New Zealand is the last of the world’s large landmasses to have been colonised by humans.

It is only in 1250-1300 AD that Polynesians from the area that is today Tahiti, the Cook Islands and the Marquesas, arrived in what is now New Zealand, a land which they called Aotearoa (Land of the Long White Cloud).

Why did Australians not colonise New Zealand, which is geographically much closer to Australia than Polynesia? After all, humans had reached Australia about 45’000 years before Homo sapiens began to colonise Polynesia in 1000 BC, let alone reach New Zealand more than 20 centuries later.

The answer is that Australians did not have the technological capabilities or the seafaring culture that Polynesians had, who developed large, ocean-going canoes (waka hourua) that could travel vast distances across the Pacific. These double-hulled canoes were capable of carrying dozens of people along with food, water, and animals over long periods of time.

Waka hourua had two hulls connected by a platform. This design provided stability and buoyancy during long-distance ocean navigation. The twin hulls made the canoe more resistant to capsizing in rough seas, which was essential for voyaging over long distances in the open Pacific Ocean. Polynesian navigators used sophisticated knowledge of the stars, ocean currents, winds, and bird migration patterns to guide them across the open ocean.

By the time Polynesians settled in Aotearoa, they had already colonized most of the Pacific, from Hawaii in the north, to Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in the east, and Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa in the west.

Polynesian societies valued the discovery of new lands and the establishment of new settlements. This exploratory spirit was deeply ingrained in their culture, which involved the deliberate transplantation of plants and animals (such as pigs, dogs, and chickens) to new islands for long-term settlement. Settlers arrived with their families, equipped with tools and equipment to use in their new homes.

Their expansion was often driven by population pressures, resource limitations, and sometimes internal conflicts, which led them to seek new lands where they could establish thriving communities.

The fertile lands of New Zealand, with its forests, rivers, and potential for agriculture, were a tempting destination, but resettlement here required substantial adaptation, since the climate is much colder than in Polynesia. This explains why New Zealand was colonised so late.

By contrast, indigenous Australians had a fundamentally different way of life, one that was largely based on hunter-gatherer methods, with deep spiritual and practical ties to their local environments. There was less emphasis on long-distance exploration or settlement in distant lands. Australia’s vast and varied landscape provided ample resources for indigenous Australians, so there was less pressure to move beyond the continent in search of new territories.

When the Polynesians arrived in New Zealand, they brought with them sweet potatoes, taro, yam and gourd, which they successfully adapted to the cooler New Zealand climate. They also introduced pigs, chickens and dogs, which would alter the local environment in fundamental ways.

Whereas taro, yam and gourd had been staples in the Pacific homeland of the Polynesians for thousands of years, sweet potatoes (which would become the most important food source for the Maoris) originate from the tropical regions of Central and South America. The exact origin is believed to be near present-day Mexico. Sweet potatoes were domesticated by the indigenous peoples of the Americas more than 5,000 years ago and gradually spread across the continent, becoming a staple food crop.

How did sweet potatoes reach the Polynesians? Apparently, Polynesians reached South America between 1000 and 1100 AD, about 300 years before the arrival of Europeans. The sweet potato arrived in Polynesia around this time, as archaeological evidence shows its presence in the Cook and Society Islands by 1200 CE.

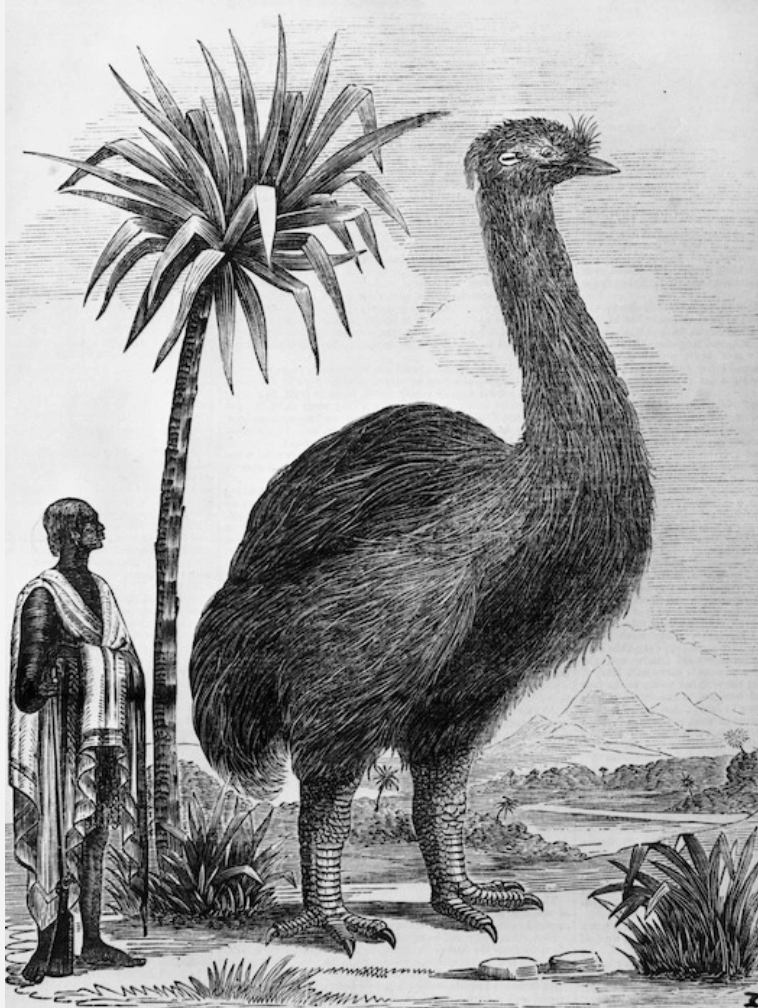

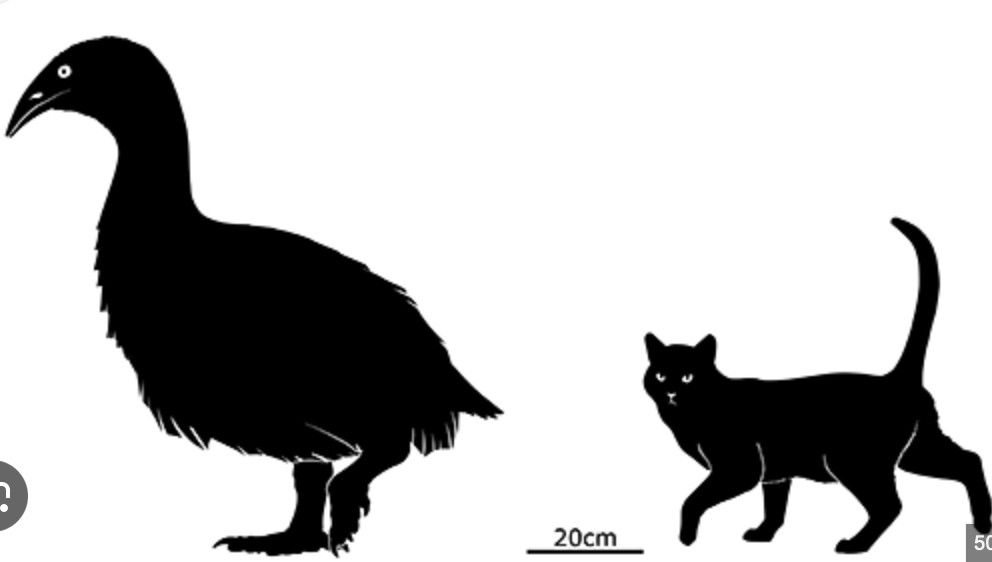

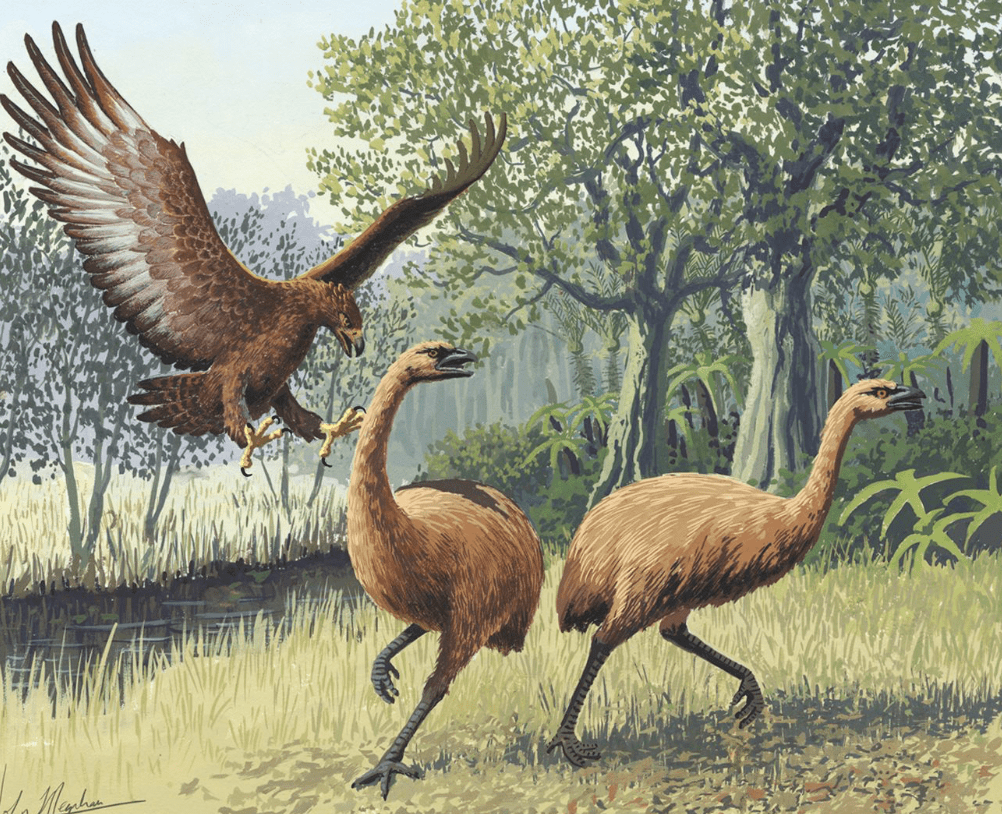

Polynesian settlers introduced sweet potatoes (kumara) to New Zealand when they arrived around (1250–1300 AB). In addition to the staples they carried with them, upon arrival the Maoris encountered a range of native animal species that were unique to the islands. Many of these animals had evolved in isolation and had no natural predators before human arrival. As a result, several species, particularly birds, were rapidly hunted to extinction by the Māori. The most notable of these were large, flightless birds, which became a primary sources of food for the early Māori (moa, large native swans, geese and Adzebills).

As a consequence of the disappearance of these birds, other species, like the Haast Eagle (the largest eagle ever to have existed) died out too.

In addition to hunting local species, the Maori introduction of dogs and rats also contributed to the extinction of native species. Rats preyed on the eggs and chicks of many ground-nesting birds, while dogs helped humans hunt and likely killed birds themselves.

The Maori also cleared large areas of New Zealand’s forests for agriculture, which further reduced the available habitat for the local birds.

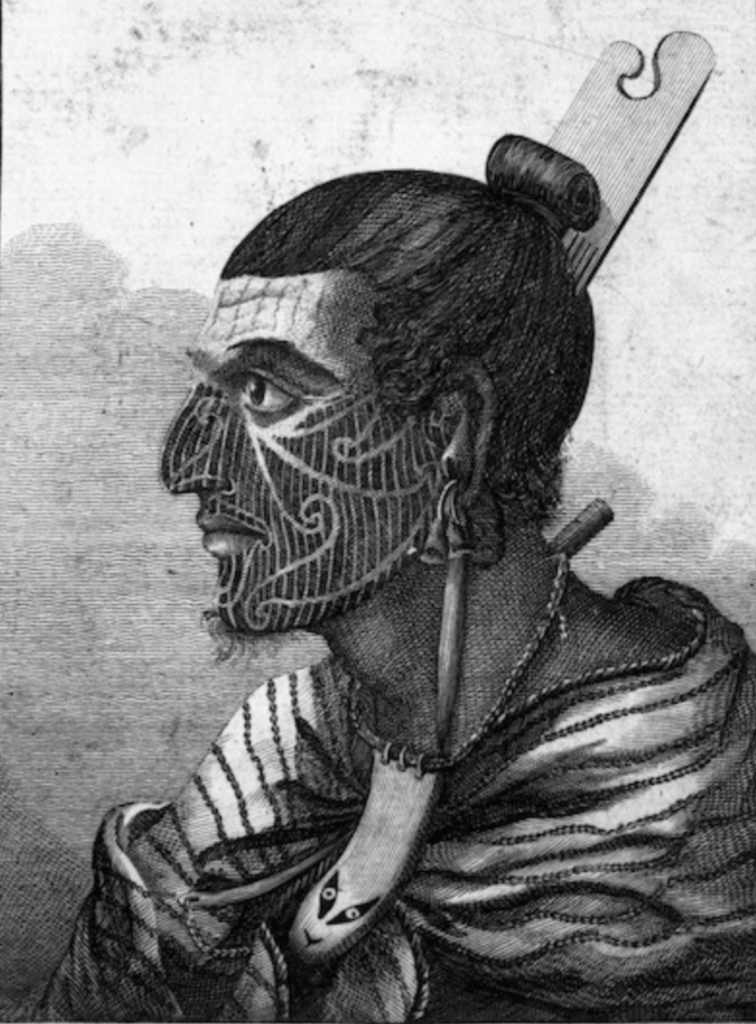

Over time, the Maoris began to practice more sustainable agricultural practices and developed a deeply spiritual culture, based on the worship of their ancestors and a belief in the interconnectedness of all life. The descendants of the original Maori settlers spread across both the North and South Islands of New Zealand, establishing different iwi (tribes) and hapu (sub-tribes) that still exist today. These tribes were often at war with each other. This disunity would prove fateful in the subsequent period of European colonisation.

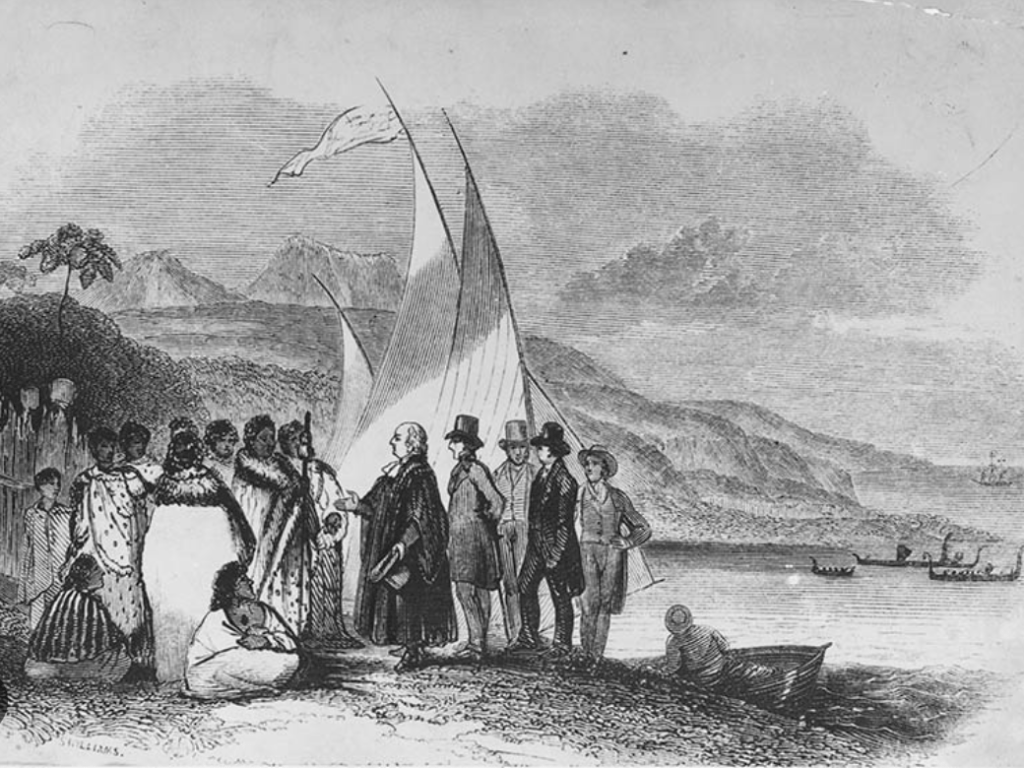

The first European to reach New Zealand was Abel Tasman in 1642, a Dutchman who was sent by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to explore the southern waters of the Pacific Ocean in search of new trade routes and lands.

Tasman reached what is now called Golden Bay in the northern part of the South Island, but his encounter with the Maoris was not fortunate. The locals treated the newcomers with hostility, killing several of them. Tasman continued his voyage but did not set foot on the newly discovered islands, which he observed from a distance and named Nieuw Zeeland (after the Dutch province of Zeeland), which eventually became New Zealand in English.

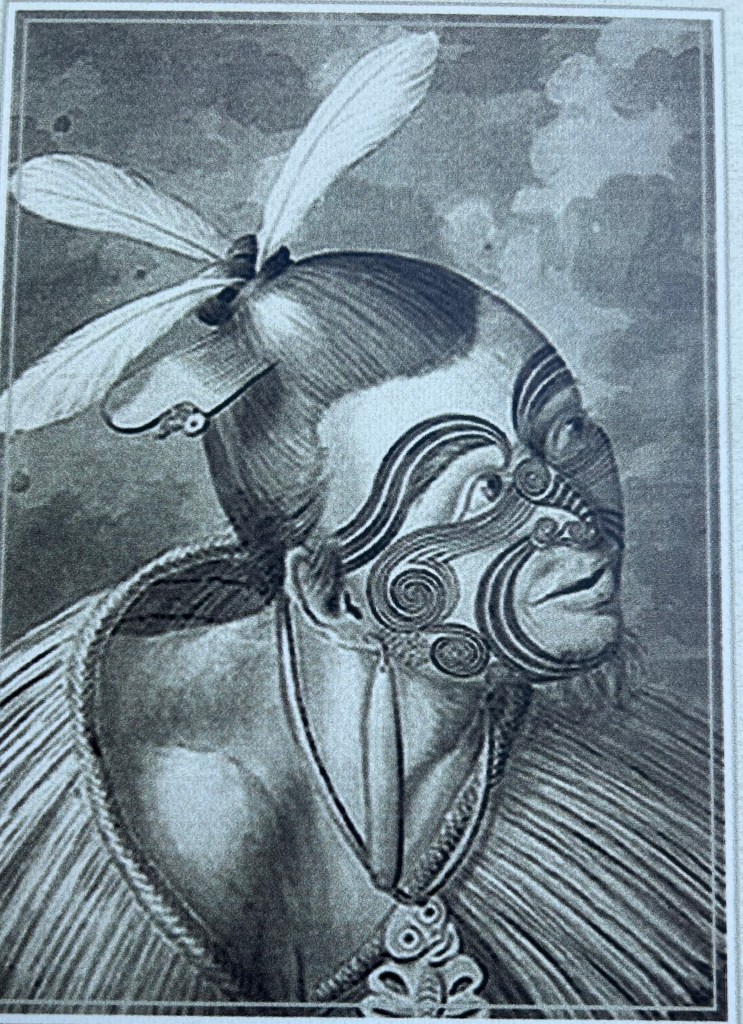

Thereafter, no Europeans visited New Zealand for over a century. The next explorer to reach New Zealand was James Cook in 1769. He took a more diplomatic approach than Tasman and succeeded in creating a friendly relationship with the Maori. Cook, who got to know the Maori well after a series of trips, described them as a warrior people but also as highly organized, with a complex social structure and advanced navigational and agricultural knowledge. Joseph Banks, who accompanied Cook, recorded admiration for the Maori, particularly their physical prowess and craftsmanship. European XVIIIth century descriptions of the Māori regularly portray them as exotic, brave, and untamed, but with qualities that Europeans could admire.

Trade rapidly increased. Only a few years after the arrival of Cook, the Maori began to regularly visit neighboring Australia. As Brian Sweeney notes: “In 1774, an Australian newspaper commented on how ‘extremely shrewd in making bargains’ they had become and by 1833, their image was summed up by one local as ‘industrious, intelligent, bold, and enterprising’ ”.

The Maoris embraced the opportunities that contact with the European newcomers provided and began to explore the ‘new world’ which was opening to them. As Sweeney notes: “During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Maori became ‘chiefs of industry’ and travelled the world. Their forays began on American and European vessels in return for income and passage to foreign places. Some became shipmates and officers while others chose to settle permanently overseas. However, most returned home and brought with them a wealth of overseas experience which helped to establish a diverse range of Maori-owned industries. These industries included flour mills, shipping lines, market gardens, tree milling, gum mining, and as a precursor to today’s staple – the nation’s first commercial dairy farm. In the absence of any formal laws or government, economic and social relations between the two races was exceptional and for the most part, they lived together in harmony as they forged ahead with a distinctly New Zealand identity.”

However, trade with the Europeans also included firearms, with disastrous consequences. The belicose Maori tribes subsequently killed each other with such savagery that over 50% died in the early decades of the 19th century.

What were the Maoris fighting about? In Europe, wars have always been about territorial or economic gain. The Maoris generally did not fight for land or for resources. Their wars were primarily about honour. Maori society was heavily governed by tapu (sacred laws and prohibitions). A breach of tapu, such as desecrating a sacred site, violating a chief’s mana (spiritual power), or disrespecting ancestral remains, could lead to warfare. Defending or restoring tapu often became a motive for conflict, as failing to address such breaches could diminish a tribe’s spiritual authority.

While the Maoris were busy killing each other, Europeans started to settle in a land and a society that (at least initially) welcomed them. Christian missionaries were invited to settle in New Zealand and wrote admiringly of the Maori oral traditions, craftsmanship, and societal organization. As missionaries worked to convert the Maori, they also became intermediaries between Maori and European settlers, helping to spread European ideas of governance, trade, and diplomacy. In a time when most Europeans looked down on aboriginal peoples, believing them to be inferior humans, the missionaries portrayed the locals as intelligent and “capable of adaptation to European ways of life”.

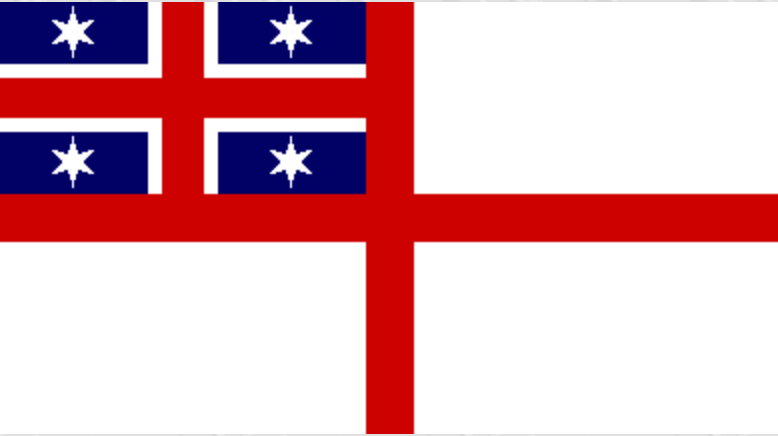

As more and more Europeans arrived, the Maori chiefs got increasingly concerned. In 1835 they finally left their differences apart, got together and took the bold step of creating their own flag and declaring independence.

Surprisingly, the British King rapidly accepted the Maori’s declaration of independence and acceded to their request for “protection”. He was strongly motivated to be conciliatory towards the Maoris and eager to engage with them, since the French had at this time also annexation intentions for New Zealand (indeed, only a few years later, the French established a short-lived colony in what is now the area of Akaroa in the South Island).

In 1840, only a few years after the declaration of independence, the Maoris were tricked into to signing the Treaty of Waitangi, a document ambiguously written (and whose versions in English and Maori languages differed), leading to a subsequent long series of misunderstandings and finally war between the British and the Maoris between 1860 and 1880, with disastrous consequences for the latter.

Many of the Paheka (white European) and Maori misunderstandings have to do with fundamentally different views of land ownership. For the Maori, a specific tribal group belonged to the whenua (land) and had responsibilities towards it (for Maoris, it is not humans that own the land, it’s the land that owns humans). For the British, land was just a commodity that individuals could own and trade endlessly. Accordingly, Maoris were brutally offended by Europeans settling on a piece of land and claiming it for themselves, when this land had, many generations ago, claimed a certain tribe (and other living creatures) for itself. The European attitude was seen by the Maoris as a great offense towards Papatuanuku, the Earth Mother.

In practice, the Treaty of Waitangi transformed New Zealand into a British colony, a far cry from what the Maoris had intended a few years earlier with their 1835 Declaration of Independence.

The Waitangi Treaty opened the door to a massive relocation of (mostly British) Europeans to New Zealand. In 1840, the population of Maoris was about 56’000, (down from about 120’000 in 1770, when Europeans first arrived), the consequence of wars and disease, while Europeans were no more than 2’000 to 3’000.

By 1900, the Māori population had fallen further to around 42,000, a decline largely due to continued exposure to diseases, land loss, and the disruption of traditional Māori society and economy. Meanwhile, the European population surged enormously, due primarily to British immigration, encouraged by government policies offering land and opportunities. The discovery of gold in Otago (1861) and Westland (1865) gave an additional boost to migration, bringing fortune seekers from Europe, North America, and Australia. The gold rush boosted the early colonial economy, fueling infrastructure development and trade. By 1900, the European settlers (called Paheka) had grown to over 770,000 and completely dominated New Zealand’s society.

By 1926, New Zealand’s total population had reached over 1.4 million, with the overwhelming majority being of European descent. Most European settlers were of British (English, Scottish, Irish) origin, though smaller numbers of immigrants from other European countries also arrived. Maoris at this time constituted no more than 6% of the population.

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s economy flourished, and the country rapidly became one of the wealthiest in the world.

Sheep farming became the most important industry in the late 19th century. By the 1880s, New Zealand had millions of sheep, and wool exports became the main source of wealth.

The invention of refrigeration in the late 19th century revolutionized New Zealand’s agricultural exports. In 1882, the first shipment of frozen meat left for Britain, marking the beginning of a lucrative export industry. The ability to export frozen lamb, beef, and dairy products allowed New Zealand to supply food to Britain and other parts of the world, creating a booming economy that was largely reliant on agricultural exports.

Between the late XIXth century and the early 1970’s, New Zealand regularly ranked amongst the world’s top 5 wealthiest nations, as measured in per capita income. Wealth was well distributed, with New Zealand developing a robust welfare state, through the early introduction of public healthcare, education, and pensions, all of it supported by the enormous revenue generated from agriculture. During the period 1900 to 1970, New Zealanders boasted one of the highest standards of living in the world.

Then, in 1973, economic disaster hit twice: Britain joined the EU, which meant that New Zealand could no longer export its agricultural products under the same very favourable conditions. In the same year, the global oil crisis meant that the cost of energy skyrocketed for a nation that had to import all its oil.

What is the situation today?

Starting in the 1980’s, the New Zealand government undertook major economic reforms, deregulating the economy, removing tariffs, privatizing state-owned enterprises, and adopting more market-oriented policies. These reforms, though initially painful, modernized the economy and helped it adapt to global market conditions.

New Zealand aggressively began to develop other industries in order to reduce the nation’s dependence on agriculture. Tourism became a major source of revenue, driven by the country’s natural beauty, adventure tourism, and cultural attractions (such as Maori heritage).

The agricultural sector also transformed and modernised, as New Zealand began producing more high-value crops (such as kiwifruit, wine, and specialised dairy products). Heavy investments also occurred in technology and innovation to improve the productivity and sustainability of traditional agriculture. In recent years, the nation has developed a growing high-tech sector, particularly in areas such as agricultural technology, software, and biotechnology. Innovations in these fields allow New Zealand to increase productivity while maintaining its environmental sustainability goals.

Finally, the success of films like “The Lord of the Rings” and “The Hobbit”, filmed in New Zealand, has turned the country into a global film production hub.

Today, New Zealand is no longer in the top 5 wealthiest nations but, at rank 20 to 25, it does better than 85% of the world’s countries. The nation has retained many of the welfare state features it had created during the pre-1973 era, although at a more measured and financially sustainable level.

The success of New Zealand in transforming its economy with common-sense measures and strong government action, should provide a stark lesson to other nations who did not do so when they could have.

As an example, Argentina was one of the world’s wealthiest nations in 1945. Like New Zealand, Argentina had built its wealth starting in the late XIXth century through the export of meat and other agricultural products. While the rest of the world began to re-industrialise after World War II, Argentina instead closed its borders, over time rendering its economy less and less able to compete in international markets. In parallel, one populist government after the other increased welfare payments to a population which, as time went on, became more and more impoverished. Whereas at the end of World War II, Argentina and New Zealand’s per capita income was comparable (among the world’s top 5), today New Zealand ranks in the top 20%, while Argentina is in the bottom 35%. Less than 10% of New Zealanders today live below the poverty line, whereas almost 50% of Argentinians are considered poor.

Culturally, New Zealand today has succeeded in erasing many of the XIXth century animosities between Maoris and Pahekas (Europeans). It’s really interesting, as you visit this nation, to see how much respect the descendants of European whites have for Maori traditions and culture. Most New Zealanders we have met have said to us (whehter they are Paheka or Maori),: “We are now all New Zealanders and we are very proud of our combined past!”.

As you visit the country, you will not only notice that everything is written in two languages, but also that many Maori words have been incorporated into the day-to-day English language you hear (making it sometimes difficult to understand what is being said, if you are not a New Zealander!).

Maoris today represent about 15% of the population, but their cultural presence is everywhere. All you have to do is watch an international rugby match, where each All Blacks game is preceded by a Maori haka warrior dance, ceremoniously performed by a racially mixed team of Europeans and Maoris.

We had the great fortune of spending three weeks visiting wonderful New Zealand, in September/October 2024.

It is impossible to relate here everything we lived through, but we can say for sure that New Zealand is a destination that cannot leave you indifferent. The beauty and variety of the landscapes, coupled with the generosity and kindness of its people, as well as excellent infrastructures (hotels, restaurants, roads, etc.) make it an exceptional destination for anyone interested in nature, discovery and culture. Every road we took was beautiful, every walking path a discovery, every meal a feast of highest quality ingredients (especially if you like meat and dairies).

Here are a few highlights of what we saw and experienced during our (in hindsight, much too short) trip to New Zealand:

Auckland

Auckland is by far the largest city in New Zealand but, at about 1.5 million, it’s small compared to most capital cities around the world (total New Zealand’s population is 5.2 million).

It’s a laid-back city, very spread out, with just a few high-rise buildings (the only ones you will find in New Zealand).

We enjoyed visiting Ponsonby (a charming part of the city, filled with Victorian-age beautifully preserved houses, originally built for the working classes, but today completely gentrified).

We loved strolling on the beaches (there are quite a few) and visiting the majestic Auckland War Memorial Museum, which includes a great description and many objects illustrating New Zealand’s (and especially Maori) history and culture.

Bay of Islands

Bay of Islands is famous for its pristine beaches, crystal-clear waters, and scenic coastline. The bay consists of 144 islands, offering countless coves, inlets, and hidden beaches. These features make it a paradise for boating, kayaking, and other water-based activities.

We stayed at Eagles Nest, near Russell, in a villa in which we would have liked to stay forever! We took long walks, watched Tui birds feast on bright red bushes and watched the sun slowly descend on a totally deserted beach with no sounds other than the numerous Kereru birds singing to each other.

The area of Bay of Islands also has great historic significance because it was in this area that the Treaty of Waitangi, mentioned above, was signed in 1840. We went to the grounds of the signing and spent a memorable afternoon visiting the museum, which offers excellent insights into the early relations between Maori and Paheka (European colonisers).

Lake Rotorua

Lake Rotorua was formed by a massive volcanic eruption around 240,000 years ago. Its volcanic origins contribute to its unique landscape, with volcanic hills and geothermal hot springs surrounding the lake. We loved the peaceful sights of the large lake and spent a very relaxing afternoon at the Waiariki theothermal baths, which included no less than three types of saunas, heated pools with great lakeviews, followed by an intensive mud bath. We left the place floating on a cloud!

New Zealand is a place where almost everything grows, especially large trees. A few minutes from the centre of Rotorua is a large redwood forest, planted about 100 years ago. The trees proved unsuitable for agricultural exploitation, so they just stayed in place and now offer beautiful paths for an afternoon of quiet walks.

A few km south of Rotorua is the Waimangu Volcanic Valley, where we spent an afternoon hiking through spectacular volcanic craters, enormous hot water springs, beautiful geothermal features, rare and unusual plant life, brilliantly coloured microbiology, and a wide array of birds.

It was one of the most scenic and exciting walks we have ever taken, and were sad to leave, so strong was the impression of almost otherworldly colours, scents and scenic views.

Tongariro

The Tongariro Alpine crossing is one of New Zealand’s most mythical treks and we were fortunate to take it on clear (but cold) day. We walked the 20 km (with an elevation difference of 2000m) in 7.5 hours, which is pretty good. Pasta, lamb shoulder and potatoes at the end of our day never tasted as good as on this day.

A rainy day made our walk around Rotopounamu particularly meaningful. This quiet lake, which has great spiritual meaning for Maoris and, accordingly, has never had human constructions or an altered environment, introduced us to the world that Polynesians encountered when they first arrived. We felt reflective and happy, surrounded by the primeval forest, the bird songs and the total absence of humans.

Kaikura

We loved our stay at Hapuku Lodge, the beautiful views from the tree house rooms and the excellent meals served by the cozy fireplace.

While at Hapuku, we discovered on foot and then by air, the stunning Kaikoura Peninsula, mingling with seals and birds at incredibly close distance.

Christchurch

Close to Christchurch we stayed at the amazing Annandale property – only 3 houses on 1’600 hectares of land, surrounded by the ocean…and 5’000 sheep. We stayed at the former sheppard’s cottage. As the evening came, and we sat by the roaring fireplace, we understood why many former generations of shepherds had been so happy here.

The other two properties at Annandale have strikingly modern constructions, but offer the same peace and seclusion as the Sheppard’s Cottage.

When we first arrived in Akaroa, close to Christchurch, we thought: this looks like the lakes in central Switzerland. But in fact, we were looking at the sea! We loved Akaroa’s quiet villages and the long walks by the fjords.

Lake Pukaki

Upon arrival at our lodge at Lake Pukaki, the manager told us excitedly: “You have to come and look at the stars with us tonight, it’s a beautifully clear night!”.

We weren’t very enthusiastic – it was windy and the temperatures looked like they would descend below freezing. We finally went and couldn’t believe what we saw – a magnificent aurora antarctis and incredible views of the Milky Way. We only left after two hours because we were risking hypothermia!

Ahuriri Valley

To awaken at one of the glasshouse rooms on the Lindis property in the Ahuriri Valley is like being transported through time into what the Scottish Highlands must have looked like a few centuries ago. We loved our long walks in this immense property, the amazing food, the very attentive staff and the strikingly contemporary and perfectly executed architecture.

Southern Alps

As we were crossing what New Zealanders call “the Southern Alps”, we initially thought that they looked the same as the European Alps. But then we looked closer and saw that not a single building or road was visible in the many valleys we crossed. And then the magnificent shoreline appeared, the blue immense ocean, and again not a human in sight. This is not the Alps we have always known!

Milford Sound

The Milford Sound is in fact a fjord, one of the many that crowd the southwestern tip of New Zealand. We visited it on a day with bright blue skies and were lucky that it had rained the days before. Apparently it’s only after a rainfall that you see as many waterfalls (we saw hundreds) – without rain there are only two or three (which are still impressive). We were thrilled to see very rare Blue Penguins happily going about their life in the knowledge that they are undisturbed by humans. It was a bit windy and cold but, wow, the spectacular views of such majestic, unperturbed nature made us not even notice it.

Lake Wataka

Lake Wataka, about an hour away from Queenstown, has a hip vibe and looks very much like Bariloche in Argentina. The walkways by the sea have been taken great care of, with many benches and large flat rocks an invitation to picnic. Everyone here eats fish and chips, we wondered why any other food was offered in the many lakeside restaurant.

The food in New Zealand is great because the ingredients are so good (grassfed meat, organic dairy products, organic vegetables), but we wondered whether it could also be imaginative, so we booked at table at famed Amisfield Restaurant close to Queenstown. It took us over 3 hours to go through 13 dishes that as many chefs prepared for us. We were not disappointed – the menu was hugely inventive, leveraging the many local foodstuffs that New Zealand has to offer and wrapped in a presentation that was spectacular. We would gladly return every season, when the menus are adapted to the local climate and Amisfield 13 chefs’ extravagant imagination!

Queenstown

Queenstown is quaint, has a sportive feeling to it, and is surrounded by breathtaking scenery. It’s not a very big town, but it has many good restaurants and a few nice and bustling shops.

As we left New Zealand, we asked ourselves if, given the chance, we would like to return here. Yes, we said enthusiastically. Yes, we would like to again hike above the clouds, marvel at exuberant waterfalls and crystal-clear freshwater springs, take a stroll to a distant solitary lighthouse, watch white fumes raise from a dark blue lake, listen to the sounds of mountain rivers, run after the setting sun on deserted beaches and reflect on what our next life-destination might be, on the shores of one of New Zealand’s many tranquil, hidden lakes.