A great traveller once said that if you have the time and the means, there really are only two places to visit: Japan and the rest of the world.

It’s certainly true that the beauty of Japan’s countryside, the uniqueness of its minimalist architecture, its stunning urban gardens, its gorgeous temples and shrines, the refined food, the impeccable cleanliness, the perfectly on-time trains, the country’s incredible arts & crafts and the magnificent shops, make it an amazing place to fall in love with.

But not everything is beautiful in Japan, in fact most of the country has been butchered by nonsensical constructions and bright neon lights. And beyond what you see is also how you feel, and here Japan can get very difficult — the population’s frigid rigidity behind the veil of extreme politeness, and the (mostly absurd and totally inflexible) rules and regulations its people impose on everyone and everything, make it very challenging for a visitor to feel truly welcome.

We spent four packed and eventful weeks on an “off the beaten track” tour of southern Japan, which included a bit of time in cities such as Kyoto and Osaka, but mostly in the countryside, in places like Kameaoka, Setoda, Utazu, the Iya Valley and Naoshima, which not many foreigners visit. This allowed us to see “another Japan”, and what we saw disappointed, at times even frightened us.

Rather than concentrating on a detailed itinerary, we have chosen to focus this travel report on a few subjects that spoke to us. But which ever way you choose to visit or look at Japan, there is no doubt that it’s a country that will not leave you indifferent. It is, without doubt, one of the world’s most interesting countries to spend time in, even if, as in our case, there are parts you might want to forget about.

The origins of contemporary Japanese society

The origins of Japanese society, as we know it today, can be traced back to the rise of the samurai (warrior class) at the end of the XIIth century. The samurai ruled Japan, not just through 700 years of direct political control, but especially by instilling a code of conduct, values, and an aesthetic sensibility that permeate society to this today. Though Japan today is a modern, pacifist, democratic nation, the warrior past continues to shape how Japanese people think about duty, honour, discipline and identity.

During the Heian period (794 to 1185 CE), Japan was a court-dominated society modelled after Chinese ideals —elegant, aristocratic, and religiously infused. The imperial court was ruled by powerful noble families, particularly the Fujiwara clan, who dominated politics through strategic marriages and regencies.

The elite lived in elegance, deeply invested in court rituals, poetry, art, and romantic literature. As the court grew increasingly insulated and focused on aesthetics, it neglected governance. Local government fell to provincial nobles and warrior bands hired to protect estates. These warriors—called samurai—developed their own codes, alliances, and armed forces. Initially subordinate to noble patrons, they gradually gained land, wealth, and independent power. By the 11th and 12th centuries, disputes between aristocratic factions began to be settled by force, with the samurai doing the fighting. This gave the samurai more and more power.

In 1192 AD, the emperor granted Yoritomo, a samurai, the title of Sei-i Taishōgun (barbarian-subduing generalissimo), formalising the first shogunate (military government) in Kamakura. This marked the beginning of true samurai rule. Although the emperor remained the nominal sovereign, real power shifted to the military class. From this point forward, Japan was ruled by samurai governments for nearly 700 years—until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

The Meiji Restoration meant the end of the samurai, but by no means the end of Japan’s stiff, asphyxiating rules-dominated society. Successes in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) gave the military enormous prestige and influence in foreign and domestic affairs. The samurai were formally abolished, but their ethos was repurposed for the nation-state and the emperor.

By the early 20th century, Japan became one of the world’s most militarised nations. Civilian government weakened in the 1920s and 1930s due to economic crises and political instability. Military officers assassinated political opponents, and ultranationalist ideologies surged.

Japan’s military formally dominated politics by the 1930s, often acting without civilian oversight. Under military rule, Japan expanded into Manchuria (1931) and later launched a full-scale war in China (1937), culminating in World War II. By 1942, Japan occupied and ran most of Asia with an iron grip. The behavior of Japanese forces in the countries they occupied during World War II was marked by brutality, repression, and widespread atrocities.

While Japan since 1945 has become pacifist and democratic, it still exhibits a highly regimented, disciplined, and rules-oriented society—which feels thoroughly militaristic in tone and structure. This isn’t military control per se—rather, it reflects a deep cultural continuity of hierarchical discipline, conformity, and order that is just the continuation of what the samurai put in place starting in the XIIth century.

In practice, since 1945, Japanese companies have become like mini-armies, with lifetime employment mirroring lifelong military service. Salarymen even today wear uniforms (dark blue suits), work in strict hierarchies, and show lifelong loyalty to their company. Employees even participate in regular group exercises and chant company slogans, echoing prewar national mobilisation.

Meanwhile, schools emphasise group behaviour over individualism, cleanliness, uniformity and etiquette, and insist on strict rules on hair, clothes, and behaviour. These traits echo military regimentation but are presented nowadays as “moral and civic training”. It is out of the question to challenge or even question what teachers teach students in Japan. Schools, like families, stress acceptance and submission.

Nowadays Japan is not a militarised state in the Western sense—there’s no draft, and police aren’t heavily armed. But the country is tightly run by career bureaucrats, whose operating style is often opaque, procedural, and top-down. This produces an environment of approvals, often ridiculous and senseless rules, and strict formality.

So Japan’s contemporary its culture is all about order, hierarchy, and self-control, which is not very different to what the society was like under samurai feudalism and wartime mobilisation.

You will not feel much of this if you only visit Tokyo and Kyoto for a few days, stay in Western hotels and eat in expensive restaurants catering primarily to tourists. But you will be struck by the Japanese oppressive, rules-dominated society everywhere else you go.

Zen Buddhism and the rise of Japanese aesthetics

Zen’s great rise in Japanese society took place during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), in particular with Eisai (1141–1215), a Japanese monk who traveled to China and brought back Rinzai Zen. He emphasised meditation, accompanied by rituals like tea, making Zen palatable to the Japanese aristocracy, but especially to the growing and rising class of samurai warriors.

From the XIIth century onwards, as the aristocratic order declined and Japanese society became more militarised, Zen found natural allies in the samurai due to shared values:

- Discipline and focus: The samurai valued mental clarity and direct action — qualities cultivated by Zen meditation and koan practice.

- Instant enlightenment: Zen’s emphasis on instant enlightenment, which contrasted with the more gradual and cumbersome stages of spiritual development found in other forms of Buddhism spoke to the samurai, who had no interest in the courtly manners of the Japanese aristocracy and the complicated Mahayana Buddhist traditions. Zen’s focus on meditation, which could be practiced anywhere and at any time, also resonated with the samurai’s practical and disciplined nature.

- Minimalism and self-control: As a counterbalance to the opulence of earlier Heian court Buddhism, Zen emphasised austere temples, simple rituals, and silent practice — all resonant with the practical mindset of warriors.

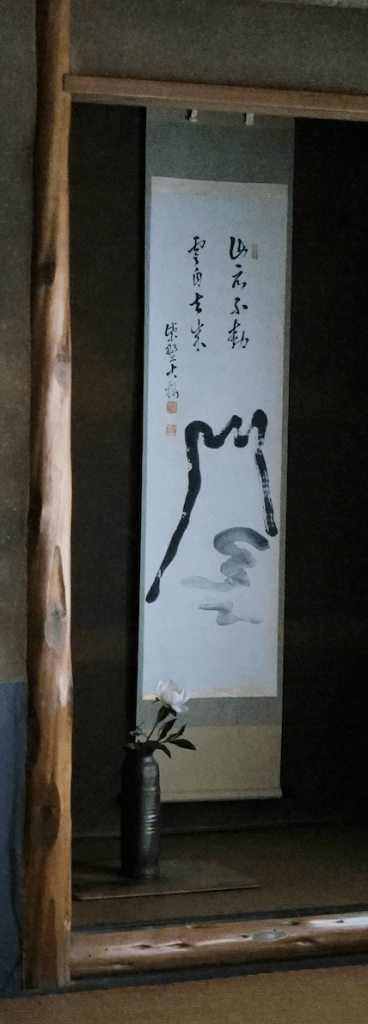

- Tea ceremony: Tea was initially introduced to Japan from China by Zen monks, in order to help them stay awake during long hours of meditation. As Zen spread from the temples to the samurai class, the tea ceremony evolved into a highly ritualised practice that embodied the principles of Zen, but also, with its detailed steps and codified rules, greatly spoke to the samurai’s sense of order. Tea houses, where the ceremony still takes place today, were designed to be austere, with minimal decoration. This simplicity is intentional, as it allows participants to focus on the experience of the tea itself rather than being distracted by ornate objects. A typical tea room might feature a single scroll with a bold, calligraphic message and a few flowers. The scroll often contains a Zen saying, the most famous of which is “Ichigo Ichie,” which means “One time, one meeting,” something the samurai would typically value. The tea ceremony also reflects Zen’s appreciation for simplicity and imperfection. The ceramic bowls and other tools used in the ceremony are often humble and unrefined, in contrast to the elaborate and ornate ceramics used by the court. This aesthetic, known as wabi-sabi, celebrates the beauty of the imperfect and the transient, which fits well with the samurai ethos (see section below on the Tea Ceremony).

- Calligraphy: the energetic, bold Zen calligraphy, which even today often reads like government slogans, gave an artistic conduit which suited the samurai’s worldview (see section on calligraphy below).

- Gardens: Zen-inspired strict rules governing gardens, their strongly tailored and manicured, often sterile environments, with rivers symbolised by pebbles and islands symbolised by rocks, worked perfectly for the control-minded samurai (see section on Japanese gardens below).

- Acceptance of death: Zen’s embrace of impermanence and letting go of the ego harmonised with the bushido code of readiness to die, which in the samurai time was put in practice via seppuku (ritual suicide) and during World War II through kamikaze pilots.

The appeal of Zen to the samurai class had a lasting impact on Japanese society. As the samurai rose to power, they brought with them the disciplined, rule-based approach of Zen, which permeated all aspects of Japanese life. This militaristic ethos, combined with Zen’s emphasis on mindfulness and simplicity, have to this day shaped Japanese society into a highly structured and methodical culture.

We had the unique opportunity to spend a morning with the Abbot of Kodaiji Temple in Kyoto, with whom we had a long conversation about Zen and its impact throughout the ages. This was followed by meditation and a tea ceremony on the temple’s premises (see section on the tea ceremony below).

The art of Ikebana: embracing nature and balance in Japanese flower arrangements

When traveling to Japan, one of the most profound cultural experiences you can immerse yourself in is the art of Ikebana, the traditional Japanese practice of flower arrangements. Ikebana is not merely about placing flowers in a vase; it is a disciplined art form that embodies harmony, balance, and a deep respect for nature.

Unlike Western flower arrangements, which often focus on symmetry and abundance, Ikebana emphasises asymmetry and minimalism. The Japanese sensibility values imperfection and irregularity, which is typically reflected in Zen- inspired art forms, including Ikebana.

One of the key principles of Ikebana is the use of odd numbers. In Japanese culture, odd numbers are considered auspicious, while even numbers are avoided because they can be divided, symbolising separation or discord. This is why Ikebana arrangements typically involve three, five, or seven elements.

Ikebana practitioners believe that every flower has a direction and a purpose. When arranging flowers, they carefully observe how the flowers grow in nature and strive to replicate it in their arrangements. For example, if a branch naturally curves to the left, the arranger will position it in a way that highlights this natural form.

This attention to detail extends to the choice of vessels as well. Ikebana arrangements are often placed in simple, understated containers made of materials like bamboo, ceramic, or woven reeds. The vessel is chosen to complement the flowers and enhance their natural beauty, rather than overshadow it.

In Japan, Ikebana is not just an art form, it is considered a way of life. It is very common to see Ikebana arrangements in homes, temples, hotels and shops. The practice is deeply intertwined with other aspects of Japanese culture, such as the Tea Ceremony and calligraphy.

For example, in a tea room, the Ikebana arrangement is often kept simple and understated, with a focus on creating a serene and calming atmosphere. White flowers are preferred for evening arrangements, as they stand out in the dim light, while red flowers are used during the day for their vibrant energy. And the flowers, if possible, are chosen to work in symbiosis with the message/calligraphy of the tea room scroll.

Ikebana is accessible to everyone, regardless of experience. While there are schools and teachers who can guide you, the essence of Ikebana lies in your own observation and intuition. As one Ikebana master put it, “The moment you pick a flower, you should already know how you want to arrange it”.

This emphasis on intuition and personal expression is what makes Ikebana so unique. It is not about following strict rules or achieving perfection; it is about finding your own connection to nature and expressing it through your arrangement.

Ikebana is more than just a flower arrangement, it is a reflection of Japanese aesthetics. The practice embodies the Japanese appreciation for simplicity, imperfection, and the transience of life.

Calligraphy

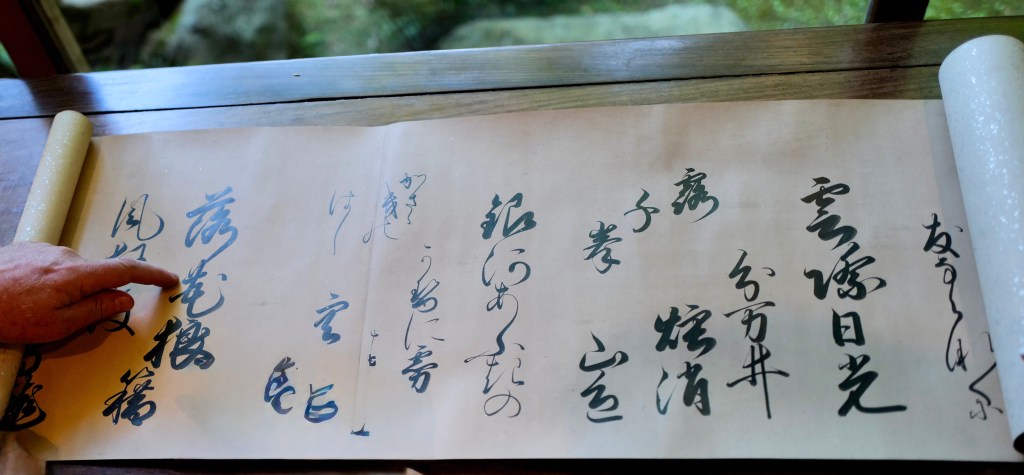

Japanese calligraphy, or shodo (“the way of writing”) spans over a millennium and can be loosely grouped into three historical and stylistic lineages, each reflecting a different facet of Japanese culture: imperial court elegance, Zen immediacy, and samurai governance.

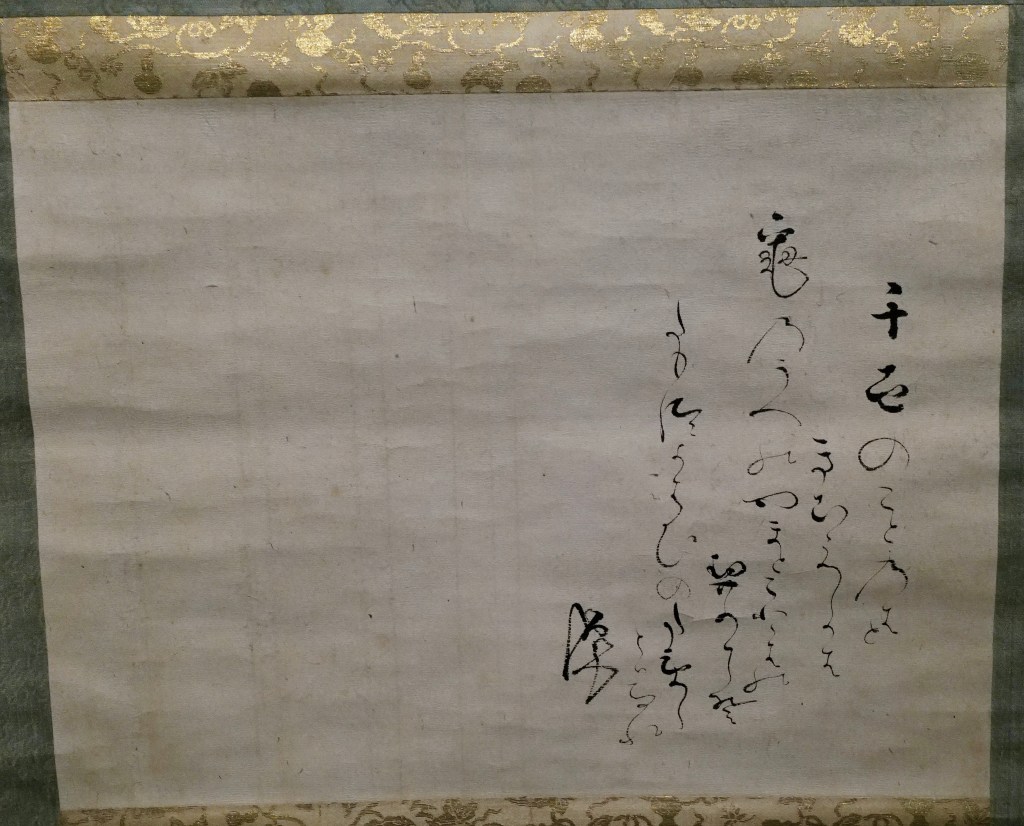

Courtly calligraphy was popular primarily in the Heian period (794–1185 AD). Elegant, flowing, ethereal, it is often associated with women of the court and literati like Sei Shonagon and Murasaki Shikibu. The emphasis is on grace, aesthetic restraint, and emotional nuance. Poetry (waka) was a common subject; the calligraphy itself was considered part of the artistic expression.

Zen calligraphy (bokuseki) was developed in the Kamakura to Muromachi eras (13th–15th centuries), but is still very much practiced today. Invented as a reaction to Courtly calligraphy, Zen includes bold, raw, spontaneous brushwork. It often features kanji characters only, sometimes a single character. It is expressive and gestural, bordering on abstraction.

In Zen calligraphy, the ink density, brush pressure, and movement become expressive tools beyond legibility. Deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism, bokuseki reflects satori (sudden enlightenment). The act of writing is itself seen as a moment of mindfulness, presence, and emptiness. The brush becomes a tool for spiritual expression, not just communication. Calligraphy here is not to be read so much as felt. There is beauty in imperfection — a strong parallel with wabi-sabi.

Samurai or bureaucratic calligraphy was used during the Kamakura and Edo periods (1185–1868 AD) and is based on Chinese formal styles. As the samurai class rose to power, calligraphy reflected a more austere, disciplined aesthetic. It was still an art form, but also a mark of education, authority, and moral character. Samurai calligraphy is strong, clear, balanced — a bridge between spiritual and practical. It was primarily used for official documents, records and military correspondence. It is more formal and rigid than Zen style, but more structured and legible than courtly calligraphy.

Tea

Tea holds a profound place in Japanese culture, not just as a drink but as a symbol of harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility. Its cultural role is deeply interwoven with aesthetics, philosophy, social rituals and, as we saw above, Zen Buddhism.

There are many types of Japanese tea. These are the most common:

- Bancha – A lower-grade green tea harvested later in the season. Sold with leaves and stems. Coarser and more astringent. Japan’s “everyday” tea.

- Sencha – The most common green tea, lightly steamed leaves with a fresh, grassy flavour. Comes in many varieties and has a beautiful, intense green colour.

- Hojicha – Roasted green tea with a toasty, earthy taste and low caffeine. Often served in the evening.

- Genmaicha – A mix of green tea and roasted brown rice. Nutty and mellow, smells a bit like popcorn.

- Gyokuro – A premium shade-grown green tea with a deep umami flavour. Highly prized and expensive. Difficult to brew properly, since it needs to be infused at low water temperatures (50° C).

- Matcha – Finely powdered green tea used in the tea ceremony. Strong, rich, and slightly bitter.

Japanese Tea Ceremony

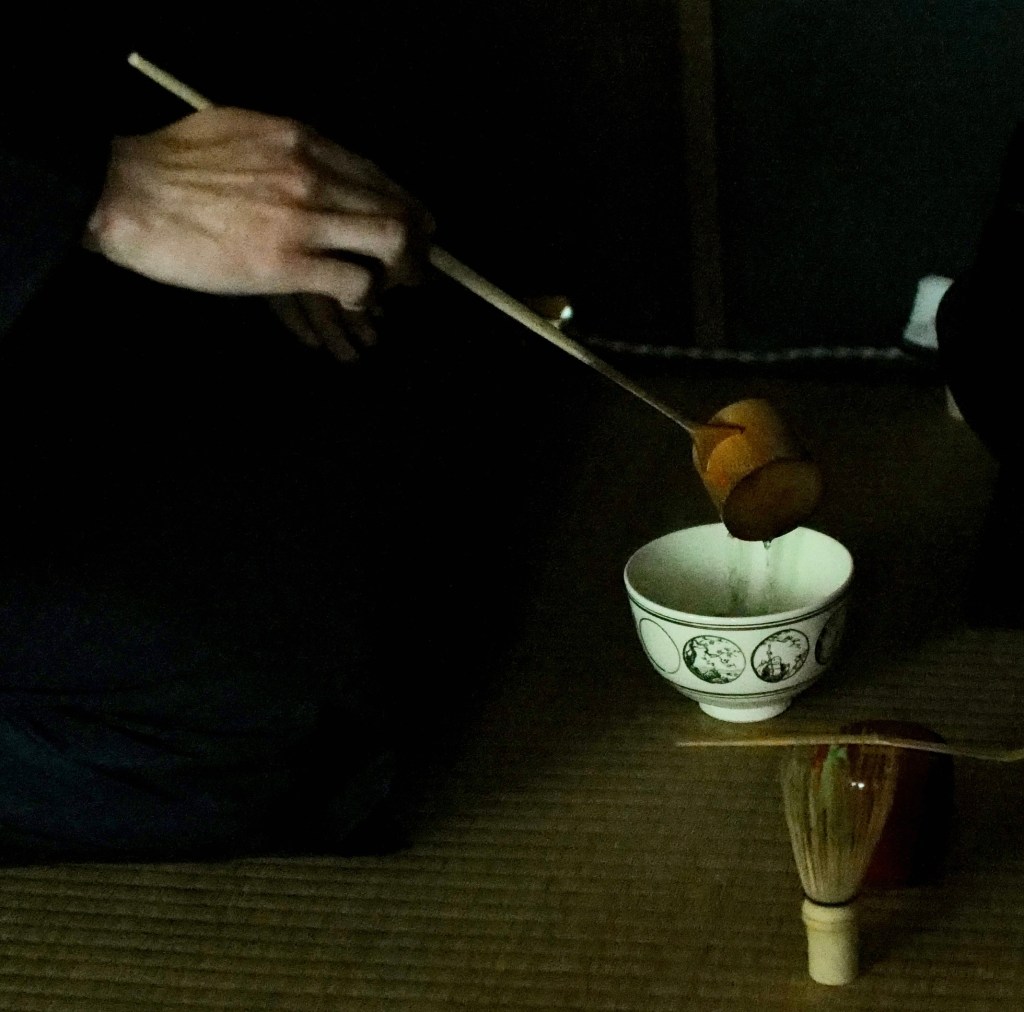

In Japan, the Tea Ceremony is not primarily about drinking tea, it’s a highly ritualised exercise, a spiritual and aesthetic experience rooted in Zen Buddhist values.

The ceremony, as we know it today, was introduced and ritualised by Sen no Rikyu in the 16th century. Its core principles are harmony, respect, purity and tranquility, messages that spoke very strongly, as we have seen, to the samurai.

The setting takes place in a purpose-built tea room or chashitsu, often reached by a simple garden path (roji) symbolising the journey inward. Everything from the tea bowl (chawan) to the whisk (chasen) and kettle (kama) is carefully chosen and admired in the Tea Ceremony. It varies by season and by the theme that the Tea Master wishes to instil into a particular ceremony. Every element—the scroll, the flowers, the sweets, even the choice of tea—is selected to reflected the season and a particular message that the Tea Master wishes to transmit to the people he’s invited.

The chasen is a traditional Japanese bamboo whisk used to prepare matcha in the Tea Ceremony. It’s an essential tool that reflects not only functional craftsmanship but also aesthetic and spiritual values rooted in Japanese culture.

Cultural significance

Tea and the Japanese way of life:

- Aesthetics: The Tea Ceremony emphasizes wabi-sabi—the beauty of simplicity and transience.

- Social Etiquette: Offering tea is a sign of hospitality. It’s served during visits, ceremonies, and in daily life.

- Zen Buddhism: The ritual and mindfulness of preparing and drinking tea echo Zen values. Many Tea Masters were originally Zen monks.

- Art and Architecture: Tea culture has influenced everything from ceramics and calligraphy to garden design and interior aesthetics.

- Philosophy and mindfulness: The deliberate pace and quiet rituals of tea drinking offer a counterbalance to the speed of modern life.

- Education and discipline: Learning the tea ceremony takes years of training, combining precision, humility, and attentiveness.

Japanese gardens

Japanese gardens are among the most refined and philosophically rich landscape traditions in the world. They are not merely decorative spaces, but carefully composed microcosms of nature infused with meaning, cultural symbolism, and emotional resonance. What makes Japanese gardens so special lies in their deep aesthetic principles, spiritual underpinnings, and deliberate use of space and time.

Aesthetic principles

Japanese gardens are guided by traditional aesthetic values that emphasize beauty in simplicity and imperfection:

- Wabi-sabi: The beauty of transience, imperfection, and rustic simplicity.

- Shibui: Subtle and unobtrusive beauty—restrained elegance.

- Yugen: A profound, mysterious sense of beauty beyond words.

These principles create a garden that is never flashy but deeply evocative.

Nature idealised

Japanese gardens idealize and mimic natural landscapes on a smaller scale:

- Miniaturisation: Mountains, rivers, and forests are suggested by using rocks, sand, moss, and trees.

- Asymmetry: Gardens avoid symmetry to reflect nature’s organic, unpredictable forms.

- Borrowed Scenery: Background elements like distant mountains or trees are explicitly visually integrated into the garden design.

Symbolism

Every element in a Japanese garden is purposeful and often symbolic:

- Stones: Represent islands, mountains, or stepping-stones on a spiritual path.

- Water: Symbolises purity, life, and impermanence. If not physically present, it may be suggested through raked gravel.

- Bridges: Transition points, often symbolising the journey from the earthly world to the spiritual one.

- Lanterns and Pagodas: Suggest timelessness and serve as focal points, often placed with intentional imbalance.

Types of gardens

Different types of Japanese gardens serve different purposes:

- Karesansui: Dry landscape or Zen garden—minimalist, with rocks and gravel raked to suggest water. Used for meditation.

- Chaniwa: Tea gardens—rustic and simple, designed as a path leading to a tea house. Emphasizes quiet introspection.

- Strolling gardens: Large gardens meant to be enjoyed while walking, with paths that reveal changing views and moods.

- Tsubo-niwa: Small courtyard gardens—tiny, often urban spaces that bring a pocket of nature into daily life.

Integration with architecture

Japanese gardens are often designed to be viewed from specific angles—through a veranda, tatami room, or temple window. The transition between inside and outside is seamless, inviting quiet contemplation.

Seasonality and change

Japanese gardens highlight seasonal change, encouraging the viewer to notice impermanence:

- Cherry blossoms in spring – beauty that fades quickly

- Maples in autumn – the poignancy of decline

- Snow on stone lanterns – silence and stillness

- Moss in rain – lushness and time’s passage

The garden is never static—it’s a dialogue with time.

Spiritual and philosophical depth

Rooted in Zen Buddhism, Shintoism, and Daoism, Japanese gardens often express:

- Harmony between humans and nature

- The transience of life

- A meditative path towards inner peace

Kabuki Theatre

Kabuki is a classical form of Japanese theatre known for its stylised drama, elaborate costumes, striking makeup, and highly codified performance. It’s both a traditional art form and a vivid spectacle that has fascinated audiences for over 400 years.

Kabuki means “the art of song and dance,” but it also implies the idea of being eccentric or unconventional—kabuku means “to lean” or “to deviate.”

Founded in Kyoto in the early 1600s, during the Edo period, it was nitially performed by women (onnagata), but female performers were banned in 1629 due to concerns over morality and prostitution. Young male actors (wakashū) replaced them, but they too were banned, so the art form evolved to be performed exclusively by adult men, a tradition that continues today.

Key features

- Elaborate Costumes: Bright, often exaggerated outfits that reflect the character’s role and status.

- Kumadori makeup: Bold, symbolic makeup for male roles, with colours indicating traits (e.g., red for heroism, blue for villainy).

- Mie pose: A dramatic pose held by actors at climactic moments to heighten emotion and signal importance.

- Hanamichi: A raised walkway extending into the audience, used for dramatic entrances and exits.

- Narration and music: Live music using traditional instruments like the shamisen, and narrative chanting from offstage or side-stage performers.

- All-Male casts: As mentioned above, male actors play both male and female roles, with female roles known as onnagata.

We spent an afternoon watching Kabuki in Tokyo and absolutely loved it. Even though we probably missed a lot of subtleties, we certainly got the main messages. The acting and costumes are so intense and vivid to make Kabuki an unforgettable experience.

Geisha

The word geisha literally means “art person” or “artist.” A geisha is essentially a performer and hostess, skilled in the traditional arts of Japan — especially dance, music (shamisen, koto, flute), singing, and poetry, as well as the art of conversation and hospitality.

One of the most persistent myths is that geishas are sex workers. They are not. Geishas are highly respected cultural professionals.

It takes about 5 years for a maiko (apprentice) to become a geisha (called geiko in Kyoto). The training is hard and involves making compromises that many young women in Japan are unwilling to make (for example, no access to mobile phones during the years of training, having to attend all functions decided by the Geisha house in which they live, etc.). Accordingly, there are fewer young women becoming geishas, which has created a shortage, at a time when the tourist industry has prompted a strong demand for geisha events.

We participated in a rare event held at the home Alex Kerr in Kameoka, about 30 minutes from Kyoto. The setting was perfect for an intimate dinner, followed by magnificent dancing by a geisha. and a maiko. An older geisha played music to accompany the dancing. It was a beautiful evening.

Scarecrow village

Like many rural villages across the world, Nagoro progressively lost its inhabitants, until only 10 or so were left in what was before a prosperous village of 300 people.

Saddened by this loss, starting in 2002, Tsunami Ayano (one of the few remaining inhabitants) decided to bring the village to life again by featuring many of its former inhabitants in the form of scarecrows.

A visit to Nagoro today offers a haunting, but also a humorous and certainly a striking reminder of the effects of rural exodus.

Shinto: honouring the divine in Nature

Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, emphasises the sacredness of nature and the presence of kami , or deities, in all aspects of life. Central to Shinto rituals is the honden or main shrine, where the goshintai or sacred object representing the deity, is enshrined. This object can take various forms, such as a mirror, a sphere, or a small shrine, symbolising the divine presence. Often there is no object of devotion at all, the shrine just shows an empty altar or a closed altar door, the shrine emodying the “spirit” of the kami (or of all kamis).

Offerings such as vegetables, fruits, rice, and water are placed on the altar as a gesture of gratitude to the earth and the deities. These offerings symbolise the interconnectedness of all life and the importance of giving back to the natural world.

Fire and evergreen plants, such as pine, are also integral to Shinto rituals. Pine, believed to be the first plant to emerge on Earth, is revered for its resilience and vitality. By offering these elements, practitioners honor the life-giving forces of nature and seek to maintain harmony with the environment.

Purification and renewal: the essence of Shinto

A defining feature of Shinto is the emphasis on purification, or harae. This practice involves cleansing the body and mind of impurities, much like brushing one’s teeth or taking a bath. By purifying oneself, individuals can ward off illness, negative influences, and misfortune, paving the way for happiness and peace.

The act of purification is often accompanied by the use of haraigushi, a wand adorned with paper streamers, which is waved to dispel negative energies. This ritual serves as a reminder of the importance of maintaining cleanliness and balance in all aspects of life, both physically and spiritually.

A universal message of harmony

Shinto’s teachings resonate with people around the world, as they emphasise the unity of all religions and the shared roots of spiritual wisdom. Whether it is the Christian God, the Buddha, or Allah, Shinto recognises these deities as manifestations of the same universal source. This inclusive perspective fosters a sense of global harmony and mutual respect among different cultures and faiths. It is therefore not uncommon in Shinto shrines to find Buddhist deities.

Why are Japanese shops so discreet?

Those of us who have grown up in the West are accustomed to windows of shops shouting their offerings at passersby: “Today, 30% discount on selected merchandise”, “Just arrived – new collection”, “Black Friday specials”, etc.

By contrast, Japanese shops are muted. Sometimes it’s even difficult to know from the outside what is sold inside a shop, or even that there is a shop inside.

Where does this come from?

Japanese aesthetics often value subtlety, modesty, and suggestion over loudness or clarity. This ties into concepts like:

- Wabi-sabi — finding beauty in imperfection and the understated.

- Shibui — a kind of refined, quiet elegance.

Rather than shouting what they sell, Japanese shopkeepers prefer to invite curiosity, rewarding the observant or the returning visitor. The experience is meant to generate discovery, not to reward reaction to advertising.

In Japan, there’s a deep-rooted cultural value in not intruding or imposing. Just as homes typically don’t show off their interiors, many shops adopt a similar approach. This is especially true of places like tea houses, crafts boutiques, or high-end restaurants, which may want to filter for clientele who understand or appreciate subtle clues. If a shop has no signs, or a very minimal presence, it may be signaling that it’s meant for people “in the know.”

The result in a quite muted and uniform streetscape, where it’s not immediately obvious what’s what — unless of course you’re looking closely.

The beauty of Japan

There are many beautiful sights to be seen in Japan. It’s a country that (especially if you visit the immaculately kept temples and their surrounding gardens) lends itself to sublime photos. Here are a few, from the many we took while traveling throughout the country.

This is Japan too: a surprisingly ugly urban and environmental landscape

Traveling through Japan makes you wonder how such a magnificently beautiful country (the rural landscapes of Japan are among the most stunning we have ever seen) could possibly have been to such an extent degraded by the construction of so many horrendous buildings. Wherever you look, you find dreadful structures of cement and plastic, which in no way fit into the beauty of the surroundings.

Electricity poles are visible everywhere and in large numbers, even in the most pristine landscapes. Large industrial plants occupy some of the most scenic beaches. And, worst of all, the Japanese have a habit of just abandoning buildings they no longer like. So as you travel, you see ruins everywhere, with no authority apparently asking the former owners to tear down or refurbish unused urban structures.

Even fashionable restaurants, which serve exquisite food by beautifully dressed ladies in kimonos, are brightly illuminated with enormous, often ill-placed, neon lights. It’s not uncommon to be eating an extravagant (and expensive) 9-course kaiseki dinner in a room that is lit like a 7-Eleven convenience store.

Where does all of this come from? Some of its has to do with history. The Japanese since the Meiji era (1868 onwards) have embraced “progress”. This means that strong interior lights, plastic and artificial construction materials are embraced, since they are considered “modern” (the more of it you use, the better the result must be, appears to be the logic). At the same time, wood, candlelight (or even light dimmers) are considered “old” and are generally discarded.

But another part is just carelessness. The Japanese, who are so precise and pedantic in ordering you where exactly to place your shoes before you enter a shop, and of sternly reminding you that you must exchange the “indoor” slippers with the “toilet” slippers before you go to a restroom (see section on slippers below), seem not to give a hoot about the large urban horrors they build with the ugliest concrete in the middle of beautiful forests. They also regularly cut down large numbers of beautiful, often centenary, trees in many cities, “so there is more light”. Generally, the Japanese have an aversion to the countryside, which they consider to be “dirty”.

The Japanese disregard for the environment isn’t only visible in urban planning. It’s also present in the lack of organic food (practically non-existent) and the savage extermination of animal species (the Japanese are only people who systematically hunt whales and dolphins, sometimes to extinction).

Japan society today – frighteningly rigid

Japanese society describes itself as “tolerant”. It is true that on the surface, Japan appears to be a place where people can live as they please and say what they want without facing overt hostility. For example, if you move into a neighbourhood as a foreigner (or as a Japanese that “looks” or acts out of the norm) you are unlikely to be confronted with open hostility.

However, this apparent tolerance can be misleading. While people may not confront you directly, their disapproval will manifest itself in subtle ways, such as ignoring you or quietly judging your actions behind your back. This creates a troublesome dynamic where individuals may feel free to express themselves, yet remain unaware of the underlying social currents that shape their interactions.

The role of conformity

In fact, Japanese society is deeply rooted in conformity. From the moment you step into someone’s home and remove your shoes to the generally strictly structured menus at restaurants, which allow for no variations or special requests, there are clear expectations for behaviour (the message is very clear: shut up and accept whatever is presented to you).

These rules provide a sense of order and predictability, simplifying daily life for those who adhere to them.

However, for those who don’t fit into this highly regimented framework, life in Japan can be hell. Some choose to leave the country, hoping for a more open environment abroad. Others retreat into themselves, becoming recluses or finding solace in small and often isolated alternative communities. Many commit suicide (Japan has one of the highest rates of suicide and loneliness of any industrialised nation).

The unspoken and the unresolved

One of the most intriguing aspects of Japanese culture is the tendency to leave things unsaid. In many cases, conflicts or disagreements are not openly addressed but are instead left to linger in the air. This approach can be seen as a reflection of Zen philosophy, which emphasises letting go of the need for resolution and accepting the chaos of reality.

While this can be a valuable lesson in detachment, it also raises questions about the long-term impact on mental well-being. Unresolved tensions can create a sense of unease, even if they are not openly acknowledged.

Friendship in Japanese society

Friendship in Japan is often characterised by a certain level of formality and distance. Unlike in some Western cultures, where friendships may involve deep emotional connections and open communication, Japanese friendships tend to be more reserved. People are careful not to overstay a visit to a friend or “burden” their friends with their “problems”. But of course problems don’t disappear this way, they linger and lead to frustration and escapism into alcohol, sex and other addictions, like pachinko, where Japan is a world leader.

A nation that celebrates interdictions

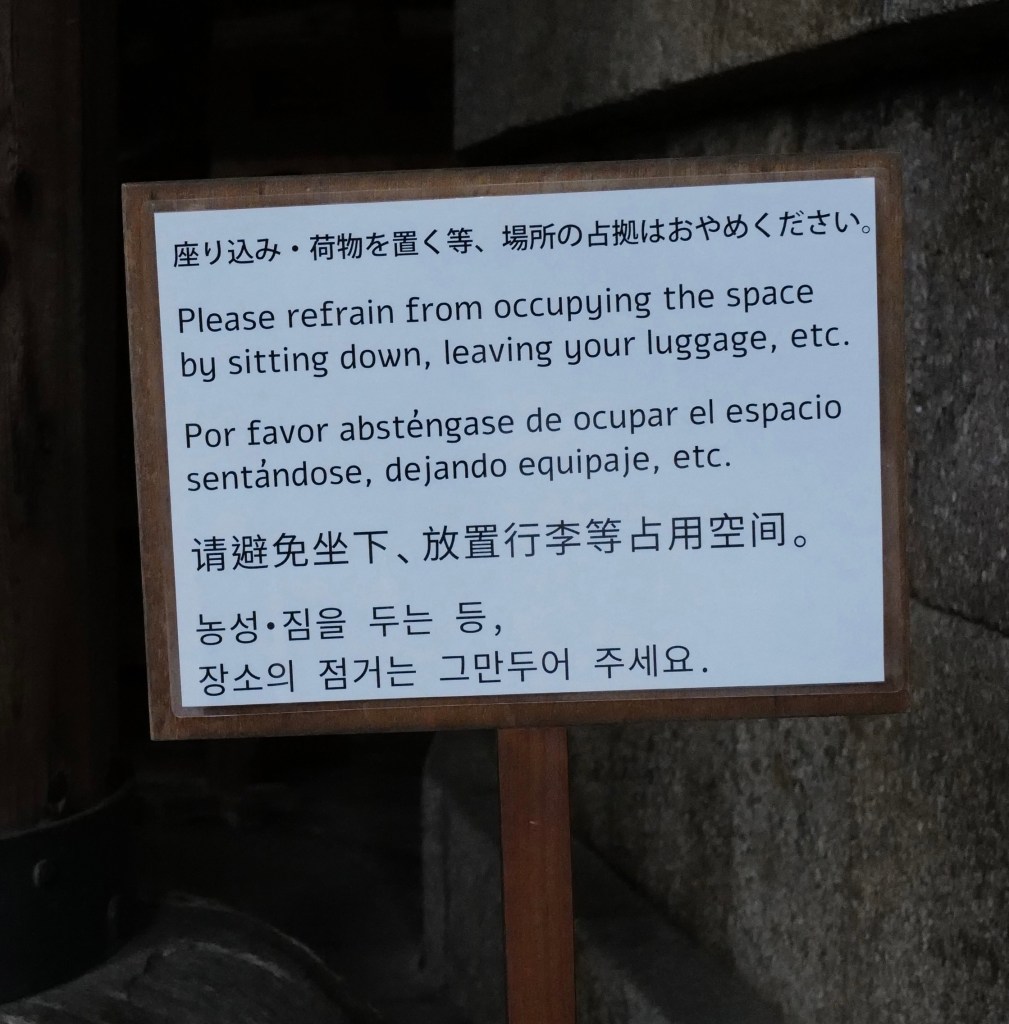

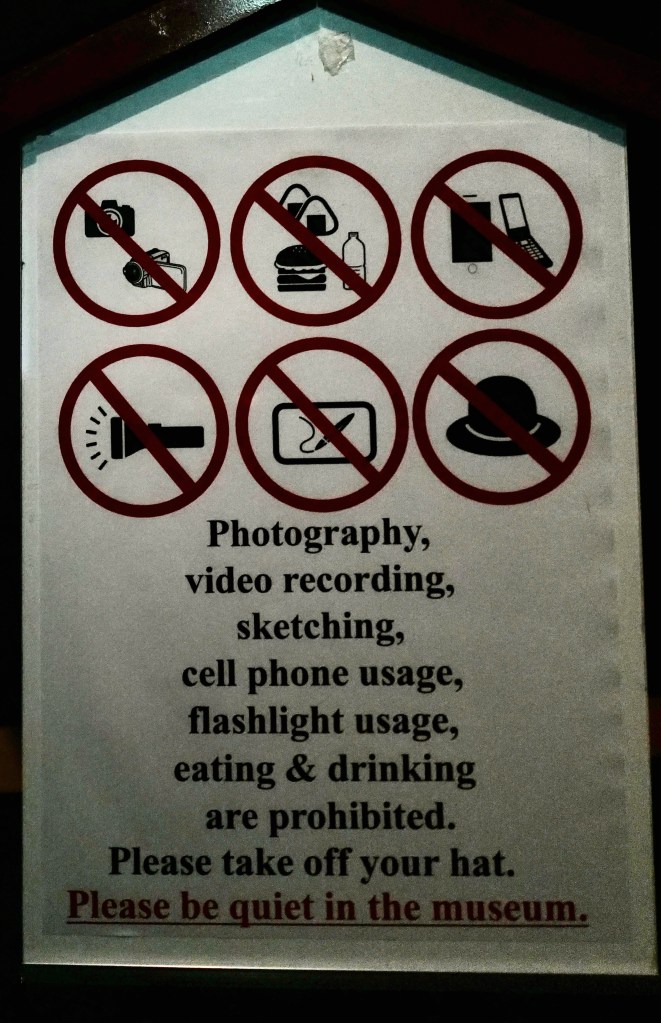

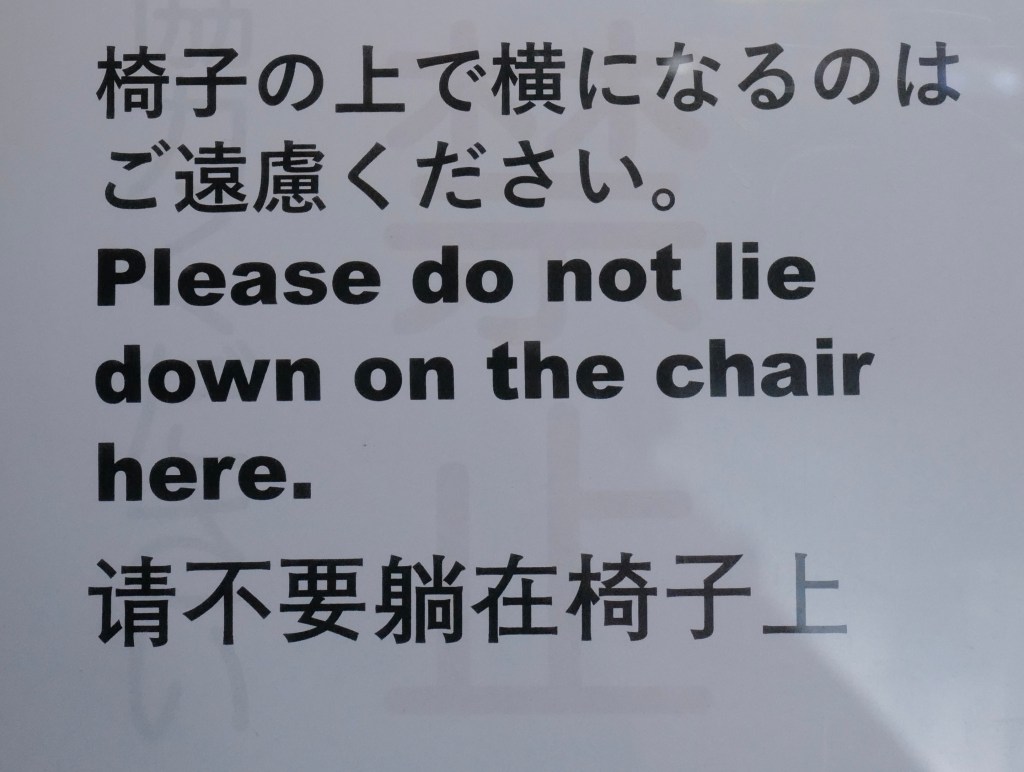

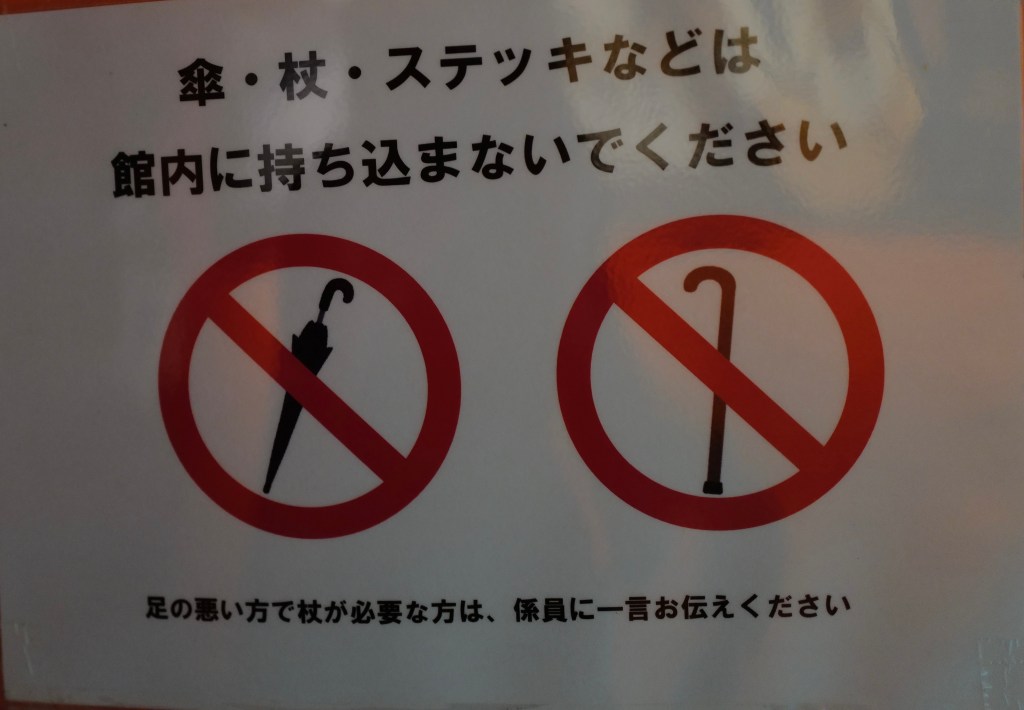

Wherever you go in Japan, you are faced with signs loudly telling you what not to do. Sometimes there are so many signs, that they get in the way of you actually seeing anything. We collected images from over 200 signposts we came across and put them in a file we labelled “Don’t”. Below we show you only the most salient examples.

The Japanese obsession with taking off shoes

At the most basic level, taking off your shoes inside a Japanese home (and most temples, as well as some shops and most traditional hotels) is about cleanliness. Shoes that have been worn outside are considered dirty. But in Japan this has led to a mania, fuelled by the deeply held notion that dirt and disorder are “spiritually impure”.

In many places it’s not just about removing your shoes before entering somewhere, it’s also about which slippers you should be wearing once inside. Often there are three pairs available, depending on the surface you are stepping on, plus a fourth (no slippers, but no barefoot feet either, you need socks for these surfaces). You better not get it wrong otherwise you will easily be shouted at. Here is a rundown:

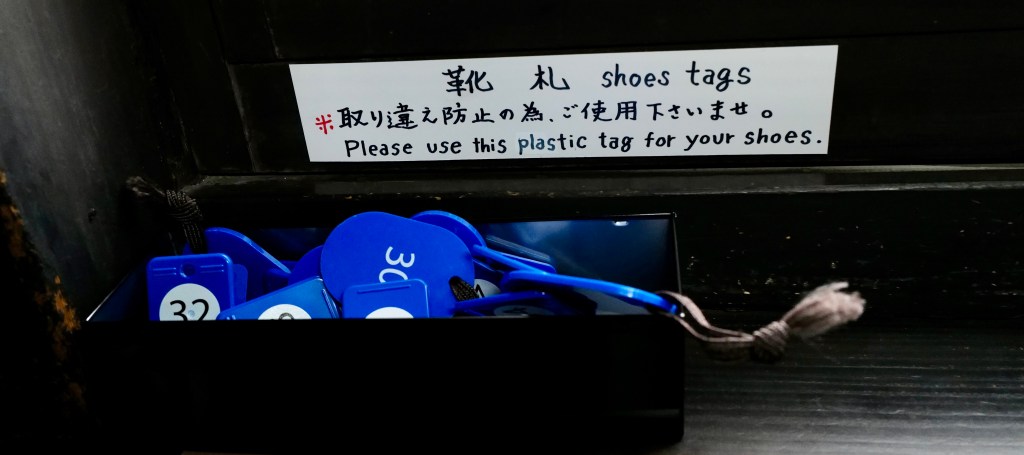

As you enter: Remove your outdoor shoes in a specially designed area called genkan and put on standard slippers. Make sure you tag your shoes before leaving them in a specially designed area (without a tag, someone else might take them!).

Toilet slippers: Bathrooms are seen as “unclean,” so there’s often a pair of toilet-only slippers you switch into when entering the bathroom. It’s a whole sub-zone.

Outdoor slippers: Some homes, shops, hotels or temples have outdoor areas, requiring a third type of slipper.

Tatamis: Areas covered with tatamis are “no slipper” areas, but for heaven sake don’t walk on them barefoot (you might bring in microbes!). So for these areas you are required to wear socks (preferably white).

Privacy is written with a capital P in Japan

Typically, common areas in Japanese hotels feature no sofas and rarely have chairs that face each other. In fact, in most traditional Japanese hotels you will find single chairs facing towards the outside, never the inside.

Hotels don’t design common spaces by chance, they do so in order to satisfy customer needs, so the message could not be clearer: it’s best not to put guests in the embarrassing situation of having to potentially face people they might not know. It should therefore not surprise anyone that we are dealing here with a society which is worried to the extreme about the spontaneous and the unplanned, such as an encounter with people you don’t know in the lobby of a hotel.

A nation of contrasts

Contemporary Japan is a striking study of contrasts. The tranquility of a tea ceremony can be juxtaposed with the cacophony of a pachinko parlor. The natural beauty of a Zen garden exists alongside the artificial perfection of a meticulously pruned bonsai tree. The extreme politeness and big smiles present as you arrive in any restaurant contrasts with a resolute “no”, should you ever dare to ask for an egg on your salad (even if eggs are available in the kitchen).

It should therefore come as no surprise that Japan is at present faced with a critical demographic and economic problem: as in most industrial nations, the population is aging rapidly, but practically no young foreigners are able (or willing) to relocate to this nation, which puts all of its emphasis on appearing externally “nice and polite”, but practically none on the substance of what makes human societies great: sincerity, openness and authenticity.