administrative duties).

Tanzania includes vast areas of wilderness and several beautiful islands, which we visited over a period of three weeks in March 2021.

Despite its large number of ethnic groups, and the tensions arising from the encroachment of territory by one group over the other, as well as the difficulty of ensuring the maintenance of zones exclusively reserved for wildlife, Tanzania is a very peaceful nation.

We loved the gentleness of the people, the food, the many breathtaking sites and of course the extraordinary wildlife of Tanzania. It’s a country that is less “manicured” for tourists than perhaps Kenya or South Africa, but this is what makes it charming and very authentic. Some of the hotels we stayed in were absolutely remarkable, among the most memorable we have ever seen.

We spent about half our time on mainland Tanzania, the rest was devoted to farniente on the islands of Unguja and Pemba, part of the Zanzibar group of islands, which are part of Tanzania since 1964.

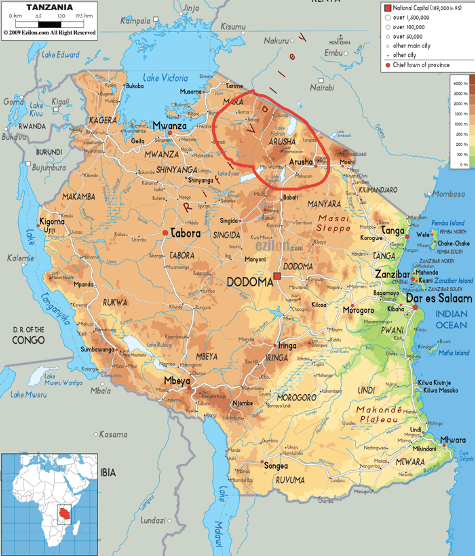

On mainland Tanzania, we started our trip in Arusha and visited an area to the west, bordering Kenya, and including Serengeti, Lake Manyara, Tarangire and Ngorongoro national parks/conservation areas.

We traveled in a very sturdy and slow-moving jeep, which could be opened at the top, allowing for extended views of the countryside and wildlife.

We are not people who like to sit in cars all day, but we found that our safari experience was not so bad. Somehow, almost every day we managed to walk 10’000 steps and we got frequent additional exercise by standing up and down in the jeep when the top was up.

Despite their sturdiness, the Tanzanian jeeps do get stuck in mud quite frequently, in which case other jeeps come to the rescue almost instantly.

Wildlife is all-pervasive and you have to be attentive because animals appear quickly (and often disappear just as quickly).

We found that the most interesting part of the safari was not so much to see the animals (you see them better in a David Attenborough documentary), but the stories about them. We were especially interested in the way in which they socialise. For example, elephants live in a matriarchal society, with males often, but not always, close to the females and the little ones, and mothers especially careful to protect their offspring, which is evident when as you watch this group crossing a street.

Elephants spend a lot of time bathing, which involves hours of throwing mud on themselves. The mud not only keeps them cool, but protects them from the many insects eager to nest on them:

In order to establish their dominance, males (especially younger ones) fight with each other, usually without seriously harming themselves.

Elephants are incredibly endearing and calm animals. We could have spent hours watching them.

Whereas gazelles prefer the savanna, where they feel protected by their speed and excellent long-distance eyesight, impalas (who also see well and are very fast), prefer thicker terrain. They are beautiful and gracious animals, with one dominant male in charge of a group of females. The rest of the males compete with each other for the privilege of living with the female harem. Uuuutanzank

Baboons are polygamous and live in large family groups. Unlike other primates, they live primarily on the ground, not on trees, so they are easier to see. They are an absolute delight to watch, especially when they groom one another (or when they copulate, which happens very frequently).

HBuffalos can move around in large crowds, especially on the prairies, but males lead a mostly solitary life, only occasionally joining the females and their cubs. Because of their size, they have few predators. They tend to feed at night, and spend their days in the shade. They are frequently accompanied by small white birds, who ride on them, and with whom they have a symbiotic relationship: the bird is offered protection and food, while the buffalo is freed from unwanted insects, who tend to nest on their fur, in areas which are difficult for the buffalo to reach.

Lions are very intelligent, but lazy animals – they sleep upto 20 hours per day. They hunt strategically and in a group, generally by ambushing their prey. They will not hesitate to intimidate other animals who have killed prey and eat their food, if it’s more convenient. After feasting for a few hours (or days), they will return to a slumbering mode, and mostly observe their territory from a high vantage point. Most of the hunting is done by females. Males tend to arrive once the work is over when it’s time to eat.

Giraffes move around in small groups, generally four or five at a time. Like elephants, they are excellent parents. When confronted with predators, they are able to kick formidably, and so are generally left in peace by lions and other large cats.

Rhinoceros lead mostly solitary lives. They are also endangered, so you don’t see many of them. We nevertheless saw a few. They are truly imposing animals, which you should avoid messing around with, as the video below shows (not filmed by us!):

Gnous, like zebras and antilopes, tend to move around in large herds, thereby offering them protection for predators, such as lions and other cats. Occasionally, a gnou or a zebra will be left behind, offering a perfect meal to a lion.

Cheetas are majestic animals, who can spend long hours scouting their territory before they attack. They are solitary, getting together only occasionally for mating. The mother keeps the cubs hidden in dens, while she spends what is sometimes a long time away hunting. Cheetahs get along well with humans, and in certain parts of Africa, cheetahs are domesticated. We had the unforgettable experience of watching a female cheetah for an extended period of time, from just a few metres away.

Hippopotamus are difficult to see. During the day they mostly stay in the water, huddling together in large groups, with only their eyes visible. When on land, like buffalos, they are often accompanied by small birds, who feed on the insects that settle on the hippo’s skin. The best way to see them is by flying over them in the early hours of the morning:

Tanzania is full of birds and one of the most delightful parts of our trip was when the car stopped and we just listened to the birds sing. One of the surprising things about our safari, was the peace we experienced in the midst of the national parks and conservation areas.

The southern hemisphere has many more stars than the northern one. In places like Serengeti or Ngorongoro, where there are few trees, the landscape is flat and there are practically no lights, we were in awe of the multitude of stars and often asked the driver to stop in the middle of the road, to just watch the tingling lights and the incredibly peaceful atmosphere. Before going to sleep, we always spent a few minutes observing the night lights from the window of our hotel room.

The areas where large wildlife is present (especially the savannah) is very calm. Animals will shy away from zones with noise (or light), which is why villages are such a problem for the preservation of wildlife. While picturesque, the villages, as they grow, will tend to push the wildlife away. The Tanzanian government is dealing with this issue, but the solutions are not easy.

Present-day mainland Tanzania is the birthplace of many of the earliest hominids. We visited the Olduvai Gorge Museum on a day when there were practically no visitors, and had the good fortune that an experienced curator spent a few hours with us, taking us through the most recent discoveries in the area.

At Olduvai, due to wind erosion, you can see geological strata going back almost two million years. This is why it’s one of the most important archeological sites on earth.

One of the most remarkable things we learned is that homo habilis, who lived in the area from about 2.3 to 1.6 million years ago, was much taller than we are. This is due to a diet which was much higher in meat than is the case for us today. It was homo habilis who developed the first tools with which to butcher animals and, importantly, it was this hominid who succeeded in domesticating fire, something that fundamentally transformed our species. It was also homo habilis who lost his body hair, thereby allowing him to hunt large prey during the hot hours of the day. Of all the hominids, this is the one that really transformed our heritage and evolved us into a position of dominance.

Homo habilis also initiated the (often rapid) extermination of large wildlife, and it was during this time that the first hominids started to exit Africa, pushed by climate change and the reduction in wildlife.

Africa is the only continent where large animals still exist in great numbers. This is because zebras, giraffes, gnous, antilopes and other large prey cohabited with hominids for an extended period of time, allowing them to realise that this little monkey was, in fact, very dangerous. This made them avoid us. In other parts of the world, when our ancestors arrived with their weapons and cooperative group hunting techniques, large wildlife was quickly wiped out. This is especially true for America and Australia, where humans arrived most recently and large game was wiped out very fast.

Our travel through mainland Tanzania was especially fascinating because we encountered so many different ethnic groups. We spent a considerable amount of time with the Hadza, Maasai and Datoga tribes.

The Hadza are one of the few remaining hunter gatherer tribes. We had the extraordinary experience of spending a morning with them, accompanying the men on one of their hunting expeditions.

The Hadza live in small huts made with grass and sticks, but many sleep outside, under the trees. They are monogamous, but change partners frequently. When a male and a female want to cohabitate, they just build a little hut and live there. Should the couple no longer get along, either the male or the female is free to choose another partner, with whom a new hut is built. The children are raised communally.

They have a unique language, which is unwritten, and is quite melodious. It frequently uses click sounds.

When Christian missionaries approached the Hadza, they listened, but concluded that Christianity was not for them. In their eyes, paradise, as described in Genesis, aptly described the world in which they lived, so the story of Adam and Eve and the rest of the Bible surely had nothing to do with them, it must have been intended for other people, certainly not the Hadza!

The community moves its site every few months, depending on weather conditions and the availability of food.

Every day, the women dig for roots and other edible plants or fruit, while the men hunt for prey.

Fire is made quickly and with considerable skill by heating a stone with a stick.

Because the Hadza don’t store food (everything they find during the day is consumed), there was no food consumed before the hunting expedition started. When we arrived, at about 6.30 am, everyone was quietly sitting around the fire chatting, the men on one side, the women on the other.

The hunt, in which about a dozen boys and men participated (we had trouble ascertaining their precise ages) was preceded by careful preparation of bows and arrows, which the Hadza make with wood from trees. They use their teeth to twist and bend the wood until it’s perfectly straight.

Once they left the camp, the hunters moved quickly and we had to walk fast to keep up with them.

During the hunt, the men occasionally stopped to gather other foodstuffs. We were impressed by their skill at finding little berries and at using barks of trees. One of the boys shared with us a thick juice coming out of a small shrub – it tasted just like chewing gum! The Hadza use this to clean their teeth.

After about an hour, the Hadza had killed five or six small birds. It took incredible skill to find the birds, who hide well in the trees, and then to hit them with the arrows. Once a bird has been hit, it is proudly shown to the others by the hunter. The birds were carried on their belts by the hunter or another member of the party, often a smaller boy.

Before returning to the camp, the hunters stopped, lit a fire, plucked one of the birds and with considerable skill roasted it on the flames. The hunter who has killed the bird can choose first what to eat (in our case, he chose the head and the heart), but everybody gets to eat and every part of the bird is eaten. We were given a small part of the breast and it was absolutely delicious!

Upon return to the camp, everyone rushed to see what the boys had caught and then the whole village began to dance. We were invited too!

Once the dancing ended, our guide asked us to say a few words. We said how moved we had been by what we had seen – how incredibly skilled the hunters were, how kind they had been to share their food with us and how the peace of their village had touched us. We said that they should be proud of their lifestyle and that we sincerely hoped that they would continue to thrive and live the life they did, that they were an example to the many who live unhealthy lives in cramped and sometimes dangerous cities.

There was a lot of applause when the the little speech was finished, but we left the Hadza with a feeling that it might not be long before these wonderful people would not be able to live the way they now do. There are only about 1’000 to 1’500 Hadza left, their territory has been reduced enormously, and there is also illegal encroachment into the zones reserved to them, by other tribes who raise cattle. Even if there is no encroachment, the larger wild animals that they depend on for food, tend to stay away if they hear sounds and lights from nearby villages. Finally, the government is trying to get the Hadza children into the Tanzanian schooling system, which will further dislocate their strong sense of identity.

We will never forget our morning with the Hadza, their gentleness towards each other and towards us, their wonderful (often shy, but always curious) looks and the simplicity of their world.

The Maasai are one of the larger tribes found in Tanzania, and we encountered them frequently as we travelled around.

One one occasion, and thanks to the fact that Onesmo, one of our two guides, is himself a Maasai, we were able to visit one of their villages.

The Maasai are generally tall. They are a nomadic tribe, which throughout the year follow their cattle (cows and goats) in search of pastures. Once they decide to settle in a certain area, the women build mud huts, while the men take care of the animals.

We visited one of the mud huts and were surprised by how cool it was inside. There are generally no doors and very little light, this in order to discourage insects from entering.

Men and especially women, wear brightly coloured clothes with many distinctive patterns. We were unable to tell the difference, but when a Maasai meets his kinsmen, he can easily tell which area he is from by the colours of the garments and the decorations that women wear.

In honour of Onesmo and to receive us, the Maasai organised a meal for us. It consisted almost exclusively of meat from a goat which they had slaughtered earlier that day. The food was primarily cooked over an open fire, although some of the interior organs were boiled in water. Only men were present.

The Maasai use no plates. Most of the meat is carved with a knife directly from the stick on which it cooked and then eaten by hand, but the boiled meat is put on leaves, left to rest and be cut there.

There is a protocol for eating: first guests, then one by one the tribe members are offered food by the village leader, who eats last.

After the meat is eaten, the bark of a special tree is added to the liquid in which the heart and other interior organs were cooked, and the water is boiled again. This mixture is then beaten into a froth with a stick, then consumed. It’s very bitter, but not bad at all. It’s supposed to help with digestion (it worked for us!).

Polygamy is important to the Maasai because it has significant material consequences. More wives means more children, which means that more cattle can be tended to and owned.

Marriages are arranged amongst families and dowries are paid by males, usually in the form of one or several cows and/or goats.

As the other tribes we saw, the Maasai were wonderfully welcoming and insisted in leaving us a present, even though we brought nothing to them. Evelyn left their village with a very beautiful bead bracelet.

The Maasai, as well as many other tribes, wear sandals made out of used tires. These are sold to measure in markets all over Tanzania and are surprisingly comfortable, sturdy and resilient.

Like the Maasai, the Datoga live in mud huts, but since they are a sedentary, their huts are bigger. Like the Maasai, they are polygamous, but their source of wealth is more diversified. While the Maasai’s wealth is almost entirely based on the herds they raise, the Datoga also farm maize, beans and millet. They are also skilled craftsmen.

We visited a Daroga ironmonger. We were amazed at the skill with which he and his son created spear-heads, which they sell to the Hadza, who need them to hunt larger animals, but are not able to manufacture metal objects.

The Datoga homes, like the Maasai’s, are very dark. They are divided into a “living” and a “sleeping” area, each one having a fireplace, which is used for cooking.

The Datoga women wear beautiful jewelry, have distinctive marks around their eyes and wear large ear-rings.

Depending on the area of Tanzania you drive through, and the time of the year, water can be a problem for the villagers. Often, they will need to dig for water and then fill large crates, which are hauled back to their village by donkeys. This is hard work, usually done by women:

Wherever you go, there are little businesses – restaurants, stands selling all kinds of things, and of course, innumerable markets. The atmosphere is always joyous, there is little haggling and people have time for everything. Supermarkets or signs of a more fast-paced environment, are practically non-existent.

We stayed in four hotels on mainland Tanzania. They were very different from each other and we liked them all, for different reasons.

Gibb’s Farm is set amidst lush vegetation. Originally a coffee plantation established by a British family in colonial times, it’s now a hotel with about twenty rooms. The views are beautiful (not a building in sight), the rooms very spacious and the swimming pool an absolute delight. As elsewhere, the food was delicious, almost entirely based on products from their own garden.

One afternoon, we accompanied a local Maasai, who showed us the many medicinal plants you find on Gibbs Farm and the surrounding area. He also showed us the area where elephants scrape the surface of rocks that are rich in magnesium, which they subsequently eat.

The Ziwanin Lodge on Lake Eyasi offers stunning views of the sunset. The vegetation is much more arid than at Gibb’s Farm, even though these hotels are only an hour or so apart. The architecture is very distinctive, with spacious rooms in a style reminiscent of Arabia. As elsewhere, the food was sumptuous.

Overlooking the Ngorongoro Crater, the Crater Lodge from the group &Beyond was a dream. The architecture is very distinctive and the views are just spellbinding. There are no fences on the property, so at night it’s not uncommon to bump into a buffalo or a leopard on your way back to your room from the central building. We only stayed here for one night, but had wished we had stayed longer. The sound of the birds in the morning and the views from our room are unforgettable.

The Four Seasons is on Serengeti National Park. When you are on the balcony of your room (or by the swimming pool), you feel part of this immense plain (Serengeti in Swahili means “endless plains”) and the peace you feel, especially in the evening is just magical. The hotel itself is much bigger than the others we stayed in, and it feels more “institutional”, but it’s still a great place, serving excellent meals.

One of then things not to miss when you visit mainland Tanzania, is a balloon flight. We hesitated, because it’s expensive and you need to get up at 4.30 am. But it was really worthwhile. You see the animals from a completely different perspective, you can see the paths they take and how the different animal groups move together. The colours in the early morning are beautiful and we were impressed by the peaceful environment. Finally, the champagne breakfast in the middle of nowhere was just magical.

One of the most remarkable aspects of our travel through Tanzania were the flights we took. Mostly, we flew in 12-seater planes. The ticket always indicated the departing and arriving airport, but often the plane would stop at additional airstrips. When asked, the pilot would explain that he had received a message from this or that control towes, asking if he could carry additional passengers. If there was room, he stopped and picked people up. It felt like we were in a school bus.

Our plane flights felt like travel in another time. You just walked onto the plane and sat wherever you felt like. Mostly, we sat behind the pilot, but on one occasion I sat on the copilot seat. The pilot suggested that I wear the copilot earphones, so we could chat and I could hear what the control tower was saying to him. I learned a lot about air bumps and the pilot told me hilarious stories about emergency landings and special rescue operations he had been involved in. At one point I asked him whether he had special instructions for me, in the (I hoped unlikely) case of him becoming suddenly incapacitated. He thought for a while, then said: “Yes, pray!”.

Our trip through mainland Tanzania was so memorable in large part because of the two guides we had, Onesmo and Omolo. Onesmo is the owner of East African Voyage, the agency we used to organise our trip. Omolo, who we rapidly named “Professor Omolo” after he displayed unparallel knowledge about wildlife, also acted as driver. “Dr. Onesmo” was instrumental in allowing us to understand the people, customs and political context in Tanzania. This was essential for us to understand what we were seeing and experiencing.

Importantly, our two leaders were hilarious. Their stories were incredible. The Professor told us about his many travels back home (he comes from the Luo tribe in northern Tanzania, but lives in Arusha) in order to secure an appropriate wife. How his family and friends helped (or didn’t). How he finally met the lady who is now his wife by a well, and proposed to her 5 minutes after they had met. And how it took another year and haggling with her father about the dowry before she became his wife. They now have two children and are, by what we could tell, a radiant and very happy family. To our question: ‘But how could you decide in 5 minutes?’ he answered, with a big smile: ‘Intuition’. And anyway, he added, ‘How long did it take you, Pedro, to figure out that Dana was right for you?’ I had to admit that it didn’t take me much longer than 5 minutes.

On another occasion, the Professor, whose Luo origins means that he and his wife have particularly dark skin, said to us. ‘You know, in my family we encourage everyone to smile a lot. We tell the children that if they don’t, Thea frétât might not be seen!’

Dr. Onesmo related to us his first trip to the US. How he had fantasized about being picked up in a convertible car at JFK Airport in New York. Instead, no one showed up and he had to take the subway. He got completely lost in New York City, with no money and no number to call. He finally made it to upstate New York, where he was expected as wildlife tutor in what turned out to be a nudist summer camp. This was only one of many of Onesmo’s unforgettable stories.

The first night we arrived in Tanzania, we stayed at Onesmo’s and were touched by his care for two young women (only one of them was a family member), who lived at his home and who, for a variety of reasons, had no other place to stay. We were also surprised by the “small breakfast” we were served before leaving in the early hours of the morning:

Above all, our two companions were intensely human. They were warm, alert, sensed what was right for us and discussed travel options at each stage. This allowed us to make the most of the time we were on the safari portion of our trip. We are intensely grateful to have them had with us for eight days.

During the Zanzibar portion of our trip, we visited the islands of Unguja and Pemba. After being a Portuguese and Omani colony, for most of the XXth century, Zanzibar was a British Protectorate. It was only in 1963 that it became independent, but only for a month, until it was merged with mainland Tanganyka into what is now Tan (for Tanganyka) Zan (for Zanzibar) nia.

Unguja’s capital, Stonetown, was very active in the slave trade until the very end of the XIXth century, and also a major hub for spices and ivory. Today, it is very much a run down place, but still, when you’re at the central market, you feel the intensity of what was, in former times, one of the most important trading towns in the Indian Ocean.

Farid, our guide, was gay, not an easy situation in what is an island that is 95% Muslim. What made it worse: his father had been an Imam. We asked him about the gay community and about growing up on Unguja. ‘Well’, he said, ‘I think that my father somehow understood. I was not obliged to marry. And anyway, here in Zanzibar, so long as you’re discreet, you can do whatever you like, everyone sleeps with everyone’. We didn’t learn much about the history of Zanzibar with our guide, but the rest of his stories (or what we could understand of them, his English was not very good) were just great.

Apart from an afternoon in Stonetown, we practiced farniente very intensely at our beautiful hotel, the Zuri, about one hour to the north, on Kendwa. Every day, we took long walks on the endlessly long beach. The evening meal was usually preceded by a lengthy apéritif on the beach.

We quickly fell in love with Zanzibarian food. It’s a mixture of African, Indian and Arabic cuisine, and it’s easy to prepare. In Stonetown we bought a few spices, with the help of the hotel staff collected a few additional fresh herbs, and then were fortunate enough that the Zuri chef had time to teach us. We were surprised at the variety and speed of preparation: the chef put together eight dishes in less than two hours. Several of these we’ve already successfully recreated in Geneva.

On the beach, we befriended the Maasai who acted as guards, tourist-guides and sellers of souvenirs. I made them laugh with the few words of Maasai language I had learned on the mainland. One day I said to them: ‘I will give you USD 10.- if you can figure out in what country I was born’. Now I really had their interest. Three of them tried their best: Italy, Spain, Germany, etc. were suggested in rapid succession. I shook my head.

When I went back to the hotel that evening, they hadn’t yet guessed. When I arrived on the beach the following day, five young Maasai were waving at me from a distance. ‘We got it’, they said, ‘you come from Serbia!’. ‘No’, I said with a disappointed face. ‘It must be Russia, then’, said another. By the end of the second day, no one had guessed.

On day three, they came accompanied by a security guard, who had a walkie-talkie. The team now included a lady sitting at the reception, who had access to the internet. ‘Ukraine, Belarus, Belgium, Canada, US’. I left the beach that evening and no one had yet guessed.

On day four, I decided to help out a bit. ‘Watch me’, I said:

Another few trials and finally, finally, I heard ‘Argentina’. I gave the winning Maasai his $ 10.-From then on, and until the end of our stay, wherever I went on the beach I would invariably hear someone shouting at me: ‘Messi!’, to which I would respond: ‘Agüero!’. A little farther down the beach I would hear: ‘Maradona!’. ‘Di Maria!’, I would respond. Even the service personnel in the hotel restaurant welcomed me with ‘Argentina, Argentina!’ every time I showed up for meals.

After the excitement on Unguja, Pemba Island was a completely calm experience. It’s a large island, 67 km long and 22 km wide, but it has only 5 hotels. In the time when we were there, three were closed and at the Aiyana, where we stayed, only one other room as occupied. So it very much felt like the island was all for ourselves.

Being on Pemba was like being on an island from another time. In the morning you would see the cattle roam down the beach. Children came to talk to us frequently and there were plenty of hours when nothing, absolutely nothing happened. The hotel staff felt more like friends, and I would play the African game bao with them in the afternoon (it’s a very interesting strategic game, easy to learn but very difficult to master).

On most of the beaches we explored, we met no one. But on one occasion, we bumped into a group of young Pembese. It didn’t take long before we were invited to dance.

The Aiyana manager strongly urged us to visit by boat an island that exists only a few hours each day, when the tide is at its lowest. We hesitated. What to do on such an island? Luckily we went. It turned out to be an unforgettable experience.

Depending on the time of the year and the size of the tides (and the time of the day or night when the tide is at its lowest), this elusive island is bigger or smaller. When we were there, conveniently, it was accessible in the middle of the day, and it was quite large. At least large enough to have lunch and to watch, in astonishment, the surrounding sea. We were all alone! It reminded me of the wonderful stories of King Babar, the little elephant, that my grandmother used to read to me as a child.

This report would not be complete without a heartfelt and enormous thank you to Kennedy Mmasi, the initiator and spiritual guide of our travels in Tanzania. Kennedy went to university with Nico Simko and one evening in 2020, while he was staying for a few months in Geneva, we invited him to dinner to our home. He told us about his home country, and it made us dream to visit it. It was Kennedy who got us in touch with Onesmo. It was he who insisted on us taking the balloon flight and it’s because of him that we visited Pemba. Thank you, dear Kennedy! Your country delivered what you promised. And so much more!