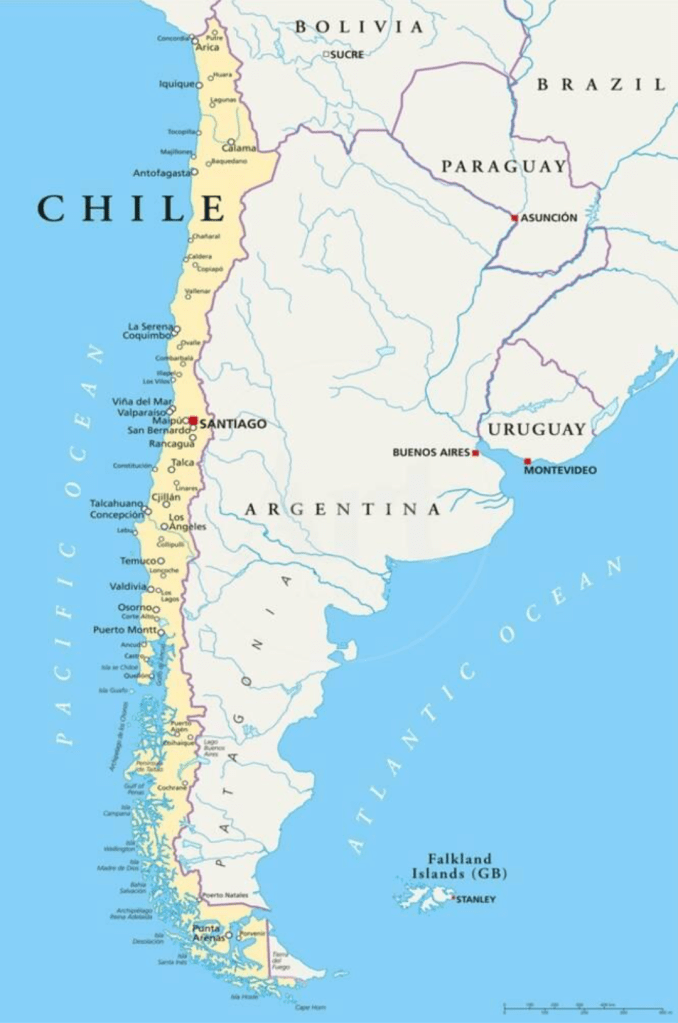

Stretching along the western edge of South America for over 4’300 km, Chile is the longest country in the world. This extreme length gives Chile a remarkable diversity of climates and landscapes, from the Atacama Desert in the north to the icy fjords and glaciers of Patagonia in the south.

Distance and climates also implies varieties of culture, so the fascination of Chile is also the diversity of its population and of its heritage, from the Polynesians on Easter Island (see our separate report on the Polynesian Triangle) to the Aonikenk tribe in the south of the country.

Whereas neighbouring Argentina is mostly culturally homogeneous (especially the area around Buenos Aires, where most of the population lives), Chile is culturally very diverse because of its extremely diverse geography and its distance to European centres. Today’s Chile is more conservative as neighbouring Argentina, and while everyone speaks Spanish, the presence of indigenous populations is felt much stronger than in Argentina, where the indigenous population is smaller and located mostly only in the northwest of the country (see our Argentina report, which includes a section on the Diaguita Indians).

Overall, today’s Chileans struck us as rather introverted (certainly when compared to the typically boisterous and extroverted Argentinians), kind, but not always very ambitious. In the words of the great Chilean writer Isabel Allende: “Chileans throughout their history learned not to speak out, not to hear, and not to see.”

We visited four areas in Chile: the Atacama desert in the north, Easter Island (see our separate report on the Polynesian Triangle), the Juan Fernández Islands and Santiago, the capital.

The first settlers

The first people to settle in what is now Chile were groups who migrated to the region tens of thousands of years ago, most likely from Asia via the Bering land bridge during the last glaciation and later through other routes into South America. These early settlers found extraordinary ways to adapt to Chile’s diverse environments, from the arid Atacama Desert in the north to the icy landscapes of Patagonia in the south.

In fact, the earliest known archeological site in the Americas is not found, as you might expect, in North America, but in Monte Verde, in the south of Chile, dating back to 18’500 BC, long before anyone had until recently thought that humans at reached the American continent.

As time went by, many different cultures emerged in what is now Chile. We will focus on three: people who lived in the desert, those who lived in the extremely cold and damp south, areas which we visited in November 2024. We are also commenting on the brave Mapuche, who resisted both Spanish and Inca invasions, and were quite independent until the end of the XIXth century, and constitute to this day an important element of Chile’s identity. We will also speak about the Juan Fernández Islands, uninhabited at the time of the Spanish conquest. They provide an example of what happens when homo sapiens arrives in virgin lands.

Living in the Atacama desert

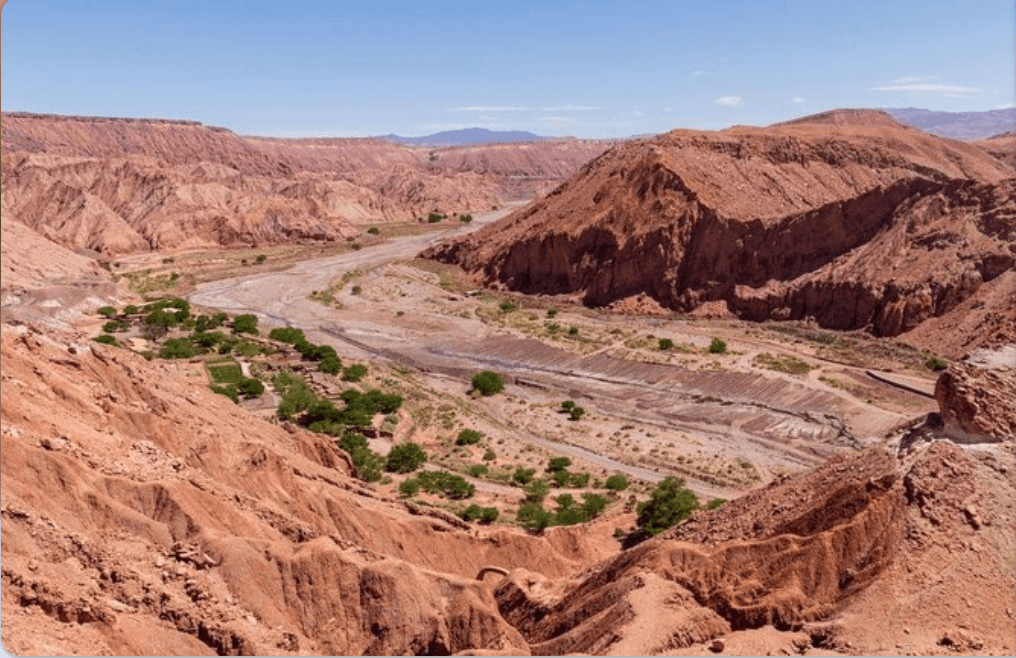

The Atacama Desert is one of the driest places on Earth. The core of the desert receives less than 1 millimeter of rainfall per year. Parts of the desert, such as Arica and in the central Atacama, have recorded no rainfall for hundreds of years. This is because the Atacama area lies in the rain shadow of the Andes mountains. Moist air from the east loses its moisture as it rises and cools over the Andes, leaving the Atacama arid. Moreover, Atacama sits under a persistent high-pressure system over the Atlantic, which inhibits cloud formation and precipitation.

And yet humans have not just lived, but prospered and created a remarkable culture in this area for many thousands of years, providing a testament to human ingenuity and resilience. The most notable group associated with this region are the Lickan Antay, who developed innovative ways to secure food, water, and shelter, leaving behind a rich cultural and archaeological legacy.

Seen from a distance, it looks like the Atacama desert is completely inhospitable. However, here and there, water sources (mostly underground) are available. One of them is located in what is today San Pedro de Atacama, where the Lickan Antay found an underground spring.

Starting in about 2’500 BC, the Lickan Antay started to plant drought-resistant crops in the area, such as quinoa, maize and potatoes, using terraced fields to conserve soil and water. These terraces exist to this day. They also domesticated llamas and alpacas for meat, wool, and transportation.

Over time, the Lickan Antay started to produce high-quality woven textiles made from llama and alpaca wool, which they decorated with beautiful, intricate patterns.

Next, these innovative people, established long-distance trade networks stretching for thousands of kilometres with neighbouring tribes. In exchange for salt, copper, turquoise and other precious stones, which are plentiful in Atacama, plus their exquisite textiles, the Lickan Antay received fish, shellfish, dried seaweed, and other marine products from coastal inhabitants, mostly from the Chinchorro and other fishing communities.

From Andean Highland peoples, the Lickan Antay received preserved meat, gold and silver, high-quality ceramics and coca leaves, which they used for rituals, medicinal purposes, and as a stimulant to combat fatigue and altitude sickness.

By the time the Incas from what is now Peru arrived in the area, in the XVth century, the Lickan Antay were a rich people who had developed a sophisticated and thriving culture.

The Lickan Antay organised themselves into small, tightly-knit communities, often led by elders or spiritual leaders. Villages worked together to manage water resources and agriculture, reflecting a highly cooperative social structure. Because trade played such a significant role for them, the Lickan Antay, like the Polynesians, became open to outside influences, but retained a social and spiritual setup that reflected the environment they lived in. Accordingly, leadership focused on cooperation rather than dominance, as managing resources like water and food required communal effort.

Tasks were distributed based on skills, age, and gender: men typically handled agriculture, herding, and construction, women were involved in weaving, pottery, and household tasks, while elders served as advisors and mediators.

The Lickan Antay were not bellicose. They did build impressive fortified settlements (such as the Pukará de Quitor), but this was to defend themselves against external threats, not to fight each other. While they resisted external domination, including the expansion of the Inca Empire, they also engaged in negotiations and exchanges to maintain autonomy.

Their incorporation into the Inca Empire in the XVth century was generally peaceful and the Incas were wise enough to leave the locals plenty of autonomy. Open for new ideas, the crafty Lickan Antay were quick to learn from the Incas.

The introduction of advanced techniques for constructing terraces on hillsides allowed for more efficient farming in the arid and mountainous terrains surrounding their oases. The Incas also introduced qanats (underground canals) and aqueducts to bring water to hitherto drier areas, and brought with them organic fertilisers such as guano (bird droppings) to enrich the soil, increasing crop yields.

New types of storage facilities for surplus crops were also introduced, ensuring food security during droughts or famines. New varieties of potatoes, as well as llucuma and cherimoya (native fruits to the higher Andean regions), were brought with the Incas, which greatly improved the locals’ nutrition. With the Incas also came new preservation methods, such as ch’arki (freeze-dried potatoes). Finally, the Incas did a lot to improve the road system, which helped the locals to improve their trade with neighbouring peoples. So, overall, the arrival of the Incas was not a bad thing for the Lickan Antay.

The Lickan Antay spirituality

The Lickan Antay believed that all natural elements, such as mountains, rivers, and stars, were alive and imbued with spiritual energy. Mountains were considered powerful spiritual beings that influenced weather, water, and fertility. Volcanoes held special significance as sacred entities and were central to their cosmology. Celestial bodies such as the sun, moon, and stars were revered as deities. Water, a scarce and life-giving resource in the Atacama Desert, was central to their spirituality. Rituals often sought to ensure rain or preserve water sources.

Rituals involved offerings of food, textiles, and pottery, often buried in sacred sites or placed on altars to honour deities. The dead were buried with goods such as tools, food, and ceremonial objects, reflecting a belief in the afterlife.

As for many other animistic peoples around the world, the shaman was the primary religious leader in Lickan Antay society, serving as a mediator between the physical and spiritual worlds. Shamans conducted healing rituals using medicinal plants and spiritual invocations, interpreted celestial signs and omens to guide agricultural and communal activities, and led ceremonies to honour nature spirits, ensure water availability, and bring prosperity.

When the Incas arrived, the Lickan Antay blended their beliefs with Inca religion, creating a syncretic spiritual system. The Incas did not have a fundamentally different religion, so some of the Inca gods (like Inti, the Sun God and Pachamama, the Earth Mother) were just added to the Lickan Antay pantheon. As had happened in Roman times, expansion of the empire just meant that the family of gods got a bit bigger.

All of this would change with the arrival of the Spanish in the 1540s. As in the rest of the American continent, the Spanish’s brutal conquest included the imposition of the encomienda system, under which Indigenous people were forced to work for Spanish settlers in exchange for supposed “protection” and conversion to Christianity. The Spanish also brought with them diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, from which the Lickan Antay had no immunity. These diseases, combined with violence and forced labor, caused a 50% to 90% population decline in the following 100 years.

Nevertheless, some of the Lickan Antay traditions have survived to this day (although not Kunza, their language). For example, celebrations of Pachamama and reverence for nature have continued under the guise of Catholic saints’ festivals. The tradition of creating woven textiles from llama and alpaca wool continues, featuring geometric patterns that often carry symbolic meanings, are still very much alive. And the Lickan Antay’s distinctive ceramics with geometric designs inspired by the Atacama desert remain a hallmark of their culture to this day.

Surviving in the extreme cold of Patagonia

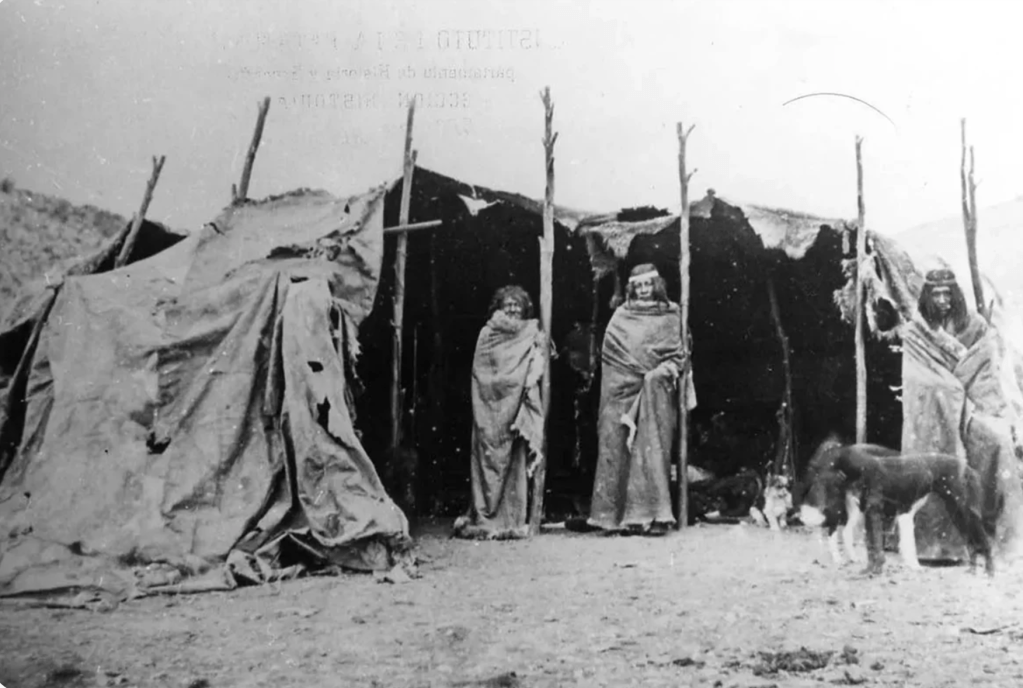

The Aonikenk, also known as Tehuelche, were indigenous peoples who lived in the Patagonian steppes, including the area around the majestic Torres del Paine. It’s a part of the world where even in summer the temperatures rarely rise above 5° C. Almost every day it rains and the winds are so strong that it’s difficult to walk without being blown off your feet.

Notwithstanding the extreme weather, the Aonikenk inhabited and prospered in the vast open steppes and valleys of southern Patagonia, from the Río Negro in present-day Argentina to the Strait of Magellan in Chile, including the area around Torres del Paine. Their way of life, spiritual beliefs, and social structures were deeply connected to the challenging environment of southern Patagonia, which they navigated with remarkable skill and adaptability.

Contrary to the Lickan Antay, they were hunter-gatherers, relying heavily on the guanaco, which provided them with food, clothing, and materials for tools and shelter. They hunted guanacos using bolas (a throwing weapon made of stones tied together with leather cords) and bows and arrows. Other prey included rheas (ostrich-like birds) and smaller animals. During the summer months, they gathered berries, roots, and wild fruits, including calafate berries, which were an important seasonal food source.

For shelter, the Aonikenk built toldos, portable tents made of guanaco hides stretched over wooden frames. These shelters were lightweight and could be easily transported during their frequent migrations.

For clothes, they wore cloaks made from guanaco hides, carefully sewn together with sinew, to protect against the cold and wind.

Men and women also adorned themselves with body paint and ornaments made from bones, feathers, and stones, often for ceremonial purposes.

The Aonikenk were highly mobile, moving across their territory in small groups to follow seasonal resources. They traveled on foot, sometimes covering vast distances.

They lived in small, family-based groups, with each group responsible for a specific territory that provided hunting and gathering grounds.

Groups collaborated for large-scale hunts or during ceremonies but were otherwise largely autonomous.

Leadership was informal and based on experience, wisdom, or hunting skill rather than hereditary authority. As in most other indigenous American groups, elders played a key role in decision-making and maintaining oral traditions.

The Aonikenk spirituality

The Aonikenk had a rich and complex spiritual worldview deeply tied to their natural environment and way of life.

Their spirituality revolved around animism, the belief that all natural elements—animals, plants, rocks, and landscapes—are imbued with spirits. The guanaco was particularly sacred, as it was central to their survival. Special rituals were conducted before and after hunts to honor the animal’s spirit.

As in the case of the Lickan Antay, the Aonikenk spiritual leaders were shamans who mediated between the physical and spiritual worlds. They conducted healing rituals, guided ceremonies, and interpreted omens or dreams. As elsewhere, shamans used plants, chants, and dances in their practices, invoking spirits for guidance, protection, or healing. Body painting and songs were important elements of their ceremonies, with specific patterns and melodies reflecting spiritual meanings.

The Aonikenk had an intimate knowledge of their environment, understanding the behaviour of animals, seasonal changes, and the availability of resources. As with most other hunter-gatherer societies around the world, their practices were sustainable, ensuring the regeneration of the ecosystems they depended on.

The Aonikenk were not inherently bellicose but were capable of defending themselves and their territories when necessary. They were primarily a peaceful and self-sufficient people who valued their autonomy and worked to maintain harmonious relationships with their environment and neighboring groups. The Yamana and Kawesqar, maritime hunter-gatherers living in the coastal and island regions of Patagonia, had occasional interactions with the Aonikenk. The Yamana and Kawesqar occupied different ecological niches, relying on marine resources, while the Aonikenk were terrestrial hunters. The ecological complementarity of these groups minimised direct competition, fostering trade or neutral relations rather than conflict.

The real conflict came when the Europeans arrived, as settlers began encroaching on the Aonikenk lands and disrupting their way of life. With the arrival of Europeans in larger numbers and the wide-ranging introduction of sheep and cattle farming in the 1850’s and 1860’s, relations turned hostile, leading to violent confrontations. Sheep grazing, in particular, disrupted the guanaco population and degraded the land, depriving the Aonikenk of their primary food source and hunting grounds.

As elsewhere in the Americas, the combined effects of displacement, disease, and violence caused a catastrophic decline in the Aonikenk population. Before European arrival, there were an estimated 3,000 and 5,000 individuals, spread across southern Patagonia from the Río Negro to the Strait of Magellan. Sadly, by the mid-20th century, only a few individuals remained, and much of their language and traditional knowledge had been lost. Most descendants today are of mixed heritage, reflecting centuries of intermarriage with other indigenous groups and settlers. Their language has been lost, and what is left of their culture is mostly found in museums. However, efforts by the Chilean government to preserve the Aonikenk heritage have recently been made, as their legacy remains a vital part of the history and identity of southern Patagonia.

The Mapuche’s brave fight

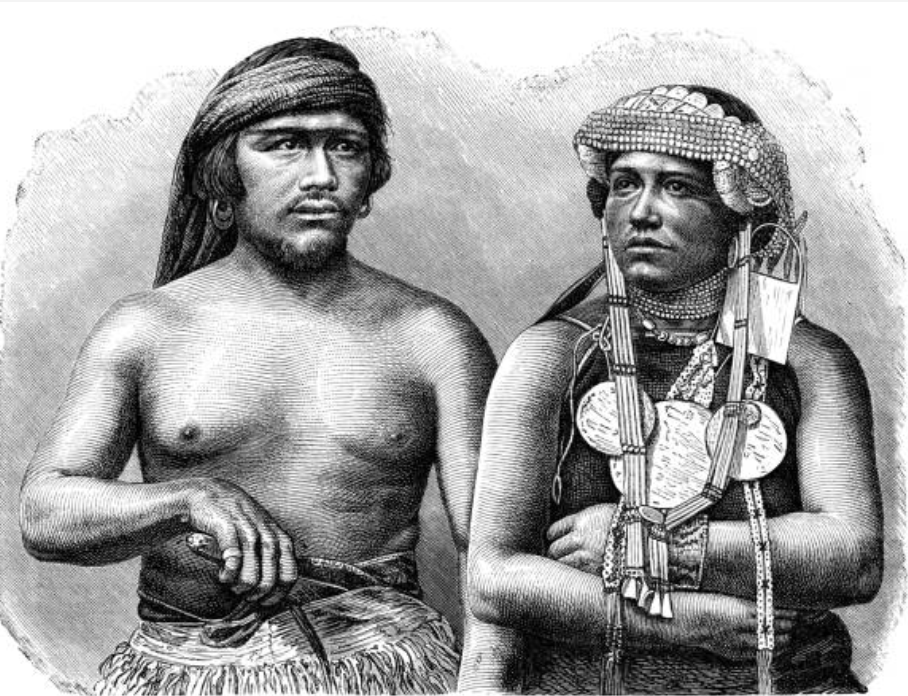

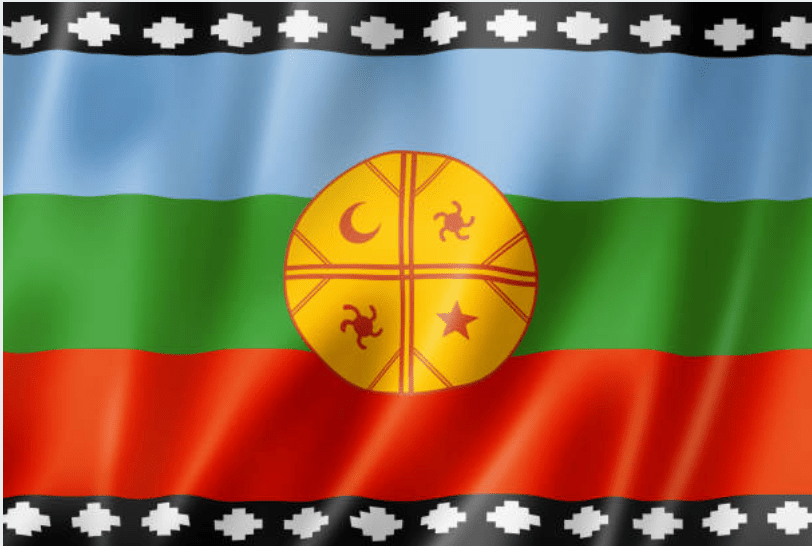

The Mapuche, an indigenous group living in what is now central Chile, successfully resisted domination by both the Inca Empire and European colonizers, maintaining their autonomy for centuries. Today, they remain the largest indigenous group in Chile and one of the most significant in Argentina, continuing their fight for cultural preservation and territorial rights.

The Mapuche speak Mapudungun, meaning “language of the land.”

Traditionally, they were semi-nomadic agriculturalists and hunter-gatherers, cultivating maize, potatoes, and quinoa, raising llamas, while hunting in the forests and grasslands of central Chile and Argentina. They lived in rukas, large thatched houses built from wood and straw, designed to shelter extended families.

The Mapuche were organized into lof or kinship-based communities, each governed by a lonko (chief). During times of conflict, multiple lof would unite under a toqui, a war leader chosen for his strategic and leadership abilities.

As with most other indigenous peoples of the Americas, the Mapuche spirituality is animistic, emphasizing harmony with nature and reverence for the land. Central to their beliefs is the ngen, spirits or owners of natural elements like rivers, forests, and mountains. Machis, spiritual leaders or shamans, play a vital role as healers, mediators with spirits, and leaders of ceremonies. The Nguillatun is one of their most important ceremonies, involving prayers, offerings, and dances to ensure harmony and abundance.

The Mapuche are skilled in weaving, creating intricate textiles with geometric patterns that often have spiritual meanings. They also craft silver jewelry, which serves as both adornment and status symbol, particularly for women.

In the late 15th century, the Inca Empire, under rulers like Pachacuti and Túpac Inca Yupanqui, sought to expand southward into Mapuche territory, but failed. The Mapuche fiercely resisted Inca attempts at domination through guerrilla tactics and their deep knowledge of the terrain, and the Incas after several expeditions, abandoned their attempts. The Maule River became a natural boundary, marking the southern limit of Inca expansion.

Starting about 50 years later, in the 1540s, the Spanish arrived in Mapuche territory in several waves under leaders like Pedro de Valdivia, seeking to conquer and colonise the land.

The Spanish did establish settlements, including Santiago and Concepción in Mapuche territory, but faced fierce resistance from them.

The Mapuche used guerrilla warfare to great effect, ambushing Spanish forces and retreating into forests and mountains. Lautaro, a former Spanish captive who learned Mapuche tactics and used this knowledge, helped them to lead successful uprisings against the Spanish, leading to a major victory at the Battle of Tucapel in 1553.

Very unusually for the European conquest of the Americas, in 1641, the Spanish signed the Treaty of Quilín, recognising the Mapuche’s independence south of the Bío Bío River. It would take more than two more centuries before, in the 1880’s, the Chilean government finally succeed in incorporating the Mapuche homeland into their territory, forcibly displacing a large part of the population.

Nowadays, efforts are underway to revive Mapudungun, traditional crafts, and Mapuche spiritual practices. Festivals like the We Tripantu (Mapuche New Year) celebrate their cultural heritage and connection to the land.

The Mapuche successfully resisted two powerful empires—the Incas and the Spanish—and have preserved many aspects of their culture despite centuries of oppression. They remain a symbol of cultural pride in Chile. Their connection to the land, spirituality, and identity serves as a testament to their strength and determination.

Santiago

Founded by the Spanish in distant 1541, nation’s capital doesn’t feel like a capital – it’s a bit sleepy, but easy-going, friendly and very relaxed. Some areas are reminiscent of Palermo in Buenos Aires. The majestic Andes are everywhere. And the food, based on Chile’s abundant seafood, is indeed excellent, with many fine restaurants.

Juan Fernández Islands

Uninhabited in pre-Columbian times, the Juan Fernández Islands were discovered by the Spanish in 1572 and have been occupied on and off since then.

They are a remote, rugged archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean, and nowadays belong to Chile.

The islands are volcanic in origin, characterized by steep, mountainous terrain, rocky cliffs, and lush green valleys. They are known for their unique ecosystem, beautiful landscapes, and rich history, particularly as the place where the sailor Alexander Selkirk was stranded, inspiring Daniel Defoe’s novel “Robinson Crusoe”.

The arrival of Europeans, brought significant environmental changes, much of which were detrimental. Here’s an overview of the main impacts:

Introduction of non-native animal species

- Goats: European sailors introduced goats as a source of food for future voyages. These goats multiplied rapidly and caused severe ecological damage by overgrazing, which led to soil erosion and the destruction of native plant species.

- Rats and Mice: Arriving along with humans, rodents were unintentionally introduced. They preyed on native birds’ eggs and competed with indigenous species for food, leading to a rapid decline in the number of indigenous bird species.

- Rabbits: Introduced later, they further exacerbated the problem of overgrazing.

- Feral Cats and Dogs: These were introduced later and further preyed on native birds and other small animals.

Deforestation

- Europeans cut down large areas of the islands’ forests for timber and to create space for agriculture. This deforestation led to the loss of native tree species, many of which were endemic to the islands.

Decline in native fauna and flora

- The introduction of invasive plants and animals led to the decline and, in some cases, extinction of native species. Many plant species unique to the islands were unable to compete with invasive species.

- Several bird species, including the Masafuera petrel and other ground-nesting birds, suffered due to predation by introduced species and habitat destruction.

Impact on Marine Ecosystems

- While the primary environmental damage occurred on land, overfishing and the introduction of non-native marine organisms by European ships also impacted the surrounding marine ecosystems.

Now a a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, the Juan Fernández Island are still a very valuable home to several rare animal species, including the fur seal, which was once nearly hunted to extinction, but has since made a comeback thanks to conservation efforts.

Selkirk Island

We visited the “Isla Afuera” (also called Selkirk Island), where now 42 people live for part of the year, fishing lobsters and enjoying their time “with no government control”, as one of the islanders told us full of pride. And, you know, we have a school too, he added. We were too shy to ask how many children attended it!

The nearest island to the “Isla Afuera”, appropriately called “Isla Adentro” since it’s “only” 650 km away from Chile’s mainland(!), is 9 hours away by fast boat. The other boats take a lot longer, but anyway no one ever shows up here, so it doesn’t really matter, the fisherman we spoke to said, with a complicit smile.

Not fun to get sick around here, the man commented before we left. And added: happy to give you a lobster if you have some Tylenol, I have a terrible headache today!

Robinson Crusoe Island

In 1704 a British boat dumped an unruly sailor named Alexander Selkirk, with a few supplies, on an uninhabited island, hundreds of km away from the South American coast.

Selkirk managed to survive for 4 years before he was rescued by a passing ship. He provided the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s book, which has since become one of the world’s most iconic adventure novels.

We spent a memorable day visiting what is now called “Robinson Crusoe Island”, a beautiful lush paradise, where 900 happy people live.

When he was finally rescued, Selkirk left the island with mixed feelings – he was overjoyed to see humans again, but sad to leave an island he had gotten accustomed to, and which had provided him, so he said, with a huge opportunity for personal growth.

Explora Hotel in Torres del Paine

We stayed in several hotels during our time in Chile. There is one that stood out – Explora in Torres del Paine.

It’s the only hotel in the Torres del Paine national park and it has its own catamaran. Explora also owns land in secluded areas, which you can only access if you stay there. The food is outstanding, the view from you room breathtaking, but the best part are the excursions, conducted by excellent guides who are all perfectly bilingual. It’s not cheap, but it’s definitely worth it!

We left Chile with a sense that we had not seen enough. And that our time there, two weeks, was much too short. Many coastal areas offer magnificent sites to discover and then, of course, the magnificent Andes are a source of inspiration and awe, a region we only scratched the surface of. We will be back!