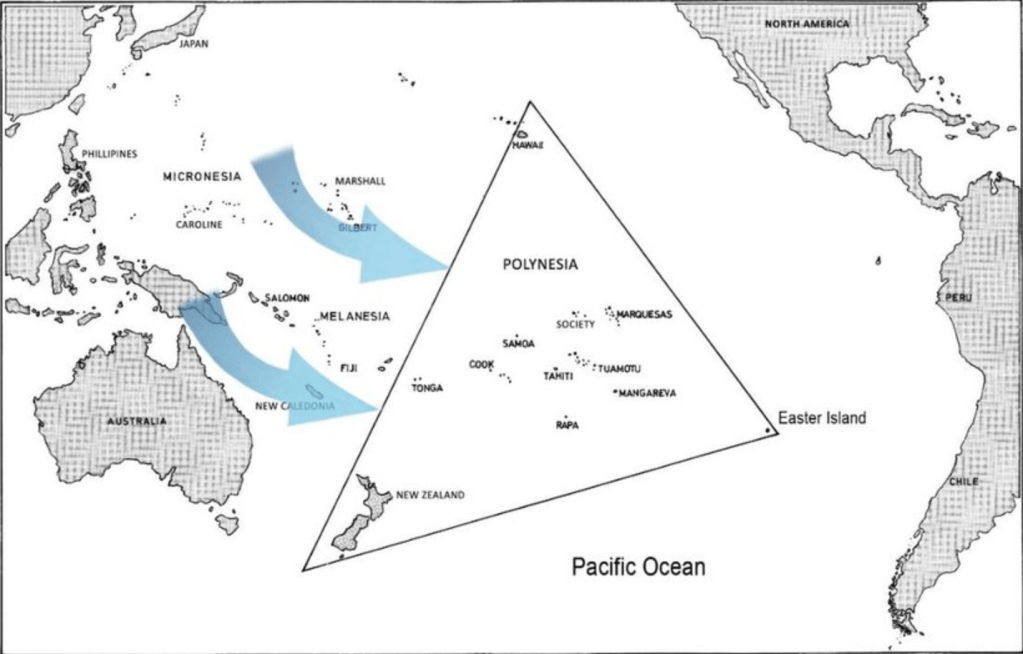

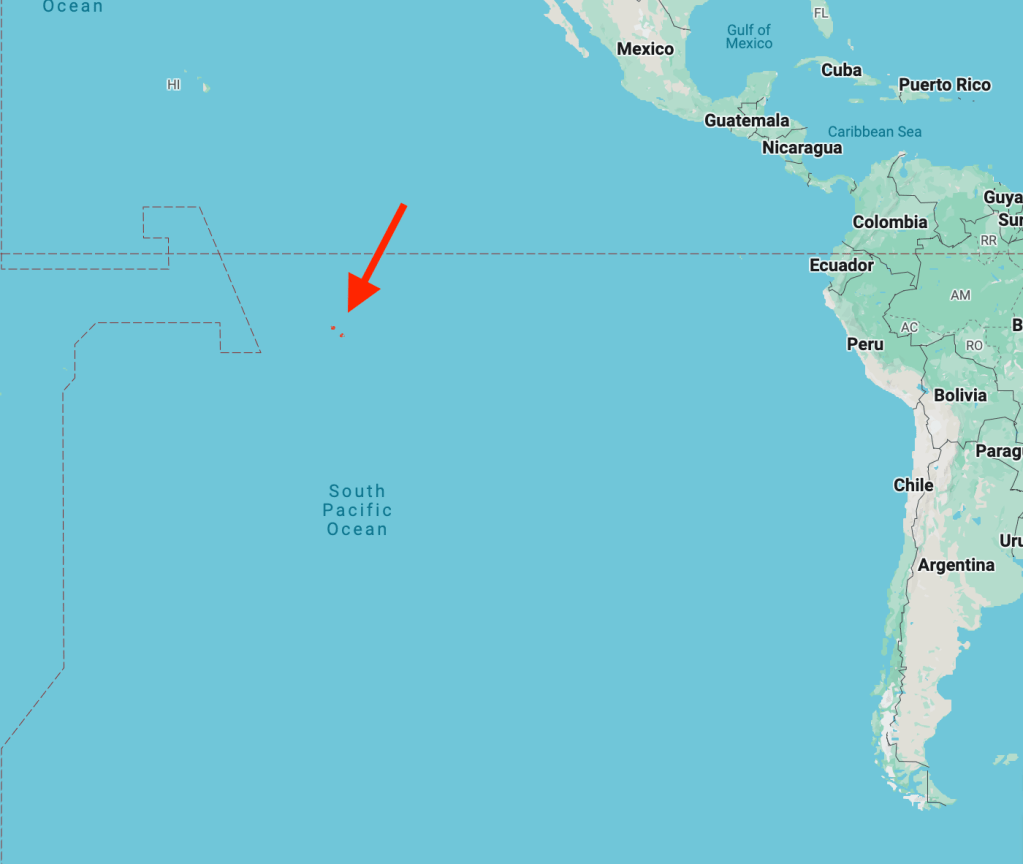

The Polynesian Triangle is defined by three points: New Zealand in the southwest, Hawaii in the north, and Easter Island in the east, encompassing an enormous area. Its history represents one of the most impressive examples of human migration and settlement across the open ocean.

We travelled by boat for 24 days in the Polynesian Triangle, visiting some islands so remote, that their inhabitants only have contact three or four times per year with outsiders.

The Polynesian Triangle is huge, it covers an area of 16 to 18 million square kilometers, which is 3.5 time larger than all of Europe, and twice the size of the US, including Alaska.

More than 98% of the Polynesian Triangle is water. If you exclude New Zealand (which represents 90% of the Polynesian Triangle’s landmass), what is left, put together, is about 30’000 square km, the size of Belgium, but spread over an area that is about 530 times larger.

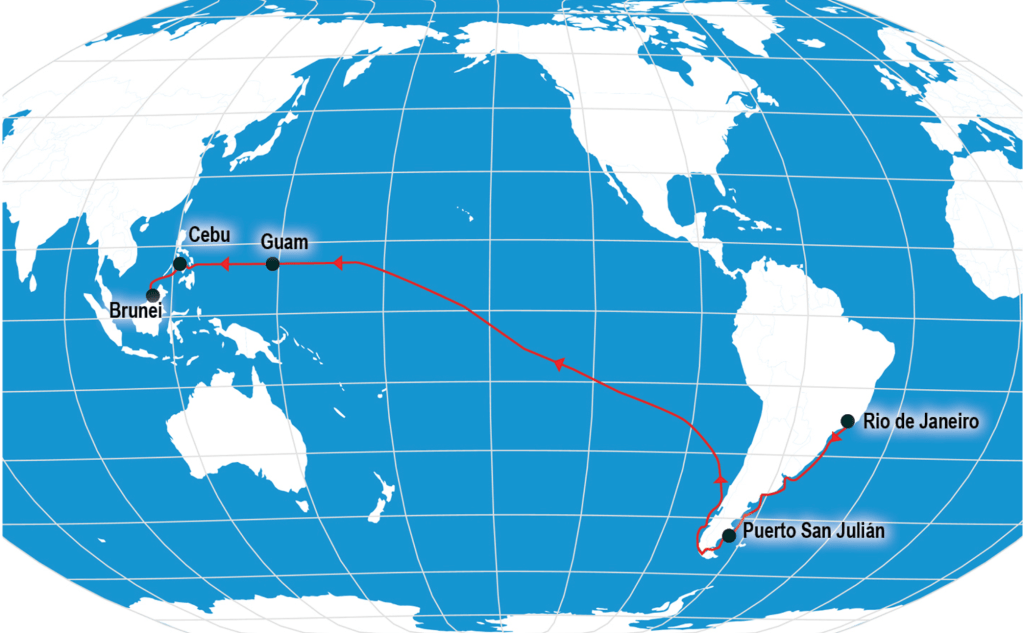

The area is so big and the landmasses so small and so spread out, that Magellan, the first European to visit the area, traversed all of it (plus Micronesia and Melanesia) in 1520/21, without ever sighting land, until he finally he reached Guam, in what is now the Mariana Islands, after travelling continuously for more than three months.

This expansive area is home to culturally connected but geographically isolated communities, who nevertheless share strong linguistic and cultural roots. The sheer size of the triangle underscores the navigational achievements of Polynesian voyagers, who traversed such enormous distances with only stars, ocean currents, and other natural signs to guide them, long before European explorers arrived.

Origins of the Polynesians

The roots of the Polynesians lie in the Lapita Culture, which emerged around 1600 BCE in the Bismarck Archipelago near New Guinea. The Lapita people were part of a broader Austronesian expansion, which began around 3000-2000 BCE from Taiwan and spread through the Philippines, Indonesia, and into the Pacific.

By around 1500 BCE, the Lapita people had settled in Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa, forming the western edge of Polynesia. This region became the cultural heartland of the Polynesians and the base from which later expansions into the eastern Pacific would occur, including a shared language, social structures (such as chiefdoms), and oral traditions that emphasised genealogy and the worship of ancestors.

Around 1000 BCE, Polynesian voyagers began moving eastward into the vast open ocean, embarking on journeys that took them to some of the most remote places on Earth. The impetus was usually given by the younger sons of chieftains who, because they were not the first-born, inherited no land or privileges. By moving onto new territories, this group could become chieftains themselves.

By around 300-800 CE, Polynesian navigators had settled islands in the central Pacific, including Tahiti, the Marquesas Islands, and the Cook Islands. These islands became key centers of Polynesian culture, and the settlers brought with them their language, traditions, and agricultural practices. From there, Polynesians expanded to Hawaii, the Pitcairn Islands and Easter Island. These were extraordinary voyages, covering thousands of miles across open ocean, often requiring the ability to navigate back and forth between islands.

The last major landmass to be settled in the Polynesian Triangle was New Zealand, around 1250-1300 CE (for more details, see our separate report on New Zealand).

European arrivals

Despite sporadic visits to the area (like that of Álvaro de Mendaña at the end of the XVIth century), the European discovery and colonisation of the Polynesian Triangle only really takes place at the end of the XVIIIth century, driven by geopolitical considerations. Both the French and the British wanted to expand their areas of influence starting in the 1760’s and placed settlements in many areas of what is now the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands, Gambier and Pitcairn.

The results were disastrous for the locals. In the Marquesas alone, the population which was estimated at about 100’000 in the 1770’s, shrunk continuously to only about 2’000 people by the 1920’s, the consequence of persecutions, as well as the introduction by Europeans of germs for which the locals had no defences.

Polynesian seafaring

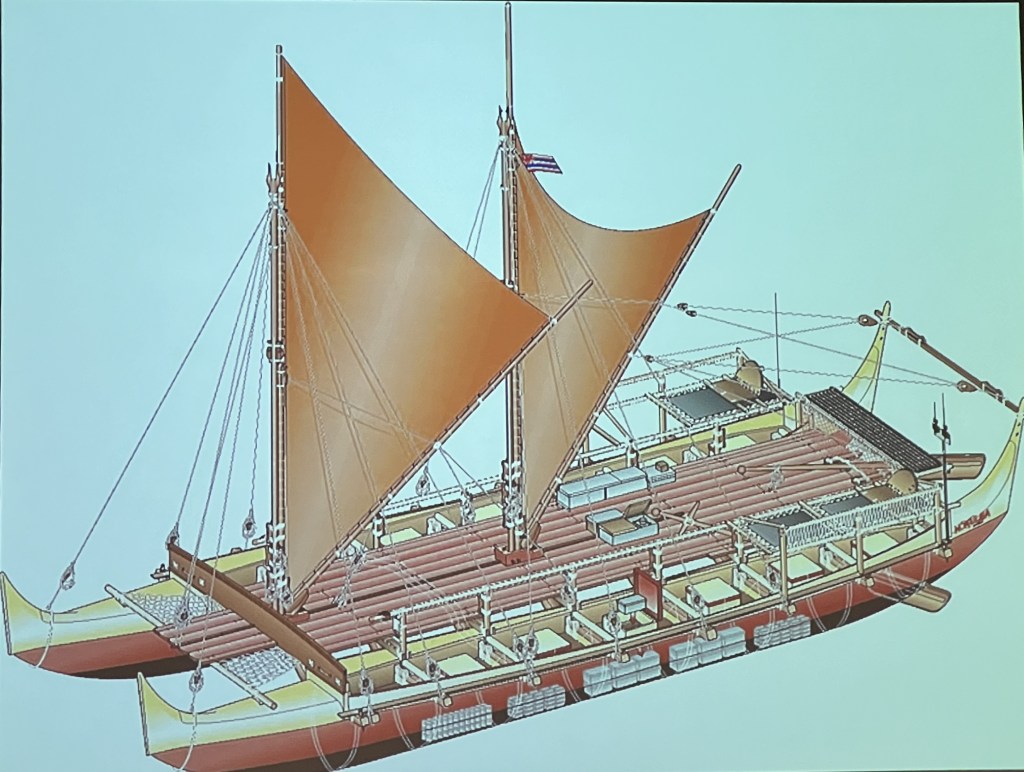

The successful human settlement of the Polynesian Triangle, which started in full at about BC 1000 and was completed by about 1300 AD, was made possible by the extraordinary navigational skills of the Polynesians and their seaworthy canoes. These skills greatly impressed Europeans when they arrived a few centuries later, since they were acquired without any compasses or written records, and were transmitted orally from generation to generation.

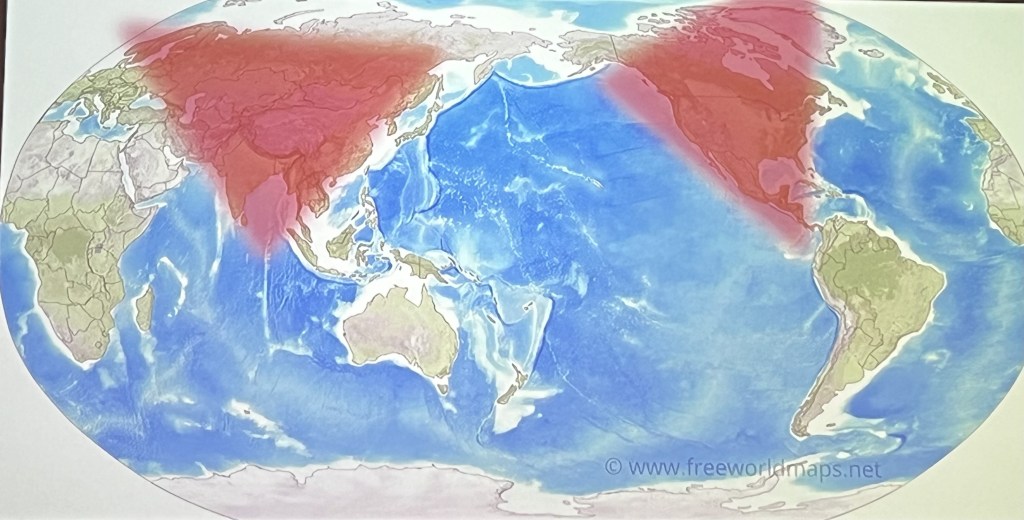

The Polynesian techniques were based on observations of the stars, sun, ocean swells, cloud patterns, and migratory birds, but were incredibly precise, allowing them to travel for upto four weeks on the open sea, without stopping or refuelling on land.

Polynesian canoes were double-hulled and could carry large numbers of people, supplies, and plants needed for colonisation. These vessels were stable and capable of long-distance travel. Each canoe could carry everything needed to establish a new settlement, including taro, coconuts, breadfruit, pigs, and chickens.

Despite the vast distances, to this day the cultures within the Polynesian Triangle share significant similarities.

All Polynesian languages belong to the Austronesian language family and share many resemblances. Oral traditions, including myths, genealogies, and songs, helped preserve knowledge and history.

The marae, a sacred space for religious and social gatherings, is a common cultural element across Polynesian societies, from Tonga to Tahiti to New Zealand.

Tattooing (known as ta moko in New Zealand, tatau in Samoa) was widespread throughout Polynesia, with each culture having its unique styles and meanings. Tattoos were a mark of identity, status, and spiritual significance.

Social Structure

Polynesian societies were generally hierarchical, with status determined by birth, lineage, and demonstrated abilities. The social structure had several key elements:

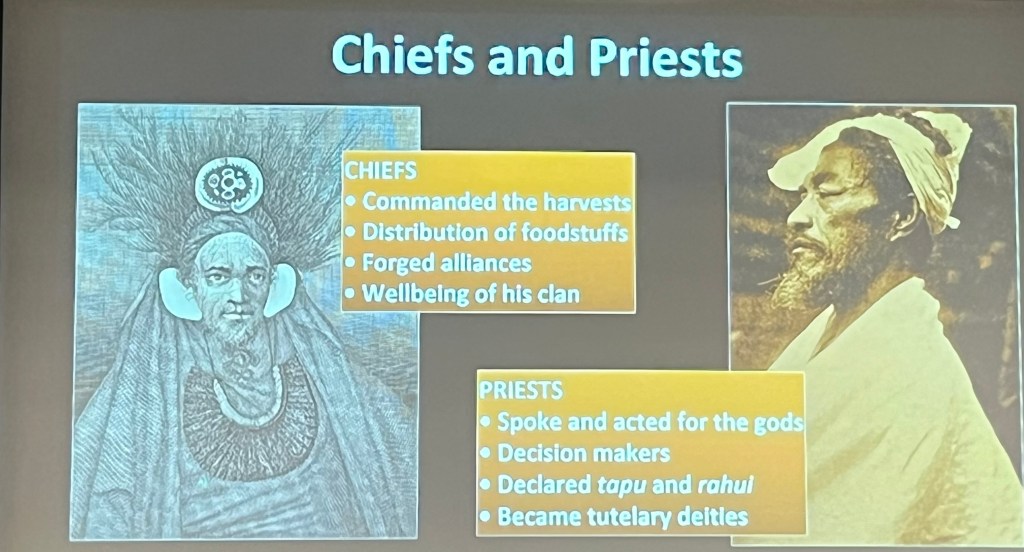

Chiefdoms: most Polynesian societies were organized into chiefdoms, where each community was led by a chief (known as an ariki, ali’i, ariki nui, or matai, depending on the region).

Ariki/Chiefs: the highest-ranking leaders were usually considered descendants of the gods or the first settlers of the islands, giving them both political and spiritual authority. They managed land, organized religious ceremonies, and made decisions regarding war and alliances.

Priests: religious specialists such as tohunga (Maori), kahuna (Hawaii), and others held a significant role, serving as mediators between the spiritual world and the community. They conducted rituals, advised the chiefs, and held knowledge of myths, genealogies, and sacred themes.

Commoners: below the chiefs were the common people, who were typically farmers, fishers, artisans, and warriors. They formed the backbone of the community, working the land and providing for the needs of the society.

Slaves: in some Polynesian societies, such as Tonga and Hawaii, there were also slaves, often captives taken in warfare. These slaves had the lowest status in society.

Tapu and Mana: a central part of Polynesian social structure was the concept of tapu (sacredness or prohibition) and mana (spiritual power or authority).

Mana: it was believed that chiefs and priests had high levels of mana, which made them powerful and gave them the authority to lead. Mana could be increased or lost through actions and behavior. It was closely tied to lineage—those descended from important ancestors were seen as having greater mana.

Tapu: the concept of tapu (known as kapu in Hawaii) governed behavior and social norms. Certain places, people, or objects could be tapu, meaning they were sacred or restricted. Breaking a tapu could have serious consequences, both socially and spiritually, and often required ritual purification.

Religion and Spiritual Beliefs

Polynesian religion was polytheistic, deeply intertwined with the natural world, ancestors, and the sea. Each island group had its unique pantheon of gods, but there were shared deities and spiritual beliefs across the Polynesian Triangle.

Gods and deities: Polynesians believed in numerous gods associated with natural elements, human activities, and the cosmos. Some of the widely revered deities across Polynesia include:

Tangaroa (Tane): God of the sea and marine life. The sea was central to Polynesian life, making Tangaroa one of the most significant deities.

Tumatauenga: God of war and conflict, associated with human struggles and warrior culture.

Rongo (Lono): God of agriculture, fertility, and peace, important for the growth of crops like taro and breadfruit.

Pele (in Hawaii): Goddess of volcanoes and fire, particularly revered in the Hawaiian islands.

Ancestors: Polynesian spirituality emphasized ancestor worship. Ancestors were believed to remain present in the spirit world, influencing the lives of their descendants. They were invoked for protection, guidance, and blessings. Certain ancestral spirits were thought to dwell in specific places, like sacred groves or stones, and rituals were performed to honour them.

Rituals and sacred sites: rituals were central to Polynesian religion, often performed at marae – sacred ceremonial sites that served as centers for worship, community gatherings, and important rites.

Marae were open-air temples, typically raised stone platforms, where offerings were made to the gods, and chiefs conducted ceremonies. These spaces were considered tapu (sacred), and access to them was often restricted to those with high status or during special events.

Oral tradition: oral traditions such as myths, legends, chants, and songs played a vital role in passing down religious knowledge and cosmology. These traditions contained stories of creation, heroic ancestors, gods, and the history of each island group, helping to maintain social cohesion and cultural identity.

Creation of the Earth

While the specific stories of creation vary between different island groups, such as Maori in New Zealand, Hawaiians, Tahitians, Samoans, and Rapa Nui (Easter Island), they share common themes and motifs.

For example, the Maori creation legend speaks about how initially Rangi (the Sky Father), and Papa (the Earth Mother), were locked in a tight embrace. Their union kept everything in darkness, as there was no space between them for light to enter. Rangi and Papa had many children, who were gods, each representing different aspects of the natural world, such as Tane (the god of forests), Tumatauenga (god of war), Tangaroa (god of the sea), and Rongo (god of agriculture).

The children of Rangi and Papa longed for light and space. After many trials, Tane finally succeeded to separate his parents by lying on his back and pushing Rangi upward with his powerful legs, creating a gap between his parents. This act allowed light to enter the world, creating the space needed for life to flourish. Papa, the Earth Mother, remained below, and Rangi, the Sky Father, was lifted above.

Although the separation allowed life to flourish, Rangi and Papa mourned their separation. Rangi’s tears became the rain, while Papa’s sighs became the mist that rises from the earth. Despite their separation, they continued to influence life, and the gods and humans were always aware of their presence.

Family Structure

The family structure in Polynesian society was communal and based on the extended family (or clan).

Polynesian families were typically large, with several generations living together. This extended family unit was fundamental to social organization, with shared responsibilities and collective decision-making.

Members of an extended family shared resources and worked together in activities such as farming, fishing, building canoes, and household chores.

Extended families often lived in village communities, with group housing and communal spaces for activities, reflecting the collective nature of life in Polynesia.

The head of an extended family or clan was usually a senior male or female elder, responsible for managing land, maintaining traditions, and making decisions for the well-being of the group.

Gender roles in Polynesian society were often clearly defined, but both men and women had important responsibilities and spiritual roles. Men typically engaged in fishing, hunting, and building, while women were often involved in planting crops, weaving, and raising children. However, women could hold positions of status and mana (spiritual force), particularly in certain rituals or as priestesses.

Marriage was an important way to form alliances between families or clans, helping to strengthen political ties. Marriages were often arranged by families, especially in the chiefly class, to ensure alliances and social stability. The concept of extended kinship ties meant that family obligations extended far beyond the nuclear family, with strong bonds among cousins, uncles, aunts, and grandparents.

Sexuality

Traditional Polynesian societies had relatively open attitudes toward sexuality, with premarital sexual relationships often accepted and even encouraged as a way for young people to explore their sexuality and to find a suitable partner. These relationships were usually casual, without the strong stigma that European norms later imposed. In some societies, these encounters took place within designated spaces or times where youth could gather without the presence of older family members.

Marriage in Polynesian societies was often based on alliances between families and served as a means to strengthen social ties and political alliances. Marriages were usually arranged, especially among high-ranking families and chiefs, to consolidate status, lineage, and land rights.

Polygyny (one man having multiple wives) was practiced among chiefly families or those with high status, as it allowed chiefs to build alliances with multiple families. This practice was less common among commoners, who generally had monogamous relationships. In some cases, rank and social status influenced who could practice polygyny.

Divorce was generally not stigmatized and could be initiated by either party if the relationship was not working. This allowed a degree of flexibility in relationships, with the focus remaining on family and community harmony.

Polyandry

The existence of polyandry (one woman having several husbands) in Polynesian societies reflects the broader acceptance and adaptability in their approach to relationships. While polygyny, especially in the upper casts, was more common, polyandry served practical and social purposes, prioritising community well-being and social balance when it was practiced.

In areas of the Polynesian Triangle where land and resources were limited, polyandry helped prevent the division of inheritance and property, similar to how it functioned in other parts of the world, like Tibet or parts of India. This practice allowed a family unit to remain stronger and better equipped to manage agricultural land and resources.

For example, the Marquesan society had a flexible approach to marriage and sexual relationships, which included both polygyny and polyandry. Multiple partners were common, and the sharing of spouses between brothers or close male relatives could occur. This helped maintain family cohesion and to ensure shared responsibility for child-rearing and household management.

As in other parts of Polynesia, rank and lineage played a significant role in marital practices. Polyandry in the Marquesas was more likely to be associated with families of higher status, where maintaining control over land and social ties was crucial.

Fluidity of Gender and Sexuality

Polynesian societies recognized a fluidity of gender and sexuality that was often more inclusive than later European concepts. These gender roles extended beyond the binary male and female roles.

Many Polynesian cultures acknowledged the existence of third gender roles or gender-fluid individuals. These individuals played important cultural and spiritual roles in their communities.

In Samoa, for example, fa’afafine are individuals who are biologically male but take on roles and mannerisms traditionally associated with women. They have long been recognized and respected as a distinct gender category, often playing important roles in families and communities.

In Hawai’i, māhū are individuals who embody both masculine and feminine qualities and were traditionally accepted as healers, caretakers, and storytellers. They had significant social roles and were seen as bridging the physical and spiritual worlds.

In some societies like Hawaii, aikane relationships were recognized, referring to same-sex relationships between men. These relationships could be seen as companionships that were respected, particularly among chiefs.

These gender-fluid roles were often considered to have spiritual significance, believed to embody a balance between masculine and feminine forces. This acknowledgment of gender diversity reflects the integrated and holistic view that many Polynesians held toward life, where spirituality and social roles were deeply interconnected.

Leadership Structure in Polynesian societies

Most Polynesian societies were organized into chiefdoms—a type of political structure where a chief held authority over a community or group of extended families.

Paramount chiefs oversaw regional or island-wide territories, with lesser chiefs or sub-chiefs managing smaller districts or villages.

The highest-ranking leaders held authority over larger regions or entire islands, such as in Tahiti, Hawaii, and parts of New Zealand. These chiefs were often considered semi-divine or directly descended from gods, giving them both political and spiritual power.

District chiefs had authority over specific districts, villages, or clans. They managed local affairs and acted as intermediaries between the people and the paramount chiefs.

Village or family chiefs were leaders of smaller clans or extended family groups, overseeing everyday activities and ensuring the well-being of their kin.

Chiefs typically inherited their positions through birthright, with the firstborn or eldest son of a chief often having the strongest claim, but in some cases, firstborn daughters could also play significant leadership roles, especially in spiritual or ceremonial contexts.

The importance of genealogy was central in Polynesian societies. A leader’s right to rule was often justified through whakapapa (genealogical ties), tracing their descent from mythical ancestors or gods, giving them a divine mandate to rule.

The concept of mana (spiritual power or authority) played a crucial role in leadership. Chiefs were believed to possess high levels of mana, which gave them authority and respect among their people. If a chief lost mana through improper behaviour or failure to fulfill his duties, it could undermine his legitimacy as a leader.

Chiefs in Polynesian societies had a wide range of responsibilities, extending beyond mere governance to include spiritual, judicial, and economic roles. They were expected to ensure the prosperity of their people, maintain social order, and uphold rituals and traditions.

Chiefs were often seen as the spiritual leaders of their communities, serving as intermediaries between gods and humans. They led religious ceremonies, made offerings to the gods, and maintained sacred sites such as marae (ceremonial platforms). Their ability to communicate with the spiritual world was believed to be crucial for ensuring abundant harvests, successful fishing, and protection from natural disasters.

Chiefs often served as judges in disputes within their communities. They enforced customary laws and their role in dispute resolution helped maintain peace and social harmony within the community.

Chiefs were also responsible for managing resources, such as agricultural land, fishing grounds, and forests. They organized the allocation of land among families, ensuring that clans had access to the resources needed for their subsistence. They also managed communal activities like building canoes, house construction, and community feasts.

Chiefs played a key role in organising warfare and defense. They were often expected to lead warriors in battle to protect their territories or expand their influence.

While chiefs held significant power in Polynesian societies, there were social norms and customary practices that acted as checks on their authority. In many islands, councils of elders or clan leaders could offer advice to the chief or serve as a balance of power. These councils helped to ensure that a chief’s decisions aligned with the interests of the community. If a chief became tyrannical or misused his mana, the community could withdraw support, effectively reducing the chief’s influence.

A chief’s mana was believed to be affected by his actions. If a chief failed to uphold rituals properly, mistreated the community, or broke tapu (sacred prohibitions), it could result in a loss of mana. This could weaken his spiritual legitimacy as a leader, making it possible for rivals or lesser chiefs to challenge his authority.

In cases where a chief’s rule was considered unjust or if a rival faction emerged, Polynesian communities could experience fission, where a group might break away and form a new settlement or align with a different leader. This was common in Hawaii and Maori societies, where regional alliances and shifting loyalties could change the balance of power.

Did Polynesians reach the Americas before Columbus did?

Evidence supporting pre-European contact between Polynesians and the Americas is found in multiple lines of archaeological, genetic, linguistic, and botanical research. These findings strongly suggest that Polynesian voyagers reached parts of South America and exchanged cultural and biological influences with indigenous populations before the Spanish and Portuguese arrived. Here are some of the most significant pieces of evidence:

- Genetic studies have revealed traces of Polynesian ancestry in Native American populations along the South American coast. These findings suggest that Polynesians and indigenous South Americans interbred, possibly as early as 1200–1300 AD, well before the arrival of Europeans. A 2020 genetic study found Polynesian DNA in samples from indigenous populations on the Chilean coast, providing substantial evidence of pre-Columbian contact.

- The presence of the sweet potato in Polynesia before European arrival is one of the most striking indicators of contact. Sweet potatoes are native to South America, and their introduction to Polynesia points to human-mediated transfer. Linguistic parallels further support this, as “kumara”, the Polynesian word for sweet potato, is identical to its South American Quechua and Aymara counterparts (also “kumara”).

- Chickens are not endemic to the Americas, they could have only been introduced from other areas of the world. Until recently, it was thought that chickens came from Europe, brought by the Spanish and Portuguese in the XVIth century. However, recent chicken remains found in Chile, have been dated between 1304 and 1424, indicating a pre-Columbian introduction of this domesticated animal. These chicken bones have DNA similar to those of chickens from Polynesian islands, which are different to the European breeds. This finding strongly suggests that Polynesians voyaged to the Americas and introduced their animals to indigenous peoples. Indeed, Pizarro upon his arrival in Peru in 1530 was startled to find that the Incas had chickens, which almost certainly arrived from Polynesia via what is now Chile.

- The presence of Polynesian rat DNA in early South American sites also serves as evidence. As we have seen, Polynesians often transported rats on their canoes as they traveled. The identification of this rat species in archaeological sites along the western coast of South America, indicates that these animals most probably arrived with Polynesian voyagers.

- Several of the skulls found in 2011 in Tunquén, Chile, display features atypical of indigenous South American populations, such as elongated skull shapes that bear resemblance to Polynesian cranial features. This unusual morphology makes it likely that these individuals had ancestry linked to Polynesian populations.

- The 1947 Kon-Tiki expedition by Thor Heyerdahl demonstrated that it was possible to navigate from South America to Polynesia (and, of course, vice-versa), using traditional techniques.

Our trip through the Polynesian Triangle

Our 24-day trip exploring the Polynesian Triangle took place in October/November 2024. We travelled from Papeete (Tahiti) to Valparaiso (Chile) on board the Silversea Cloud, an explorer ship.

Below is a short summary of the areas we saw:

Papeete

The usual port of entry into French Polynesia, Papeete is the region’s capital located on the island of Tahiti. It lacks interest and any time here should be minimised. We nevertheless enjoyed a sunet stroll in Papeete’s seafront gardens and a very good meal at L’O à la Bouche.

Fakarava Atoll

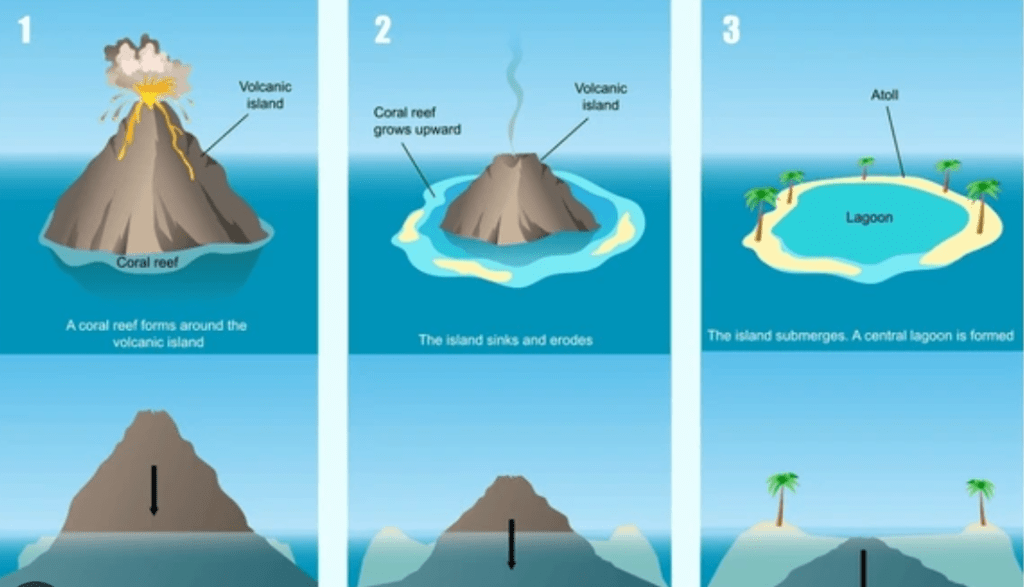

On the way to the Marquesas Islands, we stopped at the large Fakarava atoll in the Tuamotu Islands of French Polynesia, about 400 km northeast of Tahiti. An atoll is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon.

Fakarava is renowned for its exceptional ecological value, earning it UNESCO’s prestigious designation as a biosphere reserve. It is worth a one-day stop, especially if you dive.

Atolls are formed through a combination of volcanic activity, coral growth, and the subsequent sinking of volcanic islands. The process involves the transformation from a volcanic island with a fringing reef, to a barrier reef with a lagoon, and finally to a ring-shaped coral structure surrounding a central lagoon. This entire process can take millions of years, resulting in some of the most beautiful and unique landforms on Earth, characterized by their rich biodiversity and stunning scenery.

Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas are probably the world’s most isolated archipelago. In the middle of the Pacific, they are about 900 km from the Tuamotu Islands, the nearest landmass.

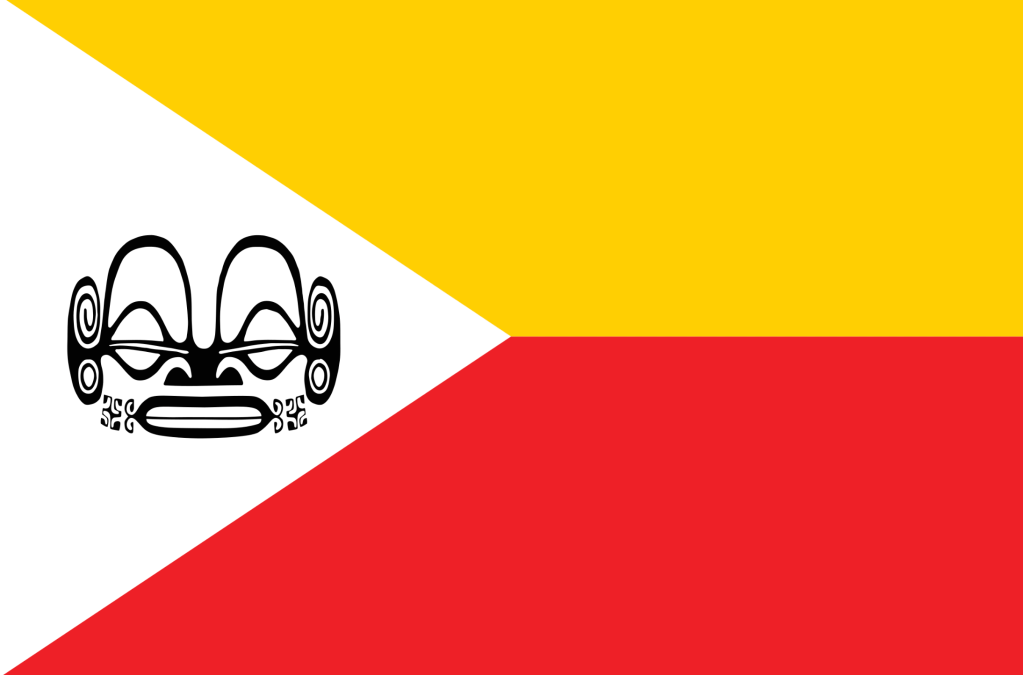

Contrary to the Society or the Cook Islands, the Marquesas have a rugged terrain, with spectacular views and offering great hiking areas. The Marquesas have their own identity and language, and even their own flag, of which the locals are very proud of.

Hiva Oa is one of two biggest islands in the Marquesas and it’s the place where Paul Gaugin, as well as Jacques Brel spent their last years. It has the largest population of the archipelago, which isn’t much (2’200 people). We liked other islands more, although Hiva Oa clearly has its charms too (especially if you are keen on seeing Gaugin and Brel’s tombs!).

Tahuata (meaning “sunrise”) is close to Hiva Oa, is much smaller and more rugged. We took an 8km hike from Hapatoni to Vaitahu, which offered spectacular views.

Nuku Hiva is the largest of the Marquesas Islands. Remote and wonderful, with striking natural features, it has a very sparse population. We took a memorable 13 km hike on Nuku Hiva, in which we encountered only one human being.

Situated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, Fatu Hiva is the most isolated island of the Marquesas, itself the most isolated archipelago on the planet.

Only four boats a year arrive here. We were greeted by songs and dances, and loved meeting the locals (about 600 people live here, spread over two small towns).

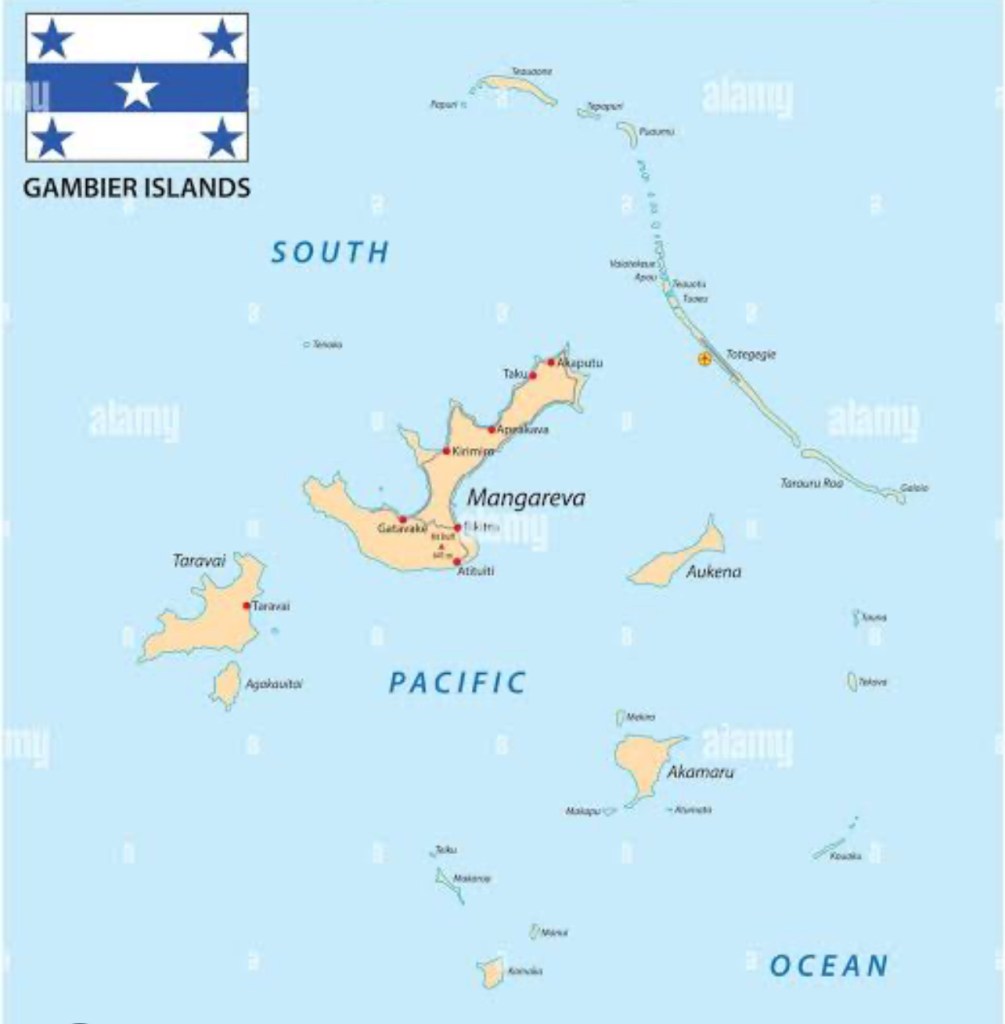

Gambier Islands

Located on the southern tip of French Polynesia, the Gambier Islands are in the centre of a huge atoll, which can only be accessed by small boats.

We visited Mangareva, the largest island and walked up to Mt. Duffy, which offers breathtaking views of Gambier. The return from the top, using ropes, was memorable!

Pitcairn Island

In 1787, the HMS Bounty, a British naval vessel under the command of Lieutenant William Bligh, set sail to Tahiti, with a mission to collect breadfruit plants and transport them to the Caribbean. The British hoped breadfruit could be used as a cheap food source for enslaved laborers in the West Indies.

After a journey of 10 months, the Bounty arrived safely in Tahiti, where the crew stayed for about five months to gather and prepare the breadfruit plants. During this time, many of the crew formed close bonds with the Tahitian people (especially the women) and adapted to the relaxed, warm island lifestyle, which was quite different from their disciplined naval life.

The Bounty set sail from Tahiti on April 4, 1789 with its cargo of breadfruit plants. However, tensions were high. Bligh was known as a strict and often harsh leader, and his disciplinary actions and abrasive manner led to resentment among the crew.

About three weeks after leaving Tahiti, Fletcher Christian, Bligh’s second-in-command, led a mutiny. Christian and a group of 18 other crew members seized control of the ship, while Bligh and 18 loyal crew members were set adrift in a small open boat with limited provisions. Bligh’s remarkable navigation skills allowed him to sail over 3,600 miles to Timor in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and eventually return to England to report the mutiny.

After the mutiny, Christian and the mutineers returned to Tahiti. There, half the men settled, with no wish to leave, whereas the other half collected supplies and, after abducting 18 Polynesians (6 men, 11 women, and 1 child), set sail for a safe place to resettle.

Knowing that the British Navy would pursue them, Christian sought a secluded island where they could avoid detection. After an extended search, the group eventually found Pitcairn Island on January 15, 1790. The island was uninhabited, remote, and incorrectly charted, which they believed would help them avoid being found by the British authorities.

After landing on Pitcairn, the mutineers burned the Bounty to eliminate any evidence of their presence and prevent escape. The remnants of the ship were sunk in Bounty Bay, and some of its timbers were used to build shelters.

Life on Pitcairn rapidly became difficult. The settlers faced limited resources, and tensions between the mutineers and the Tahitian men soon arose, partly due to competition over the Tahitian women, as well as disputes over land allocation, with the Europeans treating the Polynesians with contempt, if not outright racism. The heavy drinking habits of some of the mutineers intensified the already strained relationships with the Tahitian men, who felt mistreated and marginalised by the mutineers.

The community descended into a cycle of revenge killings, with four mutineers initially killed by the Tahitian men, followed by the subsequent revenge killing by the remaining mutineers of all the Polynesian men.

By 1794, only two men were left, John Adams and Ned Young. They realized that if the violence continued, they too would likely perish. This recognition prompted a shift toward establishing peace and stability on the island.

Adams and Young worked to rebuild order among the survivors. They established new rules and worked closely with the Tahitian women, who had also been deeply affected by the violence. The women were essential to survival, as they maintained the island’s agriculture and took on significant responsibilities for the children.

Ned Young, who had some knowledge of the Bible, began teaching Christian values to the community as a way to promote peace and moral order. Adams, initially skeptical, eventually embraced Christianity and began using the Bible to educate the surviving settlers.

In 1799, Ned Young died of asthma, leaving John Adams as the last surviving man, with 11 women and 25 children. Adams assumed a paternal role for the community, taught the children to read and write, and instructed them in Christian teachings and moral values. His leadership and focus on religion and education transformed the settlement from a violent, fractured group into a cohesive, peaceful and stable community.

Pitcairn remained hidden from the outside world for nearly two decades. In 1808, the American whaling ship Topaz stumbled upon the island and was the first to make contact with the descendants of the mutineers. They were surprised to find a small English-speaking community led by John Adams.

When the British discovered the settlement, they chose not to take punitive action, in part due to the isolation of Pitcairn and the established community. Adams was given a pardon for his role in the mutiny, allowing the community to continue.

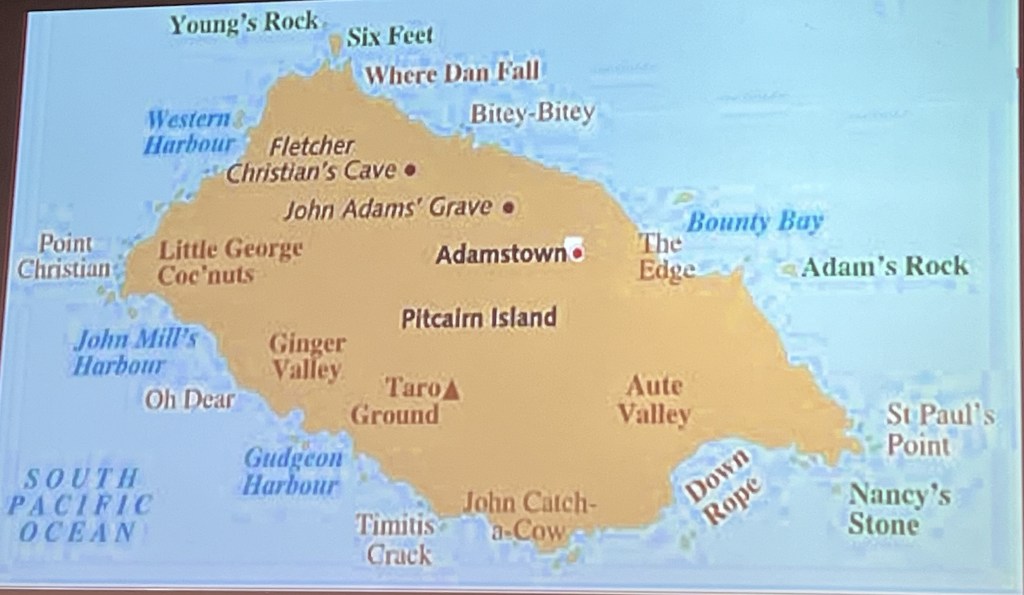

Today, Pitcairn Island remains inhabited by the descendants of the original Bounty mutineers and the Polynesians who accompanied them. The population is small, with currently 42 inhabitants, who are primarily involved in subsistence agriculture, fishing, and tourism. Pitcairners speak a language which is a unique mixture of English and Polynesian. A few examples:

“Where are you going?” -> “About you gwen?“

“How often do ships call here?” -> “Humuch shep corl ya?”

“What food grows on Pitcairn?” -> “Wut weckle groos ana Pitkern?”

“Looks like it’s going to rain” -> “Semme thing given rain”

Pitcairners are an inventive folk, at least when it comes down to naming places on their island. Examples: “John Catch-a-Cow”, “Where Dan Fall” or, more simply, “Oh Dear”.

Pitcairn is not just remote, it is also almost inaccessible.

We were very fortunate to be able to land and spent a truly memorable day on this beautifully green and lush island, where we were warmly received by the Pitcairners, who prepared fish & chips for us and told us many of their life stories.

Easter Island

Easter Island is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world, located approximately 2,000 kilometers from its nearest inhabited neighbor, Pitcairn Island, and over 3,500 kilometers from the coast of South America. It’s believed that voyagers to Easter Island may have launched from Central East Polynesia at about 1200 AD, probably from the Marquesas or the Society Islands, over 3,200 km (2,000 miles) away. This distance meant a journey of about 3 to 4 weeks under favorable conditions, without ever seeing or setting foot on land.

The island’s original Polynesian settlers called it “Te Pito o Te Henua,” which translates as “The Navel of the World” or “The End of Land”. On April 5, 1722, Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen and his crew became the first recorded Europeans to encounter the island. This date happened to be Easter Sunday, leading Roggeveen to name it Easter Island. During the 19th century, Polynesians from other islands began referring to the island as “Rapa Nui,” meaning “Big Rapa,” to distinguish it from Rapa Iti (Little Rapa) in the Austral Islands. This name likely came from voyaging Polynesians or later settlers who recognised a similarity in the landscape or environment between the two islands. Today, Rapa Nui is the name used by the island’s indigenous population and the official name for the island in the Rapa Nui language and in Chilean administrative terms. The islanders prefer this name as it reflects their Polynesian heritage and cultural identity.

The original vegetation of Easter Island consisted of palms and broadleaf forests together with a variety of shrubs, ferns, and grasses, many of which are common to Eastern Polynesia, especially Mangareva and Pitcairn. The island, which is of volcanic origin, is quite big (163 km², slightly bigger than Liechtenstein), has a temperate climate and rich soils, as well as large areas that lend themselves to agriculture. It was, in many ways, a paradise, offering the colonisers large opportunities to multiply and live very well, which they did, at least for a while.

Upon arrival, the Polynesians manipulated the environment and, as they had done in other islands, trying to recreate the cultural and natural settings of their homeland

islands. They actively introduced taro, sweet potato, banana, plantain, yam, kava, squash, turmeric, coconut and breadfruit. In addition, they brought with them medicinal and other useful plants, such as ti (the roots could be fermented and used for alcohol, while the leaves were used for wrapping food), paper mulberry (for making barkcloth used in clothing and bedding) as well as sugarcane (for food and medicinal purposes). They also brought with them chickens and the Polynesian rat, the latter being largely responsible for enormous damage, including the extinction of the endemic Easter Island palm, a huge tree which only existed on this island. There is no archaeological evidence that the first settlers ever introduced pigs or dogs, as was the case on other Polynesian islands.

Despite the incredible distance, the settlement of Easter Island most likely occurred in several voyages and there is evidence that over the following centuries, there was at least sporadic communication with the islands that now comprise French Polynesia. To this day, the descendants of the original settlers are able to speak in Polynesian with people from the Marquesas and Gambier islands.

Soon after their arrival, the Polynesians began create giant statues (called moai, some weighing 20 tons) to honour their ancestors. Archeologist Edmundo Edwards, a specialist on Easter Island notes: “The moai are quite distinct within the context of world statuary, however they share a series of similarities with images that served the same purpose elsewhere in Polynesia. It seems likely that they evolved from similar wooden figures of which there is now no physical evidence.”

Edwards adds: “For Polynesians the head was the part of the body where mana (spiritual force) was stored. Thus it seems reasonable to infer that moai were carved with very large heads to emphasise the supernatural power of the chiefs. The ears of the statues are unusually long despite the elongated shape of the heads because the Polynesians customarily lengthened their earlobes so that these often hung down to the shoulders. The placement of the hands of the moai resting across the abdomen is one of the most common conventions of anthropomorphic figures in Eastern Polynesia and was symbolic of affluence and prosperity. For Polynesians, the abdomen was the seat of emotions and ritual knowledge. In addition, the fingers of the moai are slender with very long nails, alluding to the fact that people of rank did not do manual labour. According to John Macmillan Brown, the extraordinary length of the fingers of the moai may indicate that the islanders elongated their fingers through massage.”

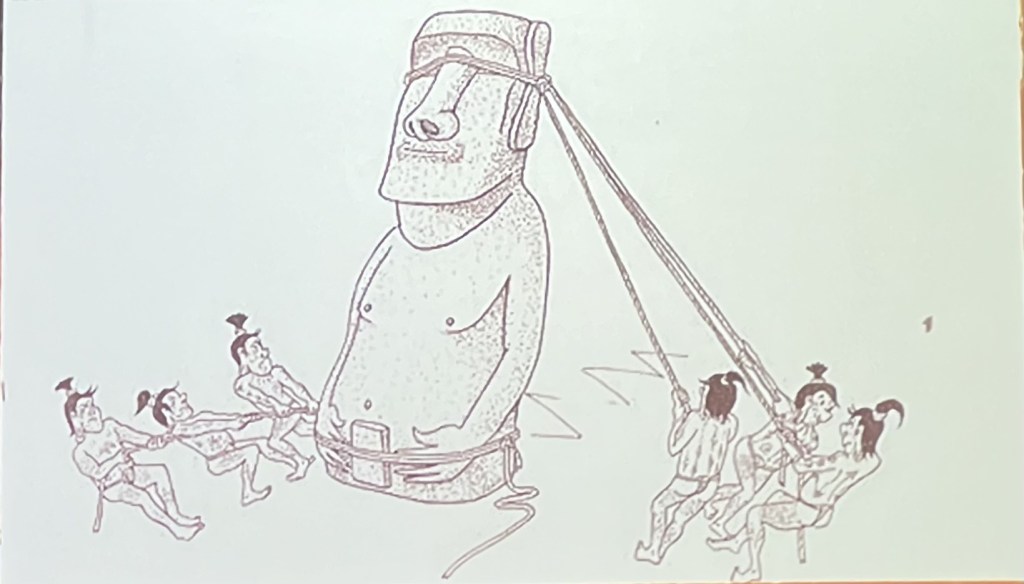

Moais were all manufactured in a quarry located in the center of the island, from where they were subsequently transported to sites facing the villages of the people who ordered them. Some of these villages could be over 10km away from the quarry.

Much has been written about how these giant statues were transported. The current consensus is that there was not one standard way to move them. The transportation methods depended on size (you don’t transport a 2 ton moai the same way as you transport a 20 ton one). Some were transported horizontally, the way you would move a fridge. Others were rolled using large tree trunks. Still others were “walked” to their destination: ropes were tied around the head and base of the moai, and teams of people on each side would pull the statue alternately, causing it to “waddle” forward. No matter how you look at it, the transportation of such huge statues would have taken a lot of time (sometimes years) and involved the work of dozens, if not hundreds of people.

Once erected, the moais were fitted with headdresses and coral eyes. This last event took place on ceremonial platforms called ahu, which served as sacred sites for ancestor worship. Most ahu were built along the coast, with the moai facing inland toward the villages rather than out to sea. This orientation suggests that the moai were meant to watch over and protect the people, connecting the community with their ancestors’ mana (spiritual power).

The eyes were added after the moai were placed on their ahu, and were believed to “activate” the statues, allowing them to channel the spiritual power of the ancestors they represented.

Most moai were also fitted with large cylindrical headdresses called pulao, made from a reddish volcanic stone. The pukao likely represented a topknot hairstyle traditionally worn by high-ranking Rapa Nui men, emphasizing the statues’ connection to the noble lineage and the elite class.

Ahu’s typically had multiple moai’s placed on them, representing the ancestral lineage of a specific clan or community, with each statue honouring a different revered ancestor. As generations passed, successive leaders and ancestors were added to the ahu, creating a visible, lasting representation of the lineage’s continuity and its ancestral power. Each moai would embody the mana of the ancestor it represented, reinforcing the clan’s standing and legitimacy.

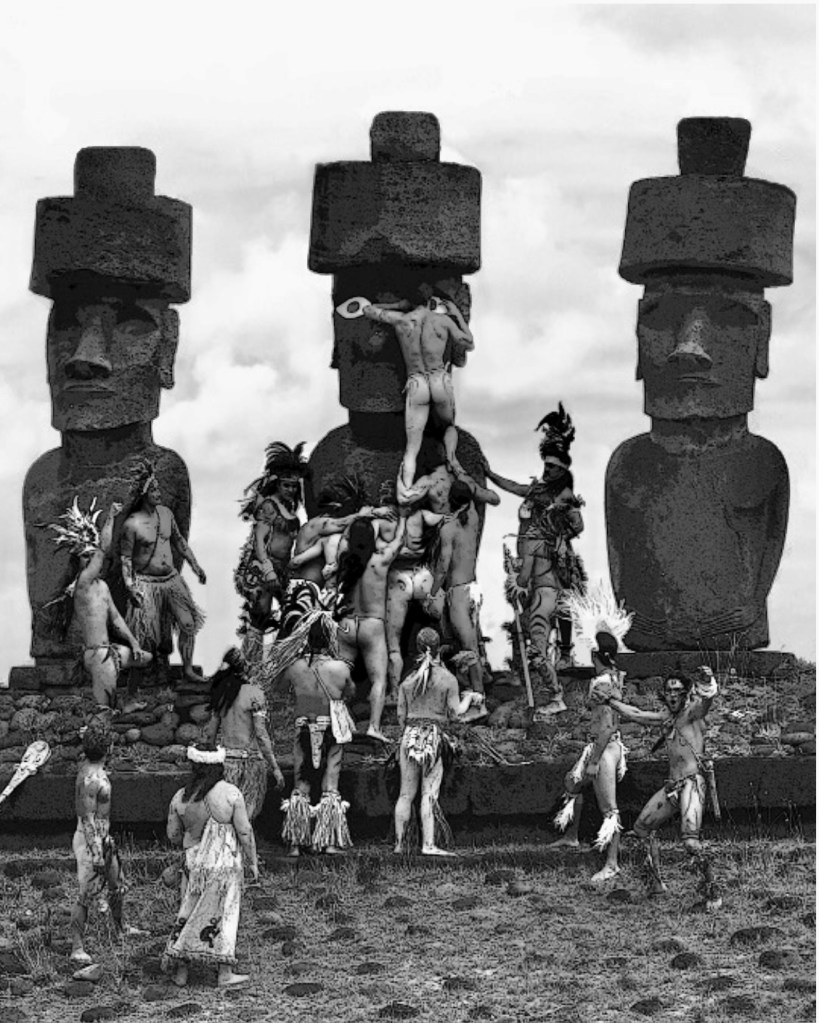

Almost 300 moai were successfully transported and erected on platforms during a period of about 400 years. Then, abruptly, at the end of the XVIIth century, all production of moais stopped, leaving as many as 400 unfinished at the quarry. A further 92 were found along transport routes, suggesting they were abandoned during transportation.

Edwards points out: “After statue-making ceased in the late 1600s and the platforms were gradually destroyed either by natural, but mostly intentional force, petroglyphs of birds (Make Make), and Bird-men were carved over the statues at the quarry and especially on the softer red scoria headdresses that had fallen and rolled to the ground in front of the ceremonial platforms, literally overtaking the Ancestor Cult.”

The abrupt end of moai construction on Easter Island and the subsequent rise of the Tangata Manu, or Birdman Cult, are thought to have been driven by severe ecological, social, and political upheaval on the island. These are the primary factors likely contributing to this shift:

- Deforestation: Rapa Nui was once covered with lush forests, including large palm trees. Over centuries, these forests were heavily exploited for the building of canoes, housing, and especially for transporting the massive moai statues. The resulting deforestation led to a loss of trees, which were critical for both daily life and moai construction.

- Loss of arable land: As trees were cut down, soil erosion became widespread, reducing the island’s agricultural productivity. The depletion of fertile soil impacted the Rapa Nui people’s ability to grow essential crops like sweet potatoes, yams, and taro. The decline in food availability led to famine and malnutrition, putting a strain on the society’s resources.

- Decline in wildlife: The loss of forest cover and depletion of marine resources reduced the availability of food sources such as birds and fish. With fewer resources, social stress and competition for survival intensified.

- Population Growth: Easter Island’s population is estimated to have reached a peak of around 10,000 people by the late 1600s, which would have placed tremendous pressure on the island’s limited resources. As resources dwindled, competition for food, land, and other essentials likely increased, leading to social unrest and internal conflicts.

- Inter-clan rivalries: Archaeological evidence suggests that by the 17th century, rivalries and inter-clan conflicts were escalating. Some scholars believe that the society may have become increasingly stratified, with elites commissioning larger and more impressive moai as symbols of their power. However, as resources ran out, this hierarchical structure began to weaken, and the population may have revolted against the elite class and the old system associated with the moai.

So, in place of the old moai-centered religion, the Birdman Cult emerged, likely as a response to the socio-environmental changes. This cult revolved around an annual competition where representatives of different clans competed to retrieve the first egg of the sooty tern bird from the islet of Motu Nui. The winner was crowned the Tangata Manu (Birdman) and held a position of honor and power for the year.

The Birdman Cult represented a shift in power from hereditary chiefs associated with the moai constructions to a merit-based system, where the winner of the Birdman competition gained prestige. This cult likely offered a more egalitarian system suited to the new social and environmental realities.

We should not, however, think that the shift away from moais was the beginning Easter Island’s descent into chaos, as some writers like Jared Diamond in his bestseller “Collapse” have suggested. In fact, most historians today conclude that the move towards the Birdman Cult was a self-correcting measure taken by the Polynesians to ensure a more sustainable use of resources of an island that has changed considerably since they had first disembarked there a few centuries before.

Indeed, the first Europeans who arrived on Easter Island in the XVIIIth century did not find any famished people there. And there is no evidence, as Jared Diamond pretends, that the island had no more trees, which continued to exist throughout the Polynesian time. Claude Rollin, surgeon major and ethnologist in the 1786 La Pérouse expedition, wrote that “Instead of meeting with men exhausted by famine, […] I found, on the contrary, a considerable population, with more beauty and grace than I afterwards met in any other island; and a soil, which, with very little labour, furnished excellent provisions, and in an abundance more than sufficient for the consumption of the inhabitants.”

The real disaster of Easter Island happened in the XIXth century, with the arrival of Europeans, who through their introduction of diseases and a massive deportation of the natives into slavery in Peru, almost succeeded in killing off the entire population. By 1877, only 111 people survived on Easter Island, an island that had had an estimated 10 to 15’000 inhabitants between 1400 and 1600 AD.

Deep sea marine life

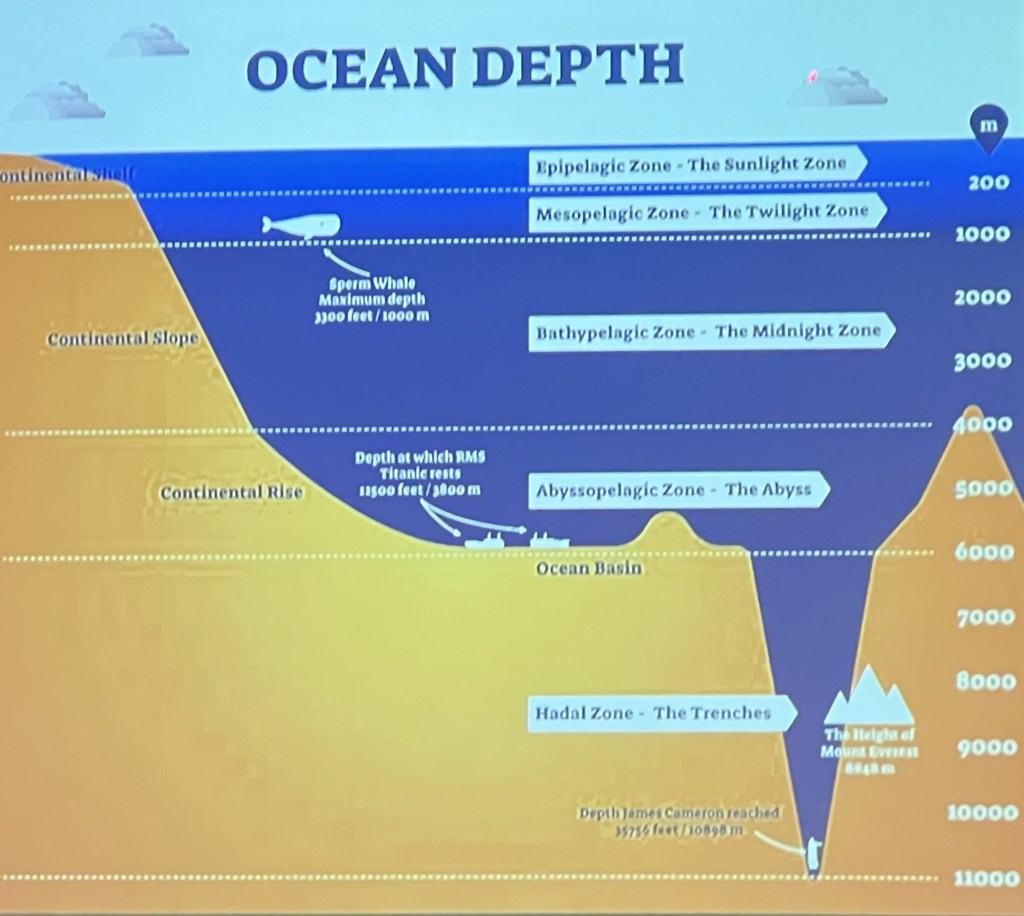

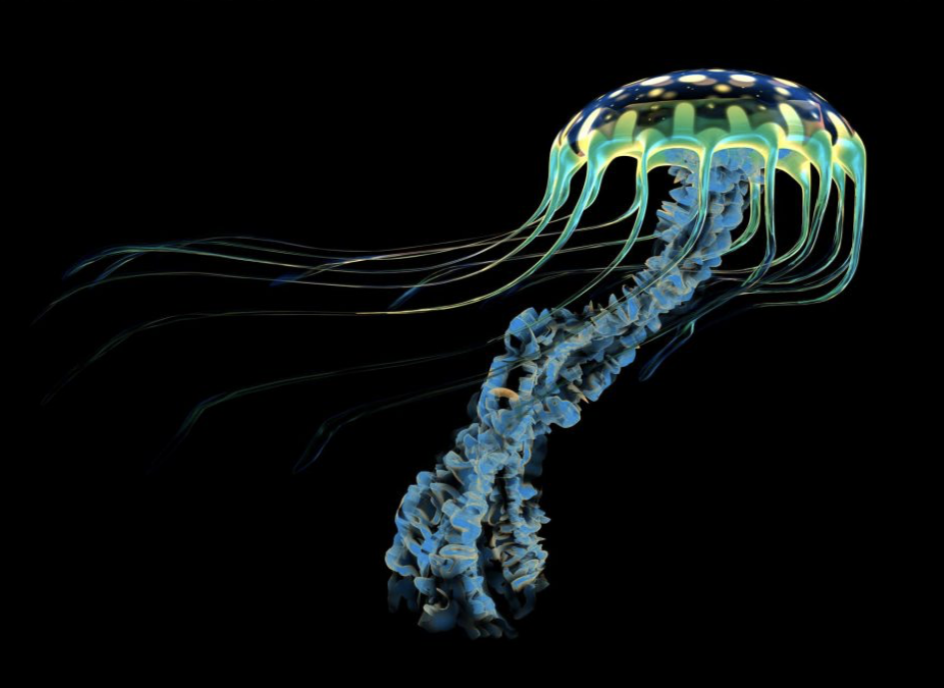

Our discovery of the Polynesian Triangle included 10 days of sea travel (on one occasion, 4 continuous days). As we looked out for hours at the endless sea, we wondered how much marine life there was at the ocean’s depths. As it turns out, a lot!

We are mostly familiar with species that live in areas unto 200m below the sea surface. However, the ocean bed can go down to as low as 11’000m.

Sunlight cannot penetrate beyond about 1,000 meters, making the deep sea pitch black. Many deep-sea species have either evolved ways to produce their own light, or they rely on heightened sensory adaptations.

In addition, temperatures in the deep sea range from just above freezing to about 4°C, requiring marine organisms to have slow metabolisms and specific enzymes that function well in such a cold environment.

Deep-sea ecosystems depend on nutrient “fall” from the surface, called “marine snow,” which includes detritus, fecal matter, and dead organisms. Occasional large food sources, like dead whales (whale falls), can create hotspots of life for decades.

In addition, hydrothermal vents act as oases of life. The energy from chemical reactions, rather than sunlight, supports these communities through a process called chemosynthesis, fuelling dense populations of bacteria and their consumers.

Life at these depths is abundant in certain pockets and sparse elsewhere. Vast regions of the deep sea appear empty, but closer inspection often reveals that even the seemingly barren seafloor has a community of specialized creatures adapted to survive on minimal resources, whether through scavenging, detritus consumption, or unique survival strategies like chemosynthesis.

Some extraordinary creatures live in the deep sea. Below are a few examples:

Seabirds

During the long days when we were travelling through open water, with the coastline thousands of km away, we often wondered about seabirds which, curious about us, frequently flew by our ship, observing us from a distance.

Some of these seabirds we saw spend most of their lives in the air, often flying for days, weeks, or even months without stopping. These birds have remarkable adaptations that allow them to remain airborne for such extended periods of time.

Wandering albatrosses are huge birds that can spend years at sea without returning to land, only coming ashore to breed. They use a technique called dynamic soaring, which involves riding wind gradients above the ocean’s surface, allowing them to travel thousands of km with minimal energy.

Frigatebirds are another exceptional example of seabirds that can stay in flight for weeks or even months flying over the open ocean. They have a lightweight frame and long, narrow wings that allow them to ride thermal air currents. These birds also have the unique ability to sleep in brief bursts while in flight, resting one hemisphere of their brain at a time.

How do such birds drink water, when all they have is seawater?

When seabirds drink seawater, the salt is absorbed into their bloodstream. The salt glands then pull the salt from the blood and excrete it as a concentrated saline solution, which typically drips out through the bird’s nostrils or runs down grooves in their beak. This allows them to drink seawater without suffering from dehydration, a process essential for their survival, especially when they spend long periods far from freshwater sources.

Birds like albatrosses and frigatebirds don’t need to drink very frequently because they can also get some hydration from the food they consume. When they do need to drink, they can skim water off the ocean’s surface without stopping or landing, allowing them to stay in continuous flight.

Silver Cloud

Our 24-day travels throughout the Polynesian Triangle was on the Silver Cloud. We really liked the experience.

With a maximum capacity of 220 passengers, the boat is neither too big nor too small. It includes 4 restaurants, offering sufficient variety for this relatively lengthy trip.

Land excursions were frequent and well organised on Zodiacs. Most important for us: the staff included 13 scientists and researchers, offering dozens of lectures on subjects ranging from history to ornithology, anthropology, climate change and conservation. Lunches and dinners offered additional time with these incredibly knowledgeable and passionate people, something we really enjoyed.

This is a small video summarising our travel through the Polynesian Triangle, prepared by Silver Cloud’s team.