Yunnan is one of China’s most diverse provinces, often described as a microcosm of China itself. It’s special because it fuses geographic drama, ethnic diversity, ancient culture, and mild weather into a very special travel experience.

From the tropical jungles of the south to the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas in the northwest, Yunnan lies at the meeting point of three major biogeographical regions: the Himalayas, the Indo-Burma forests, and the subtropics of China. Thanks to its elevation, much of Yunnan enjoys a “perpetual spring” climate—never too hot, never too cold, even when other parts of China are sweltering or freezing. This makes it a choice destination for Chinese tourists, who constitute more than 98% of Yunnan’s tourism (you very rarely see foreigners).

No other Chinese province has more recognized ethnic minorities than Yunnan—53 out of China’s 56, including:

- Bai: known for refined architecture and white-walled homes.

- Naxi: rich musical and shamanistic traditions, centered in Lijiang.

- Yi: with their distinctive bimo priesthood and New Year fire festivals.

- Hani, Dai, Tibetan, and Mosso: each with unique languages, festivals, and clothing.

Yunnan is also full of ancient towns, and it is the birthplace of tea, with amazing varieties, such as the worldwide famous pu-er. Last but not least, local cuisines are deliciously spicy, earthy, and infused with herbs, mushrooms (esp. wild morels and matsutake) and pickled vegetables.

We spent 9 days in north Yunnan, which left us longing for more, since travel is very easy in China – the infrastructure is super modern, with excellent roads to even the most remote places, and trains are fast and of excellent quality.

Yunnan’s cities are clean and well kept, and the people are very friendly. We were often asked to pose with the locals and in one case we were asked to stay longer in a teahouse to await the arrival of the owner’s niece, who “absolutely wants a photo with a foreigner”.

Few people speak English, but everyone in China has a smartphone equipped with a translator, so conversations are slow, but not a problem.

Dali

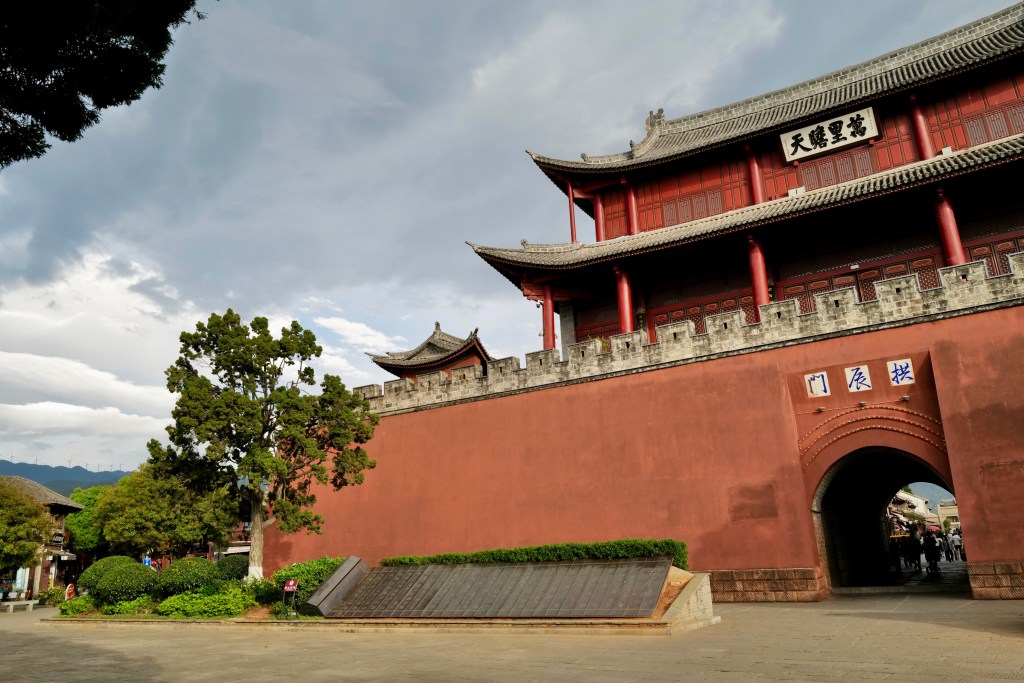

Protected from bandits and invaders by 6-meter-deep stone walls, Dali was once an important outpost on trade routes that spanned Tibet and Southeast Asia and has been the centre of the Bai peoples’ universe for more than a thousand years.

Today, Dali is a cultural and geographic jewel of Yunnan, a place where the essence of southwest China’s beauty, diversity, and depth all converge.

What makes Dali and its surroundings so special is a fusion of Bai heritage, dramatic landscape, and a long history as a crossroads of trade, migration, and ideas.

In the middle of Dali’s busy streets, is the “Russia friendship store”, stocked exclusively with Russian goods and accompanied by Russian traditional music.

To the west of Dali rises Cangshan mountain, a collection of 3,500m peaks which offer epic views of the town and the lake sprawling through the valley below. The Jade Cloud Road, a paved and sometimes precipitous walkway, leads high up the mountain, past waterfalls and secluded temples, offering a respite from the hustle and bustle of Dali

Just 70 km from Dali is Weibaoshan, a sacred mountain dotted with ancient Taoist temples. The hike up and down is quite steep and about 8 km long, ensuring that few tourists venture here. We loved the beautiful sites and the quiet spirituality of this magnificent area.

Shaxi

Shaxi was once a vital stop along the ancient Tea Horse Road — the trade route connecting China to Tibet and beyond. Tea was transported to Yunnan, whose population in return received Himalayan salt from Tibet, without which large populations would have been impossible in Yunnan, which has no salt mines.

As a result, Shaxi became a cosmopolitan trade hub, with inns, stables, caravanserais, and temples serving travelers from across the Himalayas and China.

Shaxi has been beautifully restored is one of the last surviving market towns along this trade route still in its original layout.

Weibaoshan sacred mountain

Weibaoshan, also known as Weibao Mountain, is a revered Taoist mountain situated about an hour from Dali. It is recognised as one of China’s 13 sacred Taoist mountains, and esteemed for its historical, spiritual, and cultural significance. The mountain is home to over 20 Taoist temples, many dating back to the Ming and Qing dynasties.

We loved the silence (there are very few tourists, since you need to walk about 8 km up and down a steep hill), the temples and the beautiful views.

We had originally scheduled an appointment with the head of the Daoist temples in Weibaoshan, but he was “travelling” on the day we were there. We later learned that in Daoist tradition, a spontaneous decision to travel is intrinsic to a Daoist monk’s life and becomes a way to mirror The Dao’s movement, loosening rigid patterns of thought and identity. The Dao itself is described as flowing like water, never static, always adapting. In Zhuangzi’s words: “To be truly free is to wander.”

Weishan Village

Weishan is a preserved ancient town in western Yunnan province, China, located close to Dali. It’s often overshadowed by nearby Dali and Lijiang, which have seen more tourism development, but for those seeking authenticity, rich history, and a slower pace, Weishan is a hidden gem.

Weishan was the birthplace of the Nanzhao Kingdom, a powerful 8th-century kingdom that later formed the foundation of the Dali Kingdom. Before Dali became the capital, Weishan was the center of political and cultural life in the region.

The Bai Three Tea Ceremony: a journey through history and culture

Nestled in the heart of Yunnan, near the ancient city of Dali, lies a cultural treasure that has been passed down through generations—the Bai Three Tea Ceremony. This ritual, steeped in history and tradition, offers a unique glimpse into the lives and values of the Bai people.

The origins of the Bai Three Tea Ceremony trace back to the Tang Dynasty and the era of the Dali Kingdom. Historically, it was a ceremonial practice reserved for welcoming esteemed guests and dignitaries. Despite the Bai people having a spoken language without a written script, this tradition has been meticulously preserved through oral storytelling, ensuring its survival to this day.

In 2014, the ceremony was recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage, and in October 2022, it was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This acknowledgment underscores its significance as a living testament to Bai culture.

The Three Teas: A Reflection of Life

The ceremony, which we participated in, took place in the courtyard of the ancient home of a wealthy Bai merchant. It is structured around three distinct teas, each symbolizing a stage of human life:

1. The First Tea: Bitter

The journey begins with a simple yet profound brew—water and tea leaves, lightly roasted to enhance their aroma. This bitter tea represents the struggles and hard work that define the early stages of life.

2. The Second Tea: Sweet

The second tea introduces a delightful contrast, blending local walnuts, cheese, and brown sugar. This sweet concoction symbolizes the rewards and joys that come after perseverance, offering a taste of the good life.

3. The Third Tea: Memory

The final tea is a complex blend of ginger, herbs, pepper, and honey. Its numbing effect serves as a metaphor for reflecting on one’s life journey, evoking memories and lessons learned along the way.

Participating in the Bai Three Tea Ceremony is more than just sipping tea—it’s an immersive cultural experience. Each cup tells a story, inviting you to connect with the Bai people’s values, history, and way of life. It’s a reminder that every sip can be a journey, and every journey can leave a lasting memory.

Lijang

Lijiang is one of the most iconic and enchanting towns in Yunnan Province, known for its beautifully preserved old town, its rich Naxi cultural heritage, and its stunning natural surroundings, including the nearby Jade Dragon Snow Mountain. It sits at the crossroads of ancient trade routes—most notably the Tea Horse Road—and offers a blend of history, landscape, and ethnic diversity unlike anywhere else in China.

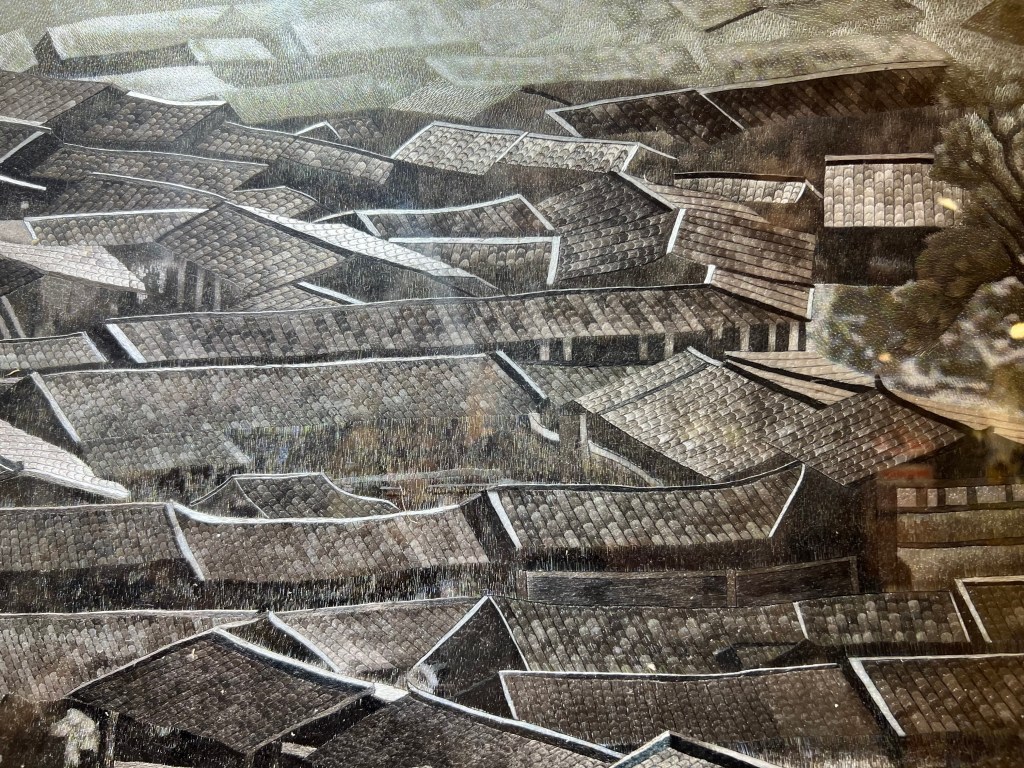

Today a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Lijiang Old Town is a maze of cobbled streets, canals, stone bridges, and traditional Naxi courtyard houses.

We spent 3 days in Lijang and its surrounding area, but it was much too short. If you can, spend at least 5 days in Lijang.

Stone Dragon Village

Stone Dragon Village is a small, culturally rich, and largely unspoiled village located in the Shaxi Valley, southwest of Dali and nestled between the Cangshan Mountains and the Mekong (Lancang) River watershed. It sits at the foot of Shibao Mountain , a site of great religious and historical significance. This makes Stone Dragon Village not only beautiful in its setting but also culturally layered and spiritually resonant.

After hearing traditional courting love songs of the Bai people, interpreted by the winner of last year’s Bai competition, we savoured a memorable meal prepared by Mrs. Chang, produced exclusively with local products.

Baisha Village

Baisha Village is a small, historically rich village located about 10 km north of Lijiang. It’s one of the oldest settlements of the Naxi people.

Baisha was the original capital of the Naxi Kingdom and the political and cultural heart of the region during the early Ming dynasty.

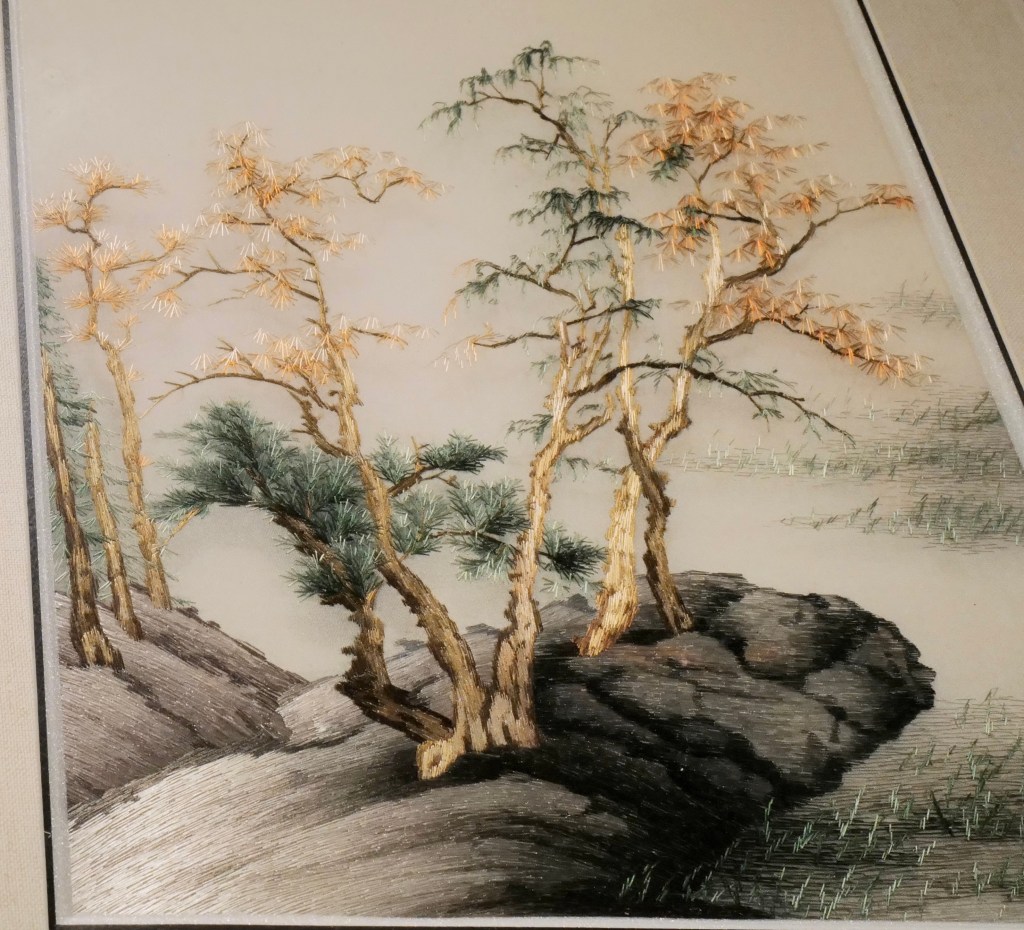

Baisha is known for traditional embroidery and weaving, where master artisans keep this intricate art alive. We saw this at the Baisha Embroidery Institute, one of the last two embroidery studios in Yunnan.

Wenhai Village and Yi spiritual beliefs

Wenhai sits at 3,100 meters above sea level, high above Lijiang, in a hidden alpine basin on the slopes of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

It lies within the Lashihai Nature Reserve, a UNESCO-protected area known for migratory birds, diverse flora, and highland forest ecosystems.

Trails around Wenhai are perfect for trekking, birdwatching, and cultural exploration, with old caravan paths linking it to Baisha and Yulong Mountain.

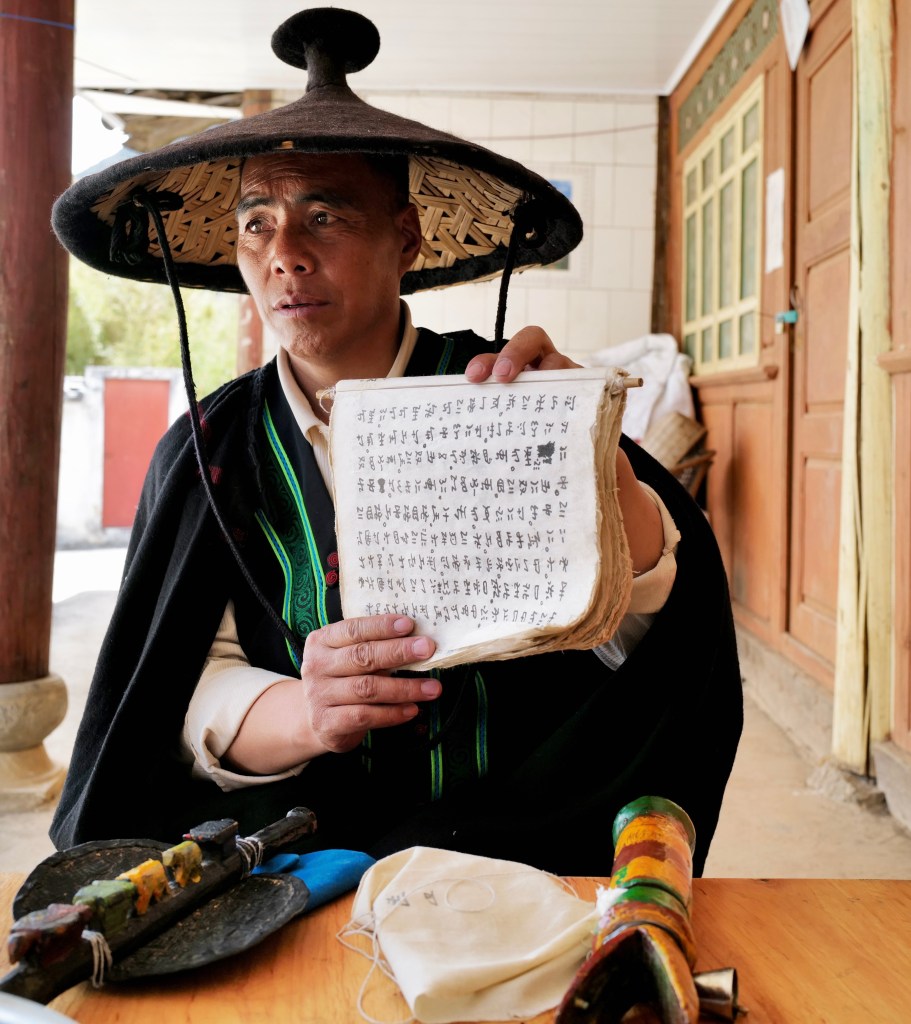

At Wenhai we met Mr. He, the local shaman, who the Yi people call Bimo. Mr. He performed a welcoming ceremony for us and acquainted us with the Yi people’s beliefs.

The Yi people are one of China’s largest ethnic minorities and have lived in the mountainous areas of Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou for many centuries. Their belief system is animist, ancestral, and shamanic, blending cosmology, ritual, and magic.

The Yi believe that the souls of ancestors remain active in the lives of the living. They are honoured through rituals and offerings, especially during festivals and major life events. Ancestral spirits can bless or harm, depending on whether they are properly venerated. Natural elements—mountains, rivers, trees, stones—are believed to have spirits or deities. Sacred groves and mountains are often off-limits to hunting or cutting wood. The Yi regard fire as particularly sacred: it is linked to warmth, ancestors, and purification.

Bimos, like Mr. He, are priest-scholars who perform rituals, heal the sick, and interpret ancient Yi texts written in their unique script. They conduct ceremonies for ancestor appeasement, curing illnesses, divination and exorcism, and agricultural fertility.

Bimoism is one of the only indigenous religions in China with its own written canon (written in Classical Yi script).

Yuhu village

Yuhu sits directly below the southern slope of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, making it one of the highest-altitude villages in the Lijiang region. The views are reminiscent of the Alps.

The village is built using unique stone-and-mud bricks called yuhu shi, a local volcanic rock, giving it a rustic and enduring architectural style. A lot of the town is currently in construction, in one year its reconstruction should be completed, making it even more appealing than today.

Shangri-la

Shangri-la was formerly known as Zhongdian. The name “Shangri-La” was adopted in 2001 from the fictional paradise described in James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, and the area was renamed to promote tourism—but it does have striking similarities to the novel’s setting.

Although in Yunnan province, at 3’200m Shanghai-la sits on the Tibetan plateau and is populated primarily by Tibetans.

The Tibetan culture here is rich and visible—in the architecture, religion, festivals, and daily life. Prayer flags are fluttering in the wind, and people are spinning prayer wheels, while yak butter lamps glow in ancient temples.

It’s a relaxed, welcoming town, surrounded by snowcapped peaks, alpine meadows, lakes, and forests.

Pu-er tea

Pu-er tea is one of the most celebrated and mysterious teas in the world. Deeply tied to Yunnan Province, it is the only Chinese tea with a true tradition of aging and fermentation, developing more complexity—and often higher value—over time, much like wine.

Considered to aid digestion, reduce cholesterol, and help with weight management in Chinese traditional medicine, it is known as a “tea for after heavy meals” due to its grease-cutting effect. In Chinese folklore, it has been called “tea for emperors” and “tea that ages with wisdom.”

The trees used to produce pu-er tea are central to its identity. Unlike most other Chinese teas, which are typically made from small-leaf tea bushes, pu-er is made from the large-leaf variety collected from tall trees. This leads to a distinctive bold, full-bodied flavour, as well as excellent suitability for fermentation and long-term aging.

Yunnan’s ancient tea forests are national treasures. Many are now protected or semi-wild, with harvests done by ethnic minority families (Hani, Bulang, Dai, Lahu).

Pu-er tea is categorised not just by the region or fermentation process, but by the age and growth method of the tea trees.

High-quality pu-er from famous mountains or centuries-old trees is collectible and can appreciate in value with age. We had the good fortune of tasting in Lijang at Fuxinchang Teas some of the most celebrated pu-er varieties Yunnan produces, some stemming from trees that are over 1000 years old and have been aged for more than 25 years.

There are two varieties of pu-er teas:

Fermented (or ripe) pu-er

- Microorganisms (yeasts, bacteria) transform the tea over 40–60 days.

- Results in a dark, earthy, mellow tea ready to drink shortly after production.

- Similar in flavor to very old raw pu-er, but usually rounder and less dynamic.

- Keeps for about 30 years, with the best time to consume between 20 to 30 years.

Unfermented (or raw) pu-er

- Unfermented when young — technically like a green tea.

- Ages naturally over years or decades, developing microbial fermentation slowly.

- Gains depth and earthy complexity with age.

- Keeps for about 70 years, with the best taste after 30 years.

Great pu-er’s have an unbelievable complexity, comparable to great wines. They are not cheap, but the best ones are worth the cost.

Exploring Naxi Culture: Calligraphy, Religion, and Tradition

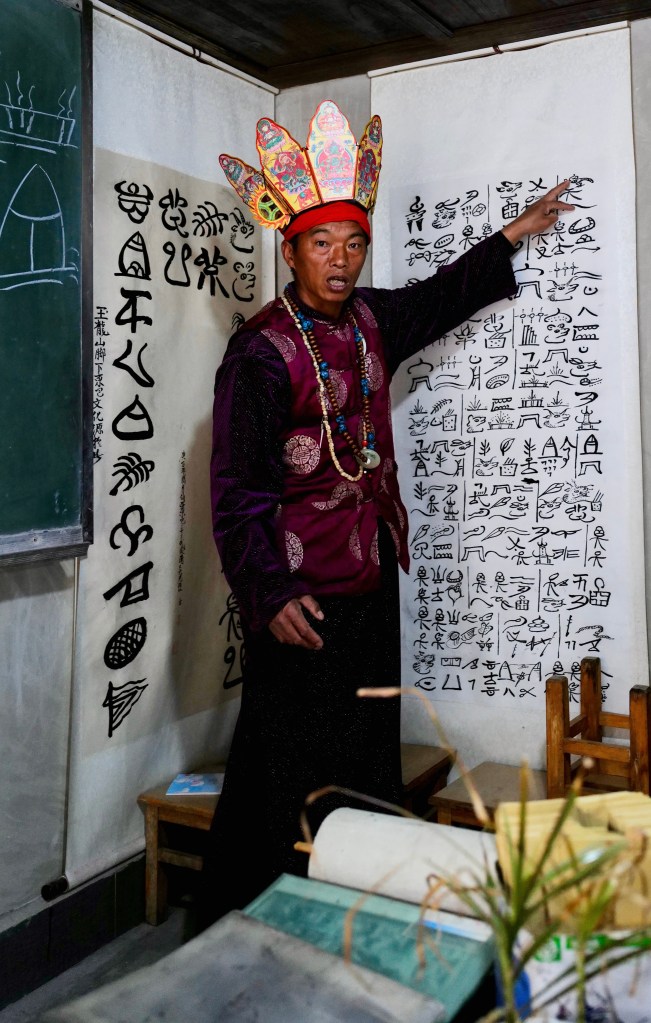

During our journey to Lijiang, we had the privilege of delving into the rich cultural heritage of the Naxi people, particularly their unique Dongba religion and ancient calligraphy. This experience offered us a profound understanding of their traditions, beliefs, and the efforts to preserve their culture in the modern world.

The Dongba Religion and Its Priests

We visited the home of Mr. He, a Dongba priest, who is the 34th generation in his family to carry on this sacred role. The Dongba are not just religious figures but also teachers, doctors, and spiritual guides for the Naxi community. Unlike the Bimo religion of the Yi people, which we explored the previous day, the Dongba religion worships a pantheon of gods, including mountain gods, river gods, and the revered Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, known as Bim.

The Dongba priests use an ancient script, the last pictographic script remaining in the world, to record their scriptures. This calligraphy, passed down from father to son, is a living testament to a culture that dates back over 3,000 years.

The Role of Joseph Rock

We learned about Joseph Rock, an American-Austrian explorer who documented the Naxi culture extensively between 1922 and 1949. His work became invaluable after many artifacts and scriptures were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Some of the oldest scriptures, dating back 320 and 470 years, were preserved by local families and later restored with the help of Rock’s records.

In 2008, the Dongba scriptures were recognized as a UNESCO Memory of the World Heritage. These texts cover various aspects of life, from worshiping ancestors and natural gods to conducting ceremonies for the deceased. The Naxi believe that after death, the spirit must return to their ancestral homeland near the Yellow River to be reborn.

The Philosophy of Harmony with Nature

The Naxi people’s deep respect for nature is evident in their worship of gods of nature. They believe in maintaining a harmonious relationship with the environment, a philosophy that resonates with many indigenous cultures worldwide. For instance, they avoid cutting ancient trees or polluting water sources, viewing these actions as disrespectful to the spirits that inhabit them.

Preserving a Unique Culture

Despite the challenges of modernization, the Naxi people are determined to preserve their culture. Mr. He, for example, teaches the Dongba script and religious practices to young villagers, ensuring that this ancient knowledge is not lost. The Chinese government’s recent support for minority cultures has also played a crucial role in this preservation effort.

Our visit to Mr. He’s home was a humbling reminder of the importance of cultural preservation. The Naxi people’s dedication to their traditions, despite historical adversities, is inspiring. This experience was not just a journey through the Naxi culture but also a lesson in the resilience and beauty of human heritage.

Reflections on Life in Lijiang: a journey through Chinese recent history and change

During our time in Lijiang, we had the privilege of having dinner at the home of Mrs. Sao, who prepared a delicious meal, primarily based on her garden’s vegetables, using only a wok as a cooking instrument for everything she served. Her simple home, was nevertheless incredibly warm and welcoming, full of flowers and colourful plants.

After dinner, we had time to speak with Mrs. Sao, who shared her life story, offering a unique perspective on China’s history and the profound changes she has witnessed over the decades.

Born in 1951, she grew up in Lijiang and experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand. Her narrative provides a window into a transformative period in China’s history and the resilience of its people.

Life during the Cultural Revolution

In the late 1960s, as a young woman of 19, she was sent to a small village called Shiku, north of Lijiang, as part of the government’s initiative to encourage urban youth to contribute to rural development. Along with four classmates, she lived with a farming family, sharing their daily life and labor. While they cooked and ate separately, they worked alongside the farmers, applying their knowledge to tasks like farming, construction, and raising pigs.

She described this time as challenging yet fulfilling. Despite the lack of material comforts, the community spirit was strong. Villagers supported one another, sharing food and resources when needed. She recalled feeling mentally enriched, even if life was physically demanding.

After three years in Shiku, she returned to Lijiang and was offered a teaching position, a testament to her education and the scarcity of qualified teachers at the time. She later attended university, studying a broad range of subjects, and continued her career as a teacher, instructing students in Chinese, math, music, and physical education.

Reflections on Change

Looking back, she described her life as a series of distinct periods, each with its own challenges and rewards. During her youth, material goods were scarce, but life was simple and community bonds were stronger. Today, she enjoys the comforts of modern life, including retirement benefits and access to healthcare, but she acknowledges the increased pressures and competition faced by younger generations.

When asked if she would prefer China as it was then or as it is now, she hesitated, emphasizing that societal progress is inevitable. She views her experiences as part of a larger historical journey, one that has shaped her and her country in profound ways.

A Glimpse into the Red Guards

As a former member of the Red Guards, Mrs. Sao offered a nuanced perspective on this often-misunderstood group. While Western narratives often focus on their more extreme actions, she emphasized that her experience was different. In Lijiang, a smaller and at the time more remote city, the Red Guards’ activities were less intense, and she did not witness or participate in the violence often associated with them.

A Journey Through Time

Mrs. Sao’s story is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the Chinese people. As we left, we felt grateful for the opportunity to learn from her firsthand account. Her reflections remind us that travel is not just about seeing new places but also about understanding the lives and stories of the people who call those places home.

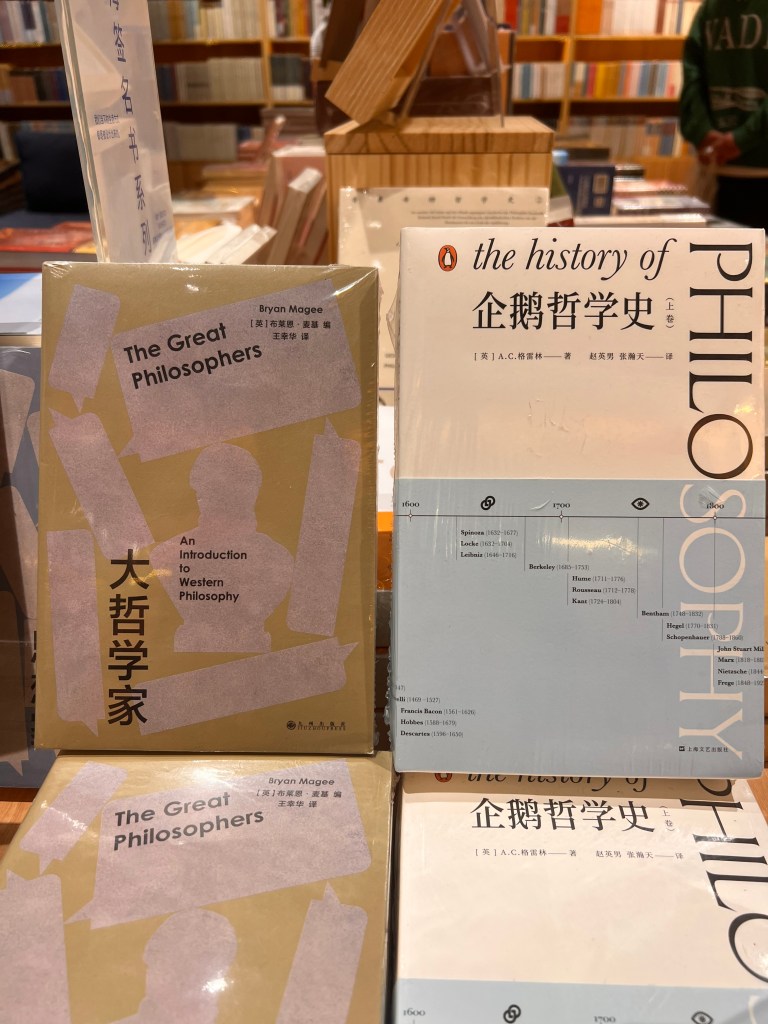

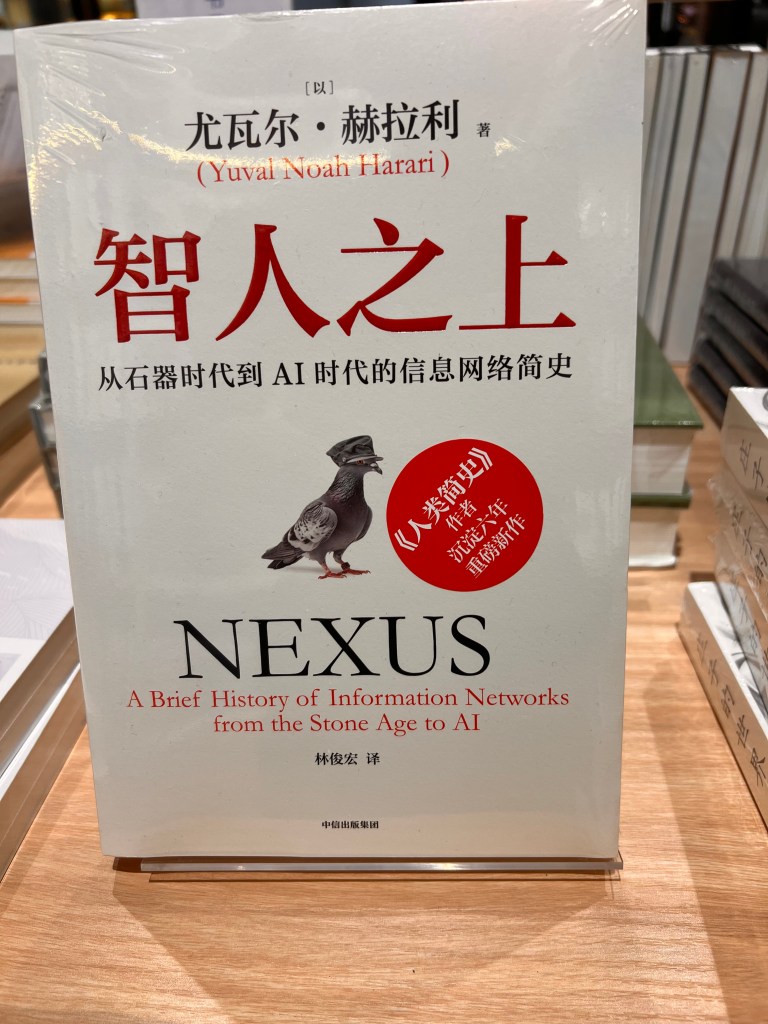

Mrs. Sao’s reflections, however, offer only one view of the Cultural Revolution. For other views, make sure you read “Wild Swans” or “Mao” by Jung Chang or “My way out of Gobi” by Weijan Shan.

Exploring the matriarchal society of the Mosso people

Nestled around the serene Lugu Lake in the north of Lichang, Yunnan, the Mosso people are one of the last matriarchal societies in the world. With a population of around 25,000, the Mosso have preserved a unique way of life that continues to fascinate scholars and travelers alike.

A matriarchal society

In Mosso culture, the family is led by the oldest woman, often referred to as “grandmother.” She holds authority over family decisions, including finances and daily tasks. All family members contribute their earnings to the grandmother, who manages the household budget. This system fosters a sense of unity and minimizes conflicts, as there is no individual ownership of money or property.

The Walking Marriage

One of the most distinctive aspects of Mosso culture is their practice of “walking marriage.” Unlike traditional marriages, Mosso couples do not live together. Instead, men visit their partners at night and return to their own homes before daybreak. Children born from these unions belong to the mother’s family and are raised by her relatives. The biological father’s role is minimal, as the children consider their maternal uncles as their male role figures.

This system eliminates many of the challenges faced in conventional marriages, such as disputes over property or child custody. If a couple separates, the children remain with the mother, and there is no shared property to divide.

Family dynamics

The Mosso family structure is deeply rooted in the maternal line. Families live in large courtyards, with the grandmother’s house at the center. Each evening, family members gather around the fireplace in the grandmother’s home to share meals, stories, and warmth. This communal living strengthens familial bonds and ensures that everyone feels supported.

Gender roles and relationships

In Mosso society, women hold significant power, especially in choosing their partners. During festivals and ceremonies, women and men meet and form relationships. The women typically initiate these unions, with both parties expected to remain monogamous during the relationship, which often spans a lifetime. If a couple decides to part ways, the process is handled respectfully, often with the involvement of family elders.

Religion and daily life

The Mosso people practice Tibetan Buddhism, specifically the Gaji Pai branch, which emphasizes kindness and moral behavior. Temples are central to their spiritual life, and families often have their own small shrines for daily prayers. This religious framework influences the Mosso people’s daily actions, encouraging harmony and compassion within the community.

Interaction with other communities

The Mosso live peacefully alongside other ethnic groups in the area surrounding the Lugu Lake, including the Yi, Tibetan, Han, and Lisu people. While intermarriage is rare, the Mosso maintain friendly relations with their neighbors. The Chinese government has also taken steps to preserve Mosso culture, encouraging families to teach their language to the next generation and by improving infrastructure in their villages.

Challenges and adaptations

While the Mosso way of life has endured for centuries, modern influences pose challenges. Many Mosso individuals who marry outside their community struggle to adapt to their new nuclear family structure, which often leads to divorce. Divorced Mosso people generally return to their homeland, where they are reintegrated without questions.

Visiting the Mosso offers a rare opportunity to witness a matriarchal society in action. From their unique marriage customs to their communal family structure, the Mosso provide valuable insights into alternative ways of organizing society. Their emphasis on love, respect, and harmony serves as a reminder of the diverse possibilities for human relationships and community living.

If you’re a traveler seeking to understand cultures that challenge conventional norms, the Mosso people of Lugu Lake are a must-visit destination. Their way of life is not only a testament to resilience but also a source of inspiration for building more inclusive and harmonious societies.

Politics

We arrived in Yunnan in the middle of April 2025, a few weeks after a trade war between China and the US seriously escalated.

How did people we met react? Everyone we spoke to was relaxed, believing that China will come out stronger out of this situation. “Chinese people are industrious and can take hardship. High tariffs with the US gives China an opportunity to become less reliant on other countries, which in the long term is good for the country”, we heard all the time.

Everyone we spoke to rallied behind their government, feeling that short-term difficulties would be “no problem”. Others told us they believed that China will have the upper hand because “we can take hardship, whereas Americans will not support their president for long if they don’t get results quickly”. The US administration will have to backtrack, so the Chinese feel that time is in their side. In other words, they are in no urgency to negotiate.

The people we met think that Americans will suffer more than them because Americans are addicted to high quality, low cost products coming from China, and that if the try to produce the same in the US, they will not succeed because Americans want to be paid more and are less industrious, so the result will be inflation and less good products.

They also think that US famers will lose disproportionately because they will not be able to export to China any more. As an example, US farmers have been selling billions of chicken feet to Chinese consumers, who consider them a delicacy. With the high tariffs that China just introduced, US farmers will be stuck with them, so the US administration will come under severe pressure in states that have traditionally been red.

Overall, what we saw in China is an industrious, modern, peaceful, very friendly and well organised society. The urban infrastructure is excellent and the communication system (including trains and roads) is amazing, more impressive than in most industrialised countries.

There is no question that, overall, the Chinese people (including the minorities) are deeply grateful to their government for the progress the country has made over the last three decades. Perhaps some civil liberties that we take for granted in the West are curtailed, but this does not appear to be a problem for most Chinese. The Chinese people we met spoke to us freely and their appreciation for the government was sincere. They also made it clear that criticism of the government is tolerated in private, less so in public, but once again, this is not seen as a major problem.

China is definitely not a police state, in fact we never saw a policeman during our entire stay in Yunnan. And it’s also not a country where crime is prevalent – the shops we saw were completely open, it would have been very easy to steal!

The people of China

Probably because very few foreigners visit China (more than 98% of China’s tourism is internal), people were curious and eager to meet us – we were stopped many times on the street with questions of where we came from and very often people asked to take photos with us.

We made friends spontaneously on trains or just by walking around, with many Chinese offering to connect with us on WeChat. We leave Yunnan with a very warm feeling and thankful for the wonderful reception its people have offered us!