Tibet is unlike anywhere else in the world — it’s often called the “Roof of the World,” but that barely scratches the surface of what makes it so special as a travel destination.

Tibet is one of the last places religion (in this case Buddhism) permeates everyday life. Monasteries are not museums — they are full of chanting monks, incense, and daily rituals. It’s a place where thousands of pilgrims prostrate themselves at all hours of the day and night, around sacred sites like the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa— not as a show, but as a profound spiritual act.

And places like the Potala Palace (former seat of the Dalai Lamas), Tashilhunpo Monastery, and Sera Monastery are stunning both artistically and spiritually. They’re not just beautiful, they are living relics.

But Tibet is more than culturally and spirituality amazing, it also offers amazing natural landscapes. The Himalayas, crowned by Everest, are right there. Places like Yamrok Lake and Namtso Lake shimmer turquoise at dizzying altitudes, surrounded by snowy peaks. And stretching endlessly under a massive sky, the Tibetan Plateau gives you a sense of scale and isolation found almost nowhere else.

Despite increasing modern infrastructure, Tibet still feels cut off from the modern world. Villages, monasteries, and nomadic camps survive in much the same way as they have for centuries.

Life rhythms in Tibet are dictated by ancient calendars, seasons, and religious festivals. It’s not a place where history is a background, it’s alive. Tibetans’ faith permeates everything: spinning prayer wheels, chanting under their breath, building cairns, offering prayer flags to the wind. It’s a place where you are surrounded by a palpable sense of spiritual energy.

Tibet is not an easy place to visit: the combination of thin air (Lhasa is over 3,600 meters) and intense light, sharpens emotions. Colors seem brighter, thoughts more reflective. And headaches/difficulties with sleep are very common, especially during the first few days.

Lhasa and surroundings

Lhasa and its surroundings are the soul of Tibet — a crossroads of spirituality, history, culture, and stunning natural beauty.

Built in the 7th century by King Songtsen Gampo, Jokhang Temple is the holiest temple for Tibetan Buddhists. Day and night, pilgrims walk the Barkhor Circuit (the sacred kora path around the temple), spinning prayer wheels, chanting mantras, and even circling the temple by prostrating themselves.

Once the winter residence of the Dalai Lamas, Potala Palace is a massive fortress-like structure rising dramatically above the city. Inside are thousands of rooms with intricate murals, ancient scriptures, and the golden tomb stupas of past Dalai Lamas. It’s not just beautiful, it reminds of Tibet’s impressive former size and spiritual identity.

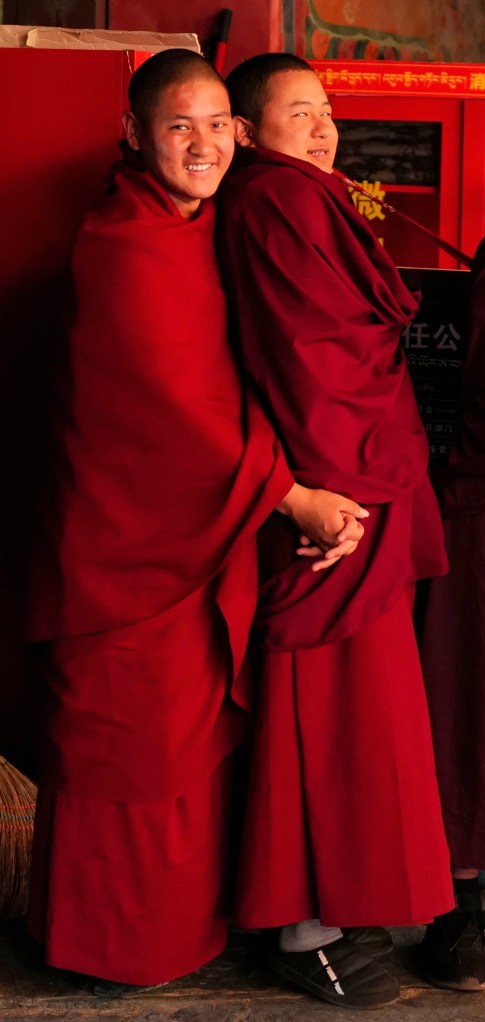

Sera and Drepung monasteries were once two of the largest monasteries in the world, home to thousands of monks. Even today, at Sera you can watch more than 600 monks energetically debate Buddhist philosophy, clapping their hands to emphasise points — it’s an incredible, vivid experience.

Wandering the Barkhor Circuit feels like stepping back centuries — narrow alleys lined with traditional Tibetan homes, prayer flags fluttering, shops selling butter lamps, incense, and handmade crafts. It’s here that you really feel the pulse of everyday Tibetan life.

Founded by Tsongkhapa (the initiator of the “Yellow Hat” sect, out of which emerged the Dalai Lamas), Ganden Monastery is perched dramatically on a mountain ridge about 1.5 hours from Lhasa. Walking the pilgrimage circuit around Ganden gives breathtaking views of the valley and offers a glimpse into true monastic devotion.

Pabongka is one of the oldest and most sacred sites around Lhasa — but it’s still relatively little visited compared to places like the Potala Palace or Sera Monastery. If you want a deeper, quieter encounter with Tibetan spirituality and history, Pabonka is extraordinary. Unlike the grand and crowded monasteries in central Lhasa, Pabonka feels raw, ancient, and intimate. You can hear the wind whispering among the prayer flags, and you might find a few monks or pilgrims — but very few tourists.

Bason Tso Lake and surroundings

Unlike Lhasa with its arid surroundings, the Bason Tso Lake and surroundings are nestled in a lush valley surrounded by snow-capped peaks, deep green forests, and pristine meadows. It’s an area aptly called “little Switzerland” for its alpine beauty. We spent two beautiful days there, enjoying quiet walks and visiting villages, like Tsongo, which are completely sheltered from tourism.

Samye Monastery

Founded in the 8th century, Samye Monastery is one of the most important and historically significant religious sites in Tibet.

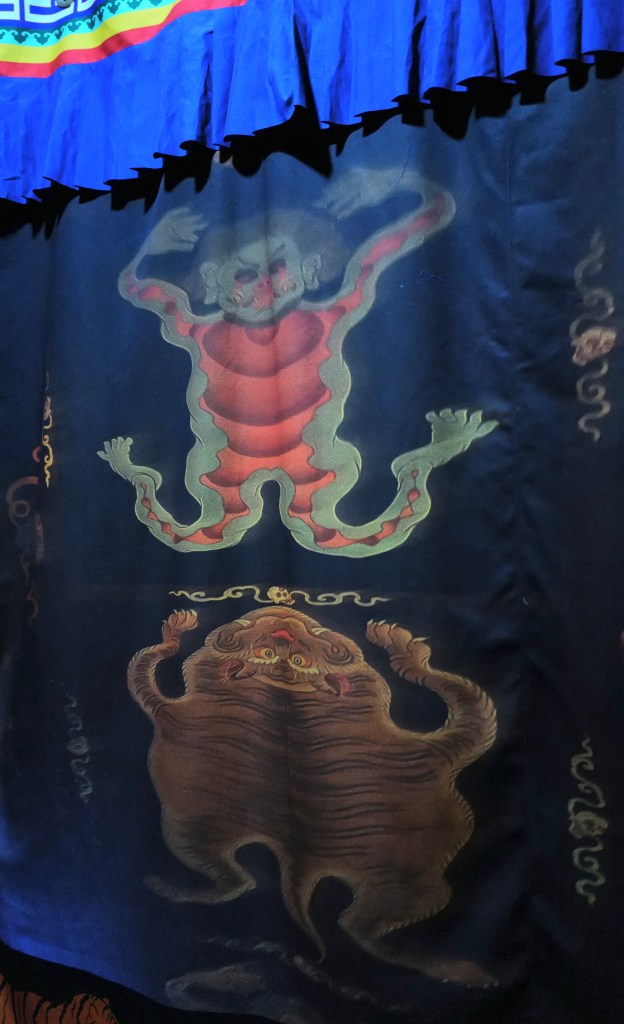

Samye was built as Tibet’s first Buddhist monastery with fully ordained monks. It symbolised the official introduction of organised Buddhism into Tibet, transitioning Tibet from its indigenous Bon religion towards Mahayana Buddhism.

Samye is designed as a giant three-dimensional mandala, representing the Buddhist vision of the universe. The central main temple symbolizes Mount Meru (the cosmic mountain at the center of the universe).

The main temple incorporates a mix of Indian, Tibetan, and Chinese styles — reflecting Tibet’s position as a crossroads of different civilisations.

Today, Samye feels deeply spiritual but also alive — a place where historical memory and active faith coexist.

Chimbu Nunnery & meditation hermitage

Chimbu is located north of Samye Monastery, up in the mountains that rise behind the flat valley where Samye lies.

It’s a rugged, beautiful area full of caves, small retreat houses, and meditation cells scattered across the hillsides.

Chimbu Nunnery itself is a small, modest community of Tibetan nuns who live and practice here year-round.

Life is extremely simple and ascetic here: no luxuries, basic living conditions, deep dedication to meditation, chanting, and ritual practice.

Spread across the steep hills are hundreds of hermitages and caves used for solitary retreats. Some are natural caves where a mat, butter lamp, and a few ritual implements are all that exist. Others are tiny stone huts or small temples built into the rock.

Many practitioners — both historical and modern — stay in strict retreat here for months or even years, following traditional three-year retreat programs.

The entire area feels profoundly sacred, isolated, and energised.

You hear the sound of wind over rocks, the flapping of prayer flags, and sometimes chants carried faintly through the air. Pilgrims and hermits coexist here in respectful silence.

As we wandered around, we were suddenly invited to visit the dwelling of a nun who said she has spent “many decades” (she was not able to be more precise) in solitary retreat here. We wondered how the life she has led would be for people like us, accustomed as we are to constant movement and new experiences…

Yamrok Lake

At 4’500m, Yamrok Lake is one of the three great sacred lakes of Tibet, along with Namtso and Manasarovar. In Tibetan belief, Yamdrok Lake is considered a living entity, the lifeforce of Tibet. It’s said that if the lake were ever to dry up, Tibet would no longer be habitable.

Many Tibetans perform pilgrimages (kora) around the lake, which take several days on foot. As for us, we had to cut short a hike, when we were surprised by a sudden snowfall.

The intertwined roots of Bon and Tibetan Buddhism

Buddhism arrived in Tibet around the 7th century, but before that, the region was home to the Bon religion. Bon, pronounced “Pen” or “Pon” in Tibetan, is considered the original philosophy and belief system of the Tibetan people. It dates back approximately 4,000 years and has significantly influenced Tibetan culture and Buddhism.

Bon was not a monolithic religion; it had various forms, including the original Bon, black Bon, colorful Bon, and white Bon. These forms differed in their rituals and practices, with some involving animal sacrifices. However, around 3,980 years ago, a figure named Tempa Shenrab, often compared to Buddha in Buddhism, revolutionized Bon. He unified its traditions and shifted the focus from sacrifices to philosophical teachings.

Bon’s influence on Tibetan Buddhism

Today, about 95% of Tibetans follow Tibetan Buddhism, but Bon’s influence remains profound. One of the most visible examples is the use of prayer flags. These flags, adorned with five colors—blue, white, red, green, and yellow—represent natural elements: sky, clouds, fire, water, and earth. This practice, rooted in Bon, symbolizes the interconnectedness between humans and nature.

Another significant influence is the incorporation of Bon deities into Tibetan Buddhism. For instance, the snow mountain deity Nianjen Thangla and the god Yalashambo, who rides a white yak, are originally Bon gods. Tibetan Buddhism also adopted many rituals and offerings from Bon, such as the use of incense made from juniper and other highland plants.

Rituals and practices

Bon rituals were deeply connected to nature, with gods representing various natural elements like the sky, mountains, earth, trees, and water. Initially, these rituals involved animal sacrifices, but Tempa Shenrab abolished this practice, emphasising philosophical and spiritual teachings instead.

In modern Tibetan Buddhism, many rituals and offerings, such as the Tibetan New Year celebrations, have Bon origins. For example, the offerings of Cemar (barley flour and butter) and Tirka (roasted wheat) are traditional Bon practices adapted into Buddhist ceremonies.

Bon monasteries today

Despite the dominance of Tibetan Buddhism, Bon still has a presence in Tibet. There are five to six Bon monasteries, primarily located around Lhasa, Northern, and Eastern Tibet. These monasteries maintain their unique deities and traditions, distinct from those in Buddhism. For instance, while Buddhists walk clockwise around stupas and temples, Bon practitioners walk counterclockwise.

The philosophical connection

The philosophical similarities between Bon and Tibetan Buddhism are striking. Both emphasize non-violence, meditation, prostrations, and prayers. The oral teachings and scriptures of both religions share many commonalities, though they differ in the names of deities and specific practices.

The seamless integration of Bon traditions into Buddhism highlights the adaptability and richness of Tibetan spiritual practices. For travellers seeking to immerse themselves in the cultural and spiritual heritage of Tibet, exploring both Bon and Tibetan Buddhism provides a more comprehensive and enriching experience.

The evolution of Tibetan Buddhism and the situation today.

The introduction of Tibet in the 7th century, during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo, called “the Great”, marked the beginning of a cultural and spiritual transformation in this nations, which at the time was almost as big as mainland China.

To consolidate his power, the king married two princesses—one from Nepal and another from China—who brought with them Buddhist statues and teachings. These statues were enshrined in two famous temples in Lhasa: the Jokhang Temple and the Ramoche Temple. These temples, along with twelve other “permanent temples” built across Tibet, laid the foundation for Buddhism in the region.

At this early stage, Buddhism in Tibet was more about the physical presence of statues and stupas rather than the historical Buddha’s teachings or the monastic community. It wasn’t until about 100 years later, in the 8th century, during the reign of King Trisong Detsen, that Buddhism truly began to take root. The king invited Indian masters, including Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita, to establish the first monastery in Tibet—Samye Monastery. This marked the beginning of a structured monastic system, with the translation of Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit and Pali into Tibetan playing a crucial role in spreading the Buddha’s teachings.

The development of different Buddhist sects

Over the centuries, Tibetan Buddhism evolved into several distinct schools, each with its own practices and traditions. The earliest school, known as the Nyingma school, emerged in the 8th century and is often referred to as the “Red Hat” school. The Nyingma tradition emphasizes both monastic and lay practitioners, allowing individuals to follow the path of Buddhism without necessarily becoming monks.

In the 11th century, new schools began to emerge. The Kagyu school, which originated in southern Tibet, was founded by Tibetan translators who traveled to India to receive teachings and empowerments. The Sakya school, which developed in western Tibet, was established by the Khon family, who invited Indian masters to teach in Tibet. Another significant school, the Kadam school, was founded by the Indian master Atisha and later evolved into the Gelug school, also known as the “Yellow Hat” school.

The Gelug school, founded in the 15th century by Tsongkhapa, became one of the most influential schools in Tibetan Buddhism. It is based on the Kadam tradition and emphasizes rigorous study and monastic discipline. The leaders of the Gelug school eventually became the Dalai Lamas, who not only held spiritual authority but also political power in Tibet from the 17th century until 1959.

Tibetan Buddhism today

Today, Buddhism remains a central part of Tibetan life. The vast majority of Tibetans consider themselves Buddhist, and the practice of Buddhism is deeply woven into the fabric of society. Monasteries and temples are not only places of worship but also centers of learning, where monks and nuns study Buddhist philosophy, medicine, and astrology.

One of the most striking aspects of contemporary Tibetan Buddhism is the active participation of laypeople. Despite economic challenges, many Tibetans regularly visit far-away monasteries to make offerings, receive blessings, and seek guidance from monks and lamas. The younger generation, while increasingly exposed to modern influences, continues to engage with Buddhism, often through digital platforms that provide access to teachings and rituals.

The government has played a key role in restoring and preserving many of the region’s historic temples and monasteries. While the government does not actively encourage religious practice, it allows for freedom of belief, enabling Tibetans to continue their spiritual traditions. This has led to a resurgence of interest in Buddhism, particularly as economic conditions have improved, allowing people more time to focus on spiritual pursuits.

The role of monks and nuns in today’s Tibetan society

Monks and nuns hold a revered position in Tibetan society. They are seen as teachers and spiritual guides, and many laypeople turn to them for advice on both spiritual and practical matters. Monasteries often serve as community centers, offering not only religious instruction but also advice on traditional Tibetan medicine and astrological services.

The relationship between monks and laypeople is one of mutual support. While monks and nuns traditionally rely on donations from the community, some larger monasteries have adapted to modern times by offering educational and medical services. This has helped to maintain the relevance of monastic institutions in contemporary Tibetan society.

Buddhism in Tibet is a living tradition that continues to evolve while staying deeply rooted in its historical and cultural context.

As you plan your journey to Tibet, take the time to explore its rich spiritual heritage. The teachings of Buddhism, the devotion of its practitioners, and the beauty of its sacred sites will surely leave a lasting impression, offering a deeper understanding of what it means to live a life guided by compassion, simplicity and wisdom.

Exploring Tibetan culinary traditions: past and present

Historically, Tibetan cuisine was heavily influenced by the nomadic lifestyle of its people. Animal husbandry, particularly the rearing of yaks, formed the backbone of their diet. Yak meat, a staple, was consumed in various forms—cooked, air-dried, or cured. In the absence of modern refrigeration, air-drying was a practical method to preserve meat for the long winter months. This cured meat, often eaten raw or used in soups, remains a traditional delicacy.

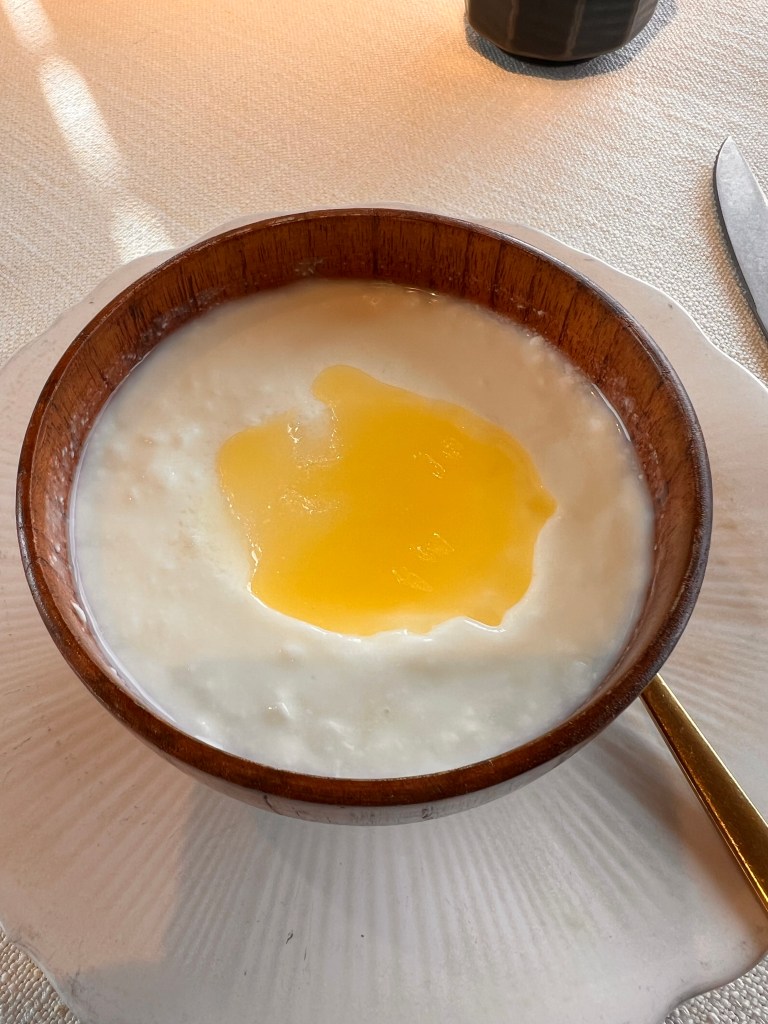

Another cornerstone of Tibetan cuisine is tsampa, a roasted barley flour. Barley, particularly highland barley, thrives in Tibet’s high-altitude environment. Tsampa is often mixed with yak butter tea, creating a hearty and nutritious meal. This combination has sustained Tibetans for generations, providing essential energy in the cold, rugged terrain.

Tibetans traditionally avoided eating fish and young animals like lambs. This practice stems from Buddhist principles, which emphasise minimizing harm to sentient beings. Eating larger animals like yaks, which could feed a family for a year, was seen as more ethical than consuming smaller creatures like fish, which required multiple lives for a single meal.

Seasonal and root vegetables

Given the limited growing season, Tibetans relied on root vegetables like potatoes and radishes, which could be stored in underground pits during winter. These vegetables were often pickled or dried to extend their shelf life. Wild greens, such as nettles, were also foraged and used in soups or dried for winter use.

Dairy products, particularly cheese and yogurt, played a significant role in the Tibetan diet. Cheese was made in various forms—sweet, sour, or dried—and often used in soups or as a topping for tsampa. Yogurt, best produced in the summer months, was celebrated during the Shoton Festival, a monastic event that has become synonymous with yogurt offerings.

Spices and flavours

Traditional Tibetan cuisine was not heavily spiced but relied on natural flavors and a few key ingredients. Salt, sourced from the mountains, was a staple, while wild onions and garlic added depth to dishes. Chilies, though not native to Tibet, were introduced via trade with Sichuan and India, becoming a popular addition to many meals.

Modern Tibetan cuisine: a blend of influences

Today, Tibetan cuisine has evolved, influenced by neighboring regions and global trends. Sichuan-style hot pots, for instance, have been adapted into Tibetan versions, using yak bone broth as a base. Similarly, the introduction of greenhouses has made it possible to grow a wider variety of vegetables year-round, expanding the culinary repertoire.

Despite these changes, most Tibetans continue to cherish their traditional foods. At home, families mainly prepare authentic dishes using ingredients sourced from the countryside, such as yak meat, barley, and homemade cheese. This commitment to tradition ensures that the essence of Tibetan cuisine remains alive. We experienced this during a family dinner were invited to in a traditional home close to Lhasa—the (mostly homegrown) food was simple, but delicious (especially the potatoes, probably the best we’ve ever had, and the yak milk tea).

Exploring the differences between Han and Tibetan people

During a dinner in Lhasa, we had the opportunity to sit down with two friends—a young lady from Shanghai who has recently settled in Tibet and a gentleman from Lhasa. They spoke to us about the differences between Han (the main Chinese ethnic group) and Tibetan people.

Living environments and social dynamics

One of the first topics we discussed was the difference in living environments. Our friend from Tibet shared that life in Lhasa feels more relaxed compared to the fast-paced lifestyle he has witnessed while traveling in mainland China. “Here, we don’t have the same pressure to succeed or the stark economic differences you see in bigger cities like Shanghai, Beijing or Chengdu,” he explained. “Our economy is more balanced, and there’s a sense of community and trust among people.”

In Tibet, social interactions are more open and welcoming. “If I go to a tea house or coffee shop, even if I don’t know anyone, I can start a conversation and share tea with strangers,” he said. This contrasts with his experience in mainland China, where he often felt people were more guarded and less trusting. “I find it’s harder to connect with others in mainland China. People are more focused on their own lives and don’t always trust strangers.”

Inner peace vs. the strive for materialistic well-being.

Another key difference is the focus on inner peace versus material success. Our Tibetan friend emphasized that in Tibet, happiness is often tied to inner values rather than external achievements. “We want to improve our lives and become richer, but not at the cost of losing our soul,” he said. “In mainland China, especially in big cities, people are more materialistic. They’re willing to sacrifice their well-being to make money.”

Our friend from Shanghai echoed this sentiment. “People in Tibet have strong religious beliefs, which give them a sense of purpose and inner peace,” she said. “In Shanghai, many people don’t have that. They focus on getting better jobs, earning more money, and improving their social status, but they often neglect their emotional well-being.”

Work-life balance and pace of life

The pace of life in Tibet is noticeably slower than in mainland China. “People here do things more slowly, but they’re still focused and deliberate,” our Tibetan friend explained. “In Shanghai, everything is fast-paced. People are always rushing, and there’s little time for relaxation or reflection.”

Our friend from Shanghai shared her personal experience of working in a high-pressure environment. “I used to teach at a prestigious private school in Shanghai, and I had to teach 33 hours a week. It was exhausting, and I often got sick,” she said. “Since moving to Tibet, I’ve felt healthier and more relaxed. The slower pace of life suits me better.”

Trust and community

Trust and community are central to life in Tibet. “Here, people trust each other more,” our Tibetan friend said. “If I want to help someone, they’re more likely to accept my help. In mainland China, people are more skeptical, and it’s harder to build trust.”

Our friend from Shanghai agreed, noting that in Tibet, people are more open and supportive. “I feel more connected to the community here,” she said. “In Shanghai, people are more focused on their own lives and less willing to share their thoughts and feelings.”

Cultural values and traditions

The conversation also touched on the importance of cultural values and traditions. Our Tibetan friend shared that in Tibet, people take pride in their heritage and feel a responsibility to preserve and promote their culture. “I work in tourism because I love my job and want to share our culture with others,” he said. “In mainland China, many people doing my job might think that’s foolish. They’re more focused on advancing their careers. They see tourism as just another way of making money and are not so interested in the intrinsic value of spreading their nation’s culture.”

Our friend from Shanghai added that in Tibet, people are more in touch with their inner selves and less concerned with external judgments. “Here, people are more focused on what makes them happy rather than what others think of them,” she said. “In Shanghai, there’s a lot of pressure to conform to societal expectations.”

Our long dinner-time conversation highlighted the profound cultural differences between Han and Tibetan people. While both communities have their strengths and challenges, the slower pace of life, focus on inner peace, and strong sense of community in Tibet offer a refreshing contrast to the fast-paced, materialistic lifestyle in mainland China.

As our friend from Tibet aptly put it, “Every culture has its positives and negatives. If you want one thing, you have to be willing to pay the price for it.” This balance between tradition and modernity, inner peace and material success, is what makes the cultural landscape of Tibet so fascinating and worth exploring.

Exploring the Tibetan language: origins, evolution and contemporary challenges

Tibetan is part of the Sino-Tibetan language family, which includes a variety of languages spoken across Asia. Its closest relative is Burmese. For example, the word “mi” in Tibetan, which means “human,” is similar to the Burmese word “myu.” This example highlights the shared heritage of these two cultures.

The Tibetan language is divided into several regional accents. These include the Western Tibetan accent, spoken in areas like Baltistan and Ladakh, the Southern accent, spoken near the borders of Bhutan and Sikkim, the Central accent (Uke), spoken in Lhasa, and the Northern accent (Horkie), which has similarities to the Mongolian accent. Despite these regional variations, the written language remains consistent across Tibet and all Tibetans, regardless of where they live, can understand each other.

The evolution of the written language

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Tibetan language is the stability of its written form. Inscriptions in monasteries and from the 7th and 8th centuries are still readable today, a testament to the language’s enduring nature.

The Tibetan alphabet consists of 30 letters, which are combined to form words and sentences. Unlike Chinese, which uses thousands of individual characters, Tibetan is more akin to Western languages with its alphabetic system. The language is also tonal, with four distinct tones that can change the meaning of a word. This tonal aspect adds another layer of complexity, but also beauty to the language.

Contemporary challenges and preservation efforts

At present, the Tibetan language faces several challenges, particularly in the face of globalisation and the influence of Chinese culture. While Tibetan children are taught Tibetan, Chinese, and English in schools, the prevalence of Chinese-language media and technology has led to a shift in language use among the younger generations. Many Tibetan children are more inclined to speak Chinese, especially when engaging with social media and digital content.

However, the people we spoke with remain optimistic about the future of the Tibetan language. They believe that as children grow older, they will come to appreciate the importance of preserving their linguistic heritage. Efforts are also being made at both the local and national levels to encourage the preservation of Tibetan and other ethnic languages. For example, there are Tibetan TV stations that broadcast in both Tibetan and Chinese, providing a platform for the language to thrive.