Braila, a city in eastern Romania, offers a stark reminder of how towns rise and fall, at the mercy of politics and politicians.

My family lived in Braila in the middle of the XIXth century and I was curious to find out more about this town, which is only a short distance away from Craiova, where Dana Evelyn and her family originate from.

Our visit gave us a lot ot think about, much more than about family history.

From the middle of the XIVth century onwards, until it was conquered by the Turks in 1540, Braila was a prosperous commercial town. As many European settlements at the time, its wealth came from a favourable location on the banks of a big river, in this case the Danube, which allowed for the easy transport of goods and people.

Then, from 1540 until 1828, Braila’s fortunes changed. During this time, it was ruled by the Turks, and Braila’s role became a military one. Because the town was located on the northern tip of the Ottoman Empire and happened to have a little hill, from which the surrounding area could easily be scouted, the Ottoman rulers in Istanbul designated its role as a defensive, not a commerical one. They built a large military fort on the hill and stationed an army there.

With its trading possibilities sharply reduced, Braila’s commercial activities were severely curtailed. Not surprisingly, its population declined, with only about 3’000 people living in the town in the 1820’s.

In 1828, the Russians defeated the Ottomans and as part of the ensuing peace treaty, Braila was reintegrated into the Kingdom of Wallachia. Importantly, the town was granted “full liberty of commerce”, meaning that it was able to trade with any nation.

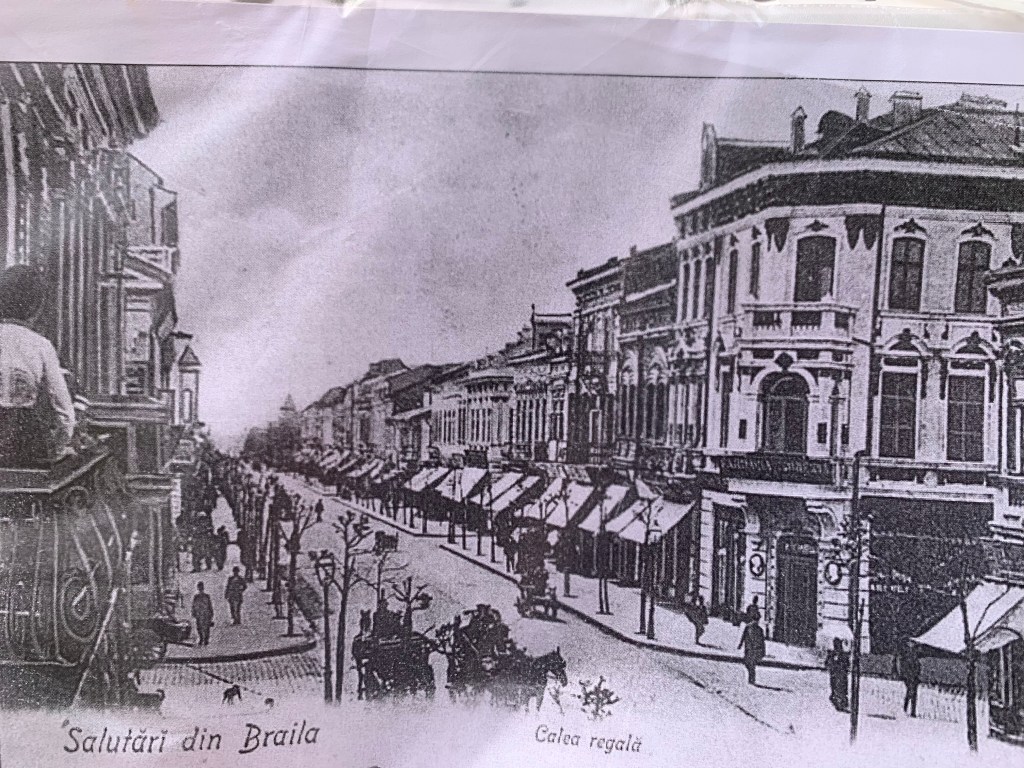

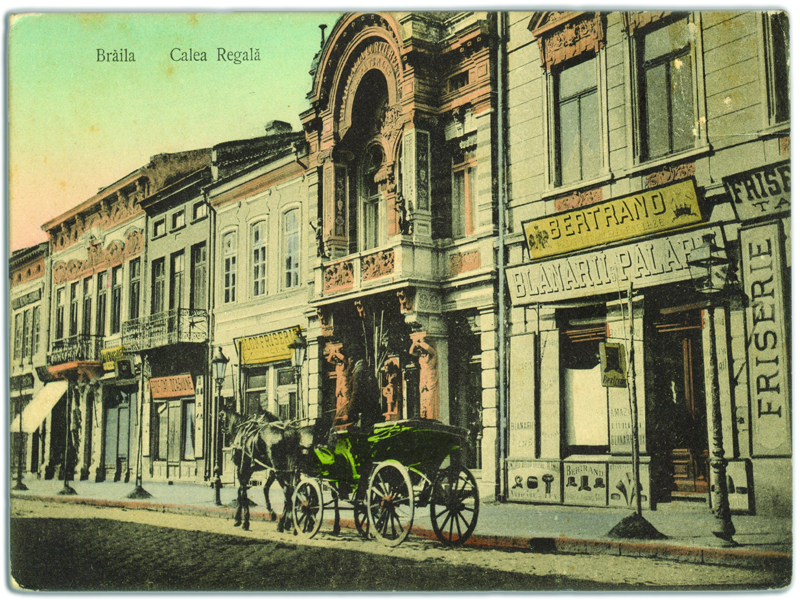

Immediately thereafter, Braila’s military citadel was dismantled and in its place a new, beautiful city was built, with concentric roads and lovely boulevards springing from an elegantly designed centre square.

With the promise of freedom of enterprise, and an attractive new architectural layout, Braila became a magnet for immigration. In 1834, only six years after the defeat of the Turks, Braila’s population had already doubled. Only nine years later, in 1843, the city’s population had again more than doubled and now stood at 14’000. By the end of the XIXth century, Braila counted 58’000 inhabitants and in 1939, on the eve of World War II, its population had again almost doubled to 99’000 inhabitants.

Braila’s prosperity in the period between 1840 to 1950 was strongly related to the grain trade. During the second half of the XIXth century, industrialisation throughout Europe and the mechanisation of agriculture meant that the fertile and large plains of Oltenia and Wallachia produced cereals in ever increasing quantities and exported them through Braila to a hungry, growing and rapidly urbanising European population. Industry developed too, and by 1900, Braila was also one of the most industrialised cities in Romania.

The first foreigners to arrive were Greeks and Italians, soon followed by Jews and Lipovan Russians. By 1932, almost 20% of the city’s residents were of Jewish origin.

The new residents built beautiful mansions, many of which have survived to this day and are a testimony of the refinement and wealth of the town.

Braila quickly became a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic community, which attracted not only businessmen, but a wealth of artists and intellectuals, transforming the town into a vibrant and exciting cultural centre, where multiple languages were spoken and a criss-cross of European cultures not only coexisted peacefully, but fed on each other. The entire population could afford to dine at restaurants, which were always full and catered to the many culinary tastes of its very diverse ethnic groups.

The various religious groups built ever more impressive places of worship for their communities, many of which have survived to this day.

Think of London around 2010, with its plethora of exciting and trendy shops, its fusion restaurants, its many ethnic groups and its large variety of social and cultural events, that’s what Braila was like for over a century, from the 1830’s till the late 1940’s.

Among the many Jews who settled in the city was my great-great grandfather Moritz Ellmann. He claims to have been born in Braila in 1833, but this is unlikely. There are no records of his birth there and the city’s 1838 census does not show any Ellmann residing in the town.

What is sure is that Moritz and his wife Amalia Deutsch, also a Jew, lived in Braila between 1864 (when my great-grandfather Samuel was born) and 1868, the birthdate of their second son Marcu (Max). The Ellmanns again resided in Braila in 1876, where Adolf (Dolfi) was born. In between, they lived in Vienna, where two more children would be born (Isidor in 1870 and Eduard in 1872). They definitively left for Vienna in the late 1870’s, where their daughter Caroline (Line) would be born in 1881.

Like many other Ashkenazi Jews, the Ellmanns probably migrated from Galicia (a territory which is now split between Poland and the Ukraine) to Braila, attracted not only by business prospects, but also by freedom from anti-semitic perspecution, so common at the time in central Europe.

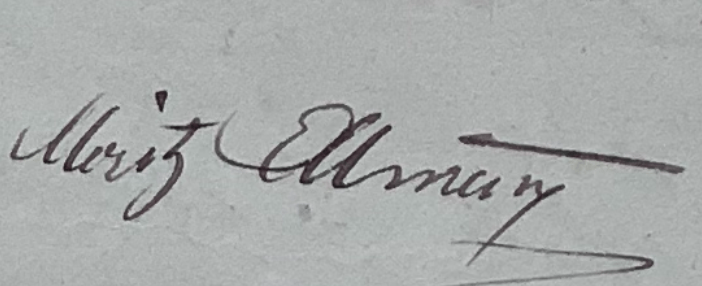

Moritz was a tailor, a typical occupation for Jews at the time (80% of Jews living in Galicia at the end of the XVIIIth century cite their profession as tailors). Until the arrival of prêt à porter clothing in the XXth century, tailors did a lot more than repair or adjust clothes, they set trends and the better-known ones, were the centres of fashion of the time.

There is every reason to believe that Moritz was an up-market and trendy tailor. In 1876 he lived at 4, Bucuresti St (later called Regala St), the very best location for a high-end tailor, right at the beginning of the most fashionable avenue in Braila (think of the Avenue des Champs Elysées in Paris, that’s where Moritz resided and had his atélier).

Unlike in other European cities at the time, Jews were not subject to restrictions and could live anywhere they pleased in Braila. Accordingly, the Jewish families were spread across the town and their children grew up in a truly multicultural environment. Ethnicity was simply not an issue, and according to the reports of Jews living in Braila at the time, their children would grow up playing with their Greek, Romanian, Russian or Bulgarian neighbours.

Everyone in Braila spoke several languages. The fact that the town was so open to international commerce meant that the people of Braila lived in a relatively small, but a highly sophisticated and cosmpolitan environment.

The Jews who initially settled in Braila were artisans, like my ancestor Moritz. Those that followed them were grain traders and bankers. Josef Ellmann, most probably a member of our family, appears in the register the city in 1901. He was a banker, and prominent enough to have become, in 1903, one of the founders of the Jewish Colonial Trust, the financial institution of Theodor Herzl’s Zionist movement, the offspring of which is today’s Bank Leumi.

The Ellmanns’ back & forth between Vienna and Braila between 1870 and 1880 is most probably related to Moritz’s business activities. At the time, the two cities were within easy reach of each other through a network of comfortable steamships traveling up and down the Danube. It took no more than three days to reach each city and interesting contacts could be made among the passengers’ wealthy guests. Moritz most likely travelled extensively between the two towns, bringing the latest Viennese fashion to Braila.

We don’t have a photo of Moritz, but his elegant signature suggests that he is a refined man, as would be befitting to an up-market and worldly tailor.

Moritz’s sons Eduard and Dolfi would perpetuate the family tradition by setting up a business of silk manufacture in Vienna. By 1938, Eduard must have been wealthy enough to not only have escaped the Nazi annexation of Austria, but also to have lived for the next 35 years in England, until his death in 1973 at the age of 101, without having to work.

Surviving photos of Dolfi and Eduard Ellmann taken in Vienna in the 1920’s and 1930’s show them as worldly and very elegantly groomed.

So what happened to the cosmopolitan, wealthy and worldly Braila, a town celebrated by visitors and poets, out of which sprang such beautiful buildings and cultural events?

World War I created a short pause in the development of the city; in the period between the two World Wars, Braila continued to grow, both economically and culturally. World War II again cast a shadow, but it was not devastating. The community held together and the Jews, although ostrasized and put under severe restrictions, were not deported, and no Braila Jew was murdered during Antonescu’s pro-Nazi regime in the 1940’s.

The downfall of the city began with the instauration of the communist regime in Romania, starting in 1947. The Soviet-aligned Socialist Republic of Romania designated Braila as an “industrial” town. All stores disappeared in 1948. Romania’s borders to the West were closed, international trade was severely curtailed and it only took a few years before Braila became a dull, provincial town.

The multicultural nature of the city faded, because of the mass exodus of foreigners and Jews. Forced industrialisation and socialist “uniformisation” killed the city’s vibrant cultural spirit.

Today’s Braila feels like a ghost town. Some of the beautiful old buildings have been restored, buy many more have been abandoned and left to decay. The large avenues are still there, but few people walk down them.

On the Strada Regala, now called Mihai Eminescu, where Moritz Ellmann had his atélier, and which is reminiscent of Paris’s grand avenues, most shops are empty. Those that are open, are pawn shops or second-hand clothing stores.

The wonderful Hotel Pescarus, now has trees growing from its windows.

The only thriving business in Braila nowadays appears to be gaming outlets and casinos, of which you find dozens in the city.

So what can we learn from the demise of Braila? The lesson is that cities are like living beings, to prosper they need to be taken good care of. It’s not because today you live in a thriving, beautiful and exciting town, that the same will be true tomorrow.

It’s economic conditions and, more importantly, politics, that led to the changing fortunes of Braila, first in the 1830’s, when it rose from a sleepy border town to become a city of major importance, and then in the 1950’s, when its fortunes went into the other direction.

What should you remember? If you live in a city you love (for us, it’s Geneva), make sure that you elect the right people to office, those who have a long-term perspective of their mandate, those who treat the city with love and care, and who are willing to create the conditions of openness which will invite people to stay.

Migration was the key reason why Braila did so well for over a century. Politicians who close borders or who create other travel or residential restrictions, to preserve the “local culture”, in fact create the opposite of what they want, they strangle the life out of cities, they weaken the society that they say they are protecting. It’s true that politicians can’t do everyhing, but they can do a lot to create the right environment for beautiful and thriving urban spaces. So, for those of you who, like us, live in free and democratic societies, at the next election, think twice who you vote for!

Your research about Braila was thorough.I hope the next article will be about Craiova !

LikeLike

Fascinating and saddening at the same time, there are many lessons to be learned from the history of Braila. It’s amazing you found out so much about your family!

LikeLike

I love to see this kind of scholarship ; a charming and really interesting blend of what is personal and what is universal .

LikeLike