One of the reasons we moved to Thailand earlier this year, is because we wanted to know what it was like to live in a Buddhist country.

It has indeed been a hugely enriching experience. Buddhism is not only vibrant and present in Thailand’s over 40’000 active temples, it also permeates the daily life, culture and attitudes of the Thai people. You cannot understand Thailand unless you are familiar with the country’s Buddhist practices.

Buddhism is one of the world’s oldest and most influential religions, but as it spread 2’500 years ago from its origins in India across to Asia, it evolved into various currents that were shaped by local cultures, histories, and traditions. What makes Thai Buddhism special, particularly in comparison to its counterparts in neighboring countries like China and Japan?

At the core of Thai Buddhism is the Theravada tradition, often referred to as the “Teaching of the Elders.” This form of Buddhism is considered the oldest and most traditional, staying close to the original teachings of the Buddha and recorded in what is known as the Pali Canon (the oldest existing Buddhist writings, recorded in Pali, a language only spoken rarely today, but common in India in the Buddha’s time).

Theravada Buddhism emphasises personal responsibility, ethical conduct, and the pursuit of enlightenment (Nirvana) through meditation, moral discipline, and wisdom. In the Theravada conception of Buddhism, you become enlightened through your own merit and hard spiritual work. Monks are there to guide you, but it is through your personal effort that you will reach Nirvana.

In contrast, China, Japan, South Korea and Vietnam practice Mahayana Buddhism, which takes a broader approach. Mahayana, meaning “Great Vehicle,” emphasises the role of the Bodhisattva—an enlightened being who chooses to delay Nirvana, so as to help others achieve enlightenment. This school has led to the development of diverse branches such as Chan (Zen) and Pure Land Buddhism, particularly prominent in China and Japan. In the Mahayana tradition, the historical Buddha is considered one of many Buddhas, with some having lived before him and others, like Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future, coming after him.

In Thai Buddhist temples, the focus is predominantly on images of the Buddha, reflecting the Theravada emphasis on Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha.

However, in Chinese and Japanese Buddhist temples, the range of images you will see is much broader due to the influence of Mahayana Buddhism and the incorporation of local cultural elements. It’s what the great Japanologist Alex Kerr calls “a gorgeous firework of divinities”, very different from the single-minded focus of the Theravada school.

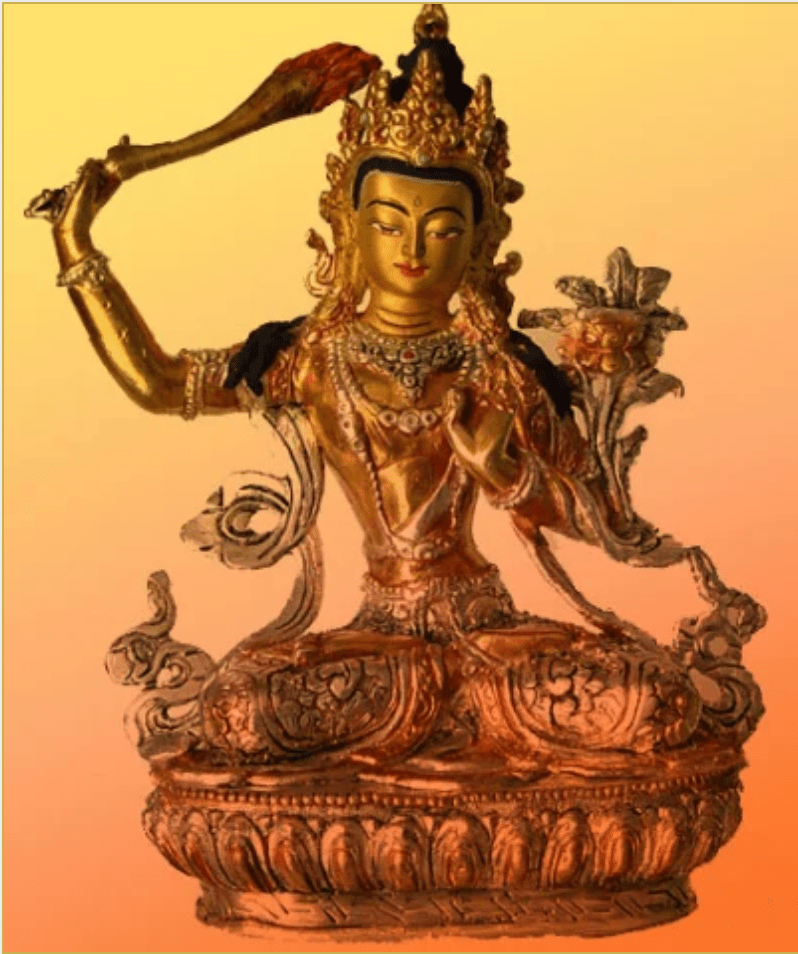

In Chinese temples, you might encounter, in addition to the historical Buddha, also images of Amitabha Buddha (the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life) and the Medicine Buddha (the Buddha associated with healing and medicine). In addition, you will also see a range of Bodhisattvas such as Guanyin (the Bodhisattva of Compassion), Manjushri (the Bodhisattva of Wisdom), and Ksitigarbha (the Bodhisattva of the Underworld). In addition, you are likely to also see Arhats (enlightened disciples of the Buddha), and Heavenly Kings (protective deities, each guarding one of the cardinal directions, often found at the entrance of temples).

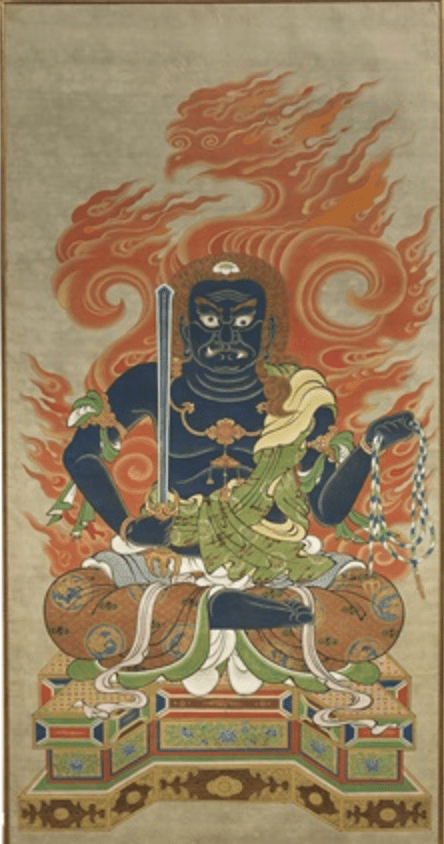

In Japanese Buddhist temples, you are likely to see, in addition to the historical and Amida Buddha, images of Bodhisattvas such as Kannon (representing compassion), Jizo (revered as the protector of children, travelers, and those who are suffering), and Fugen (the Bodhisattva associated with practice and meditation). Other deities and figures you might find are Arhats (these enlightened disciples of the Buddha are often depicted in Zen temples, symbolising the ideal of reaching Nirvana), Fudo Myoo (a wrathful deity associated with esoteric Buddhism) and Seven Lucky Gods (although not purely Buddhist, these figures are commonly found in Japanese temples and shrines, representing various aspects of good fortune and protection).

In Thailand, the teachings focus on the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, which outline the nature of suffering, its causes, and the path to enlightenment. This scriptural’s emphasis on practical wisdom and ethical living, is a hallmark of Thai Buddhism.

By contrast, the Mahayana tradition works with a vast and diverse body of religious scriptures, often written in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan, including a wide range of sutras, treatises, and commentaries. Unlike the Pali Canon used in Thailand and other Theravada countries, which as we have seen is believed to have been compiled shortly after the Buddha’s death, the Mahayana sutras emerged later and reflect the evolving spiritual and philosophical needs of Buddhist communities as Buddhism spread across Asia. Some of Mahayana writings date from as recently as the VIth century AD (the historical Buddha lived more than 1’000 years earlier).

One of the most distinctive aspects of Thai Buddhism is the central role of monasticism. The Sangha, or community of monks, is highly respected in Thai society. Monks are seen not only as religious leaders but also as moral guides, educators, and community figures. Their presence is deeply felt in daily life, from the early morning alms rounds, where they collect food offerings (monks have no money, they live off gifts), to their participation in community events and rituals.

A unique tradition in Thailand is the practice of temporary ordination. Many young Thai men, often before marriage, spend a period of time as monks. This temporary ordination is seen as a rite of passage and a way to make merit for oneself and one’s family. This tradition underscores the importance of monasticism in Thai culture, as it allows individuals to experience monastic life and contribute to the spiritual welfare of their families.

Merit-making, or tam bun in Thai, is a central practice in Thai Buddhism. It is believed that performing good deeds, such as giving alms to monks, donating to temples, or participating in religious ceremonies, generates merit that will positively influence one’s current life and future rebirths. The concept of merit is deeply ingrained in the Thai Buddhist worldview and drives much of the religious activity in the country. This explains why, wherever you go in Thailand, the temples are so immaculately and beautifully kept. Many temples are still being built nowadays.

Merit-making is not only a personal endeavor but also a communal one. Festivals, temple fairs, and public ceremonies are often centered around opportunities to make merit. These events are lively, communal affairs where entire communities come together to support the local temple, engage in rituals, and celebrate their shared faith.

Thai Buddhism is uniquely characterized by its integration with local animist beliefs and practices. While the teachings of the Buddha form the core of religious practice, many Thais also engage in rituals that honor local spirits and deities. This syncretism is evident in the widespread practice of maintaining spirit houses (san phra phum), where offerings are made to the spirits of the land. It is believed that by honoring these spirits, one can ensure protection and prosperity. In addition, quite a few Thai temples include Hinduist gods and a whole range of other gods.

This blending of Buddhism with animism, as well as the inclusion of other non-Buddhist deities, creates a unique spiritual landscape where traditional Buddhist practices coexist with local customs. For example, during major life events such as weddings, funerals, and the Thai New Year (Songkran), rituals often incorporate both Buddhist and animist elements, reflecting the harmonious integration of these beliefs.

The veneration of Buddha statues and amulets is another distinctive feature of Thai Buddhism. Statues of the historical Buddha are ubiquitous in Thailand, found in homes, temples, public spaces, and even in vehicles. These statues are not merely decorative; they are objects of deep reverence, serving as focal points for prayer, meditation, and offerings.

Amulets, or Phra Khruang, hold a special place in Thai Buddhism. These small, often intricately designed objects are believed to offer protection, bring good luck, and enhance spiritual power. Many Thais wear amulets as part of their daily lives, and there is a thriving culture of amulet collection and veneration. There is even a large amulet market in central Bangkok. The belief in the protective and spiritual power of these amulets is deeply rooted in Thai culture, making them an integral part of everyday life.

In Thailand, wats (temples) serve as more than just places of worship; they are the heart of community life. Temples are where people gather for religious ceremonies, festivals, and social events. They provide a space for meditation, learning, and communal activities, playing a central role in the social and spiritual life of Thai communities.

The architecture of Thai wats is distinctive, with ornate roofs, golden stupas, and intricate murals depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha. These temples are not only religious centers but also cultural landmarks, reflecting the rich artistic heritage of Thailand. Many wats also operate schools and charitable services, further cementing their role as essential institutions in Thai society.

Another unique aspect of Thai Buddhism is its close relationship with the Thai monarchy. The King of Thailand is traditionally seen as a Dharmaraja, or a righteous king, who upholds and protects Buddhism. This relationship between the monarchy and Buddhism has historical roots and continues to play a significant role in Thai national identity. Buddhist thinking is also at the heart of the Thai legal system, where the belief is that laws are not man-made, but pre-ordained, eternal and should reflect cosmic harmony.

The King’s support for Buddhism is evident in state ceremonies, where Buddhist rituals are prominently featured. This connection reinforces the idea of Buddhism as not just a personal faith but a cornerstone of the nation’s cultural and spiritual identity.

In addition, many Thai homes include an area where Buddha statues are kept. This area is reserved for daily prayers and meditation.

So if you visit Thailand and, as most visitors do, you immediately feel the warmth, kindness and helpfulness of the population, remember that it isn’t by chance, a lot of it has to do with Thailand’s celebration and day-to-day application of Buddhist Theravada values.