With a population of just over 100 million, Egypt is one of Africa’s largest countries. It’s also one of the most fascinating places you can visit, the birthplace of one of the world’s oldest civilisations. But this country has a lot more to offer than (amazingly well) preserved vestiges of a glorious past. Modern-day Egypt also allows visitors an excellent glimpse into early christianity, and an introduction into modern-day islam, as well as helping you gain an understanding of the Arab world. This, combined with strikingly beautiful scenery, makes it an irresistible travel destination.

We spent two wonderful weeks in Egypt in May 2021. We used Cairo, Luxor and Aswan as bases, from where we visited a large number of sites. Planes were used between destinations, except for the trip from Luxor to Aswan, which we did by boat. Abercrombie & Kent organised the tour for us and they were brilliant, we can highly recommend them. We are also indebted to Doryane Viala, who kindly commented our itinerary and introduced excellent additions.

Below are our insights and reflections on what we heard and saw in this uniquely fascinating country. At the end, you will also find a hotel review.

As has often been the case in the history of humanity, it was climate change that had the biggest impact on the development of what is now Egypt. And it’s also climate that has been responsible for the fact that so many of Egypt’s ancient treasures have remained so well preserved.

Until about 10’000 years ago, northern Africa was not a desert, but a very fertile part of the world. Vast, lush savannah covered what is now the Sahara, and abundant rainfall meant that large groups of animals roamed the area, offering plenty of food to the groups of hunter-gatherers present in this region. Rapid climatic change, however, transformed the area into what Egypt is today: a desert traversed by only one river, the Nile. Average annual rainfall in Egypt, apart from a small area bordering the Mediterranean, is close to zero.

The rapid disappearance of readily available sources of food meant that the inhabitants of ancient Egypt had to settle permanently in the only area offering sustenance: the Nile. And in order to survive on this narrow strip of land, they had to focus on agriculture.

This transformation, from a nomadic hunting/gathering lifestyle to an agricultural society, the ancient Egyptians achieved rapidly and with great success, to the point where at around 5000 BC, they were producing food far in excess of their immediate needs. The surplus of food, in turn, allowed them to develop an incredibly sophisticated society. Art, architecture, story-telling and religion flourished to an extent that has rarely, if ever, been repeated in human history.

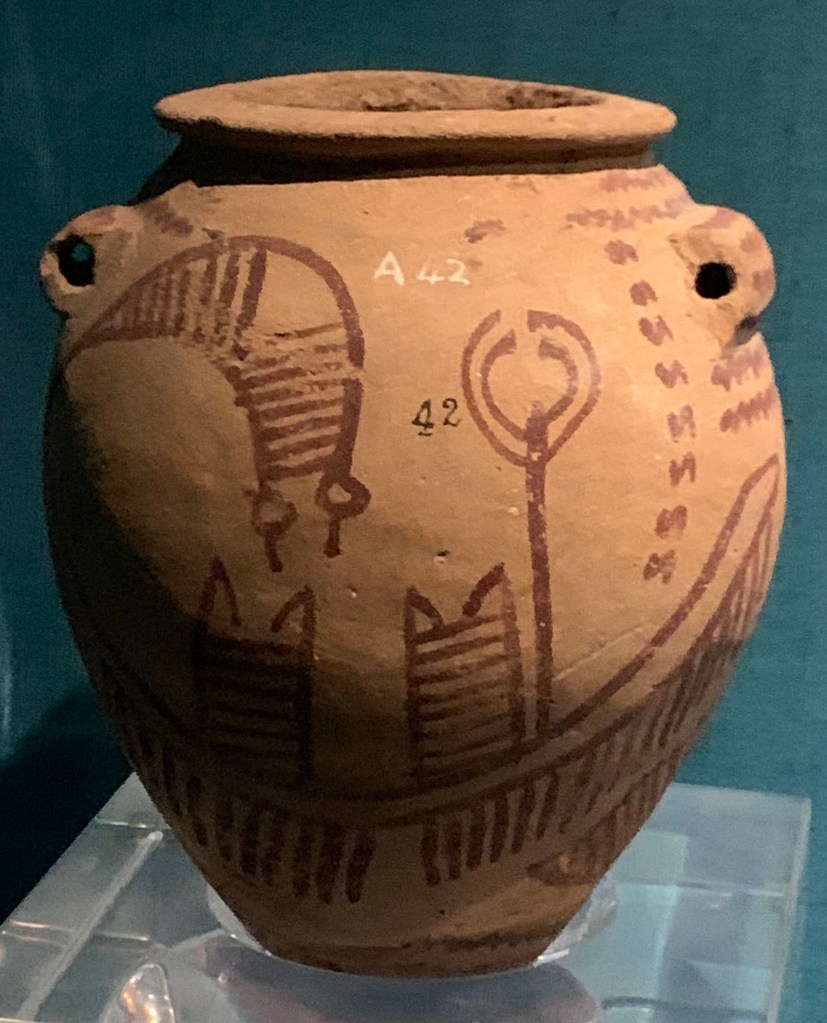

By 4000 BC, at a time when in Europe agriculture was still in its infancy and most humans were hunter/gatherers, Egyptians were solidly established in villages and manufacturing a vast array of sophisticated utensils, including beautifully decorated pots like these:

By 4000 BC, the Egyptians were producing splendidly carved stoneware for their daily use, which looks incredibly contemporary:

The pot shown below, which is almost 6 thousand years old, shows illustrations of ostriches at the bottom. These animals did not exist in Egypt at the time. This indicates that, already at this early time, Egyptians were travelling throughout Africa:

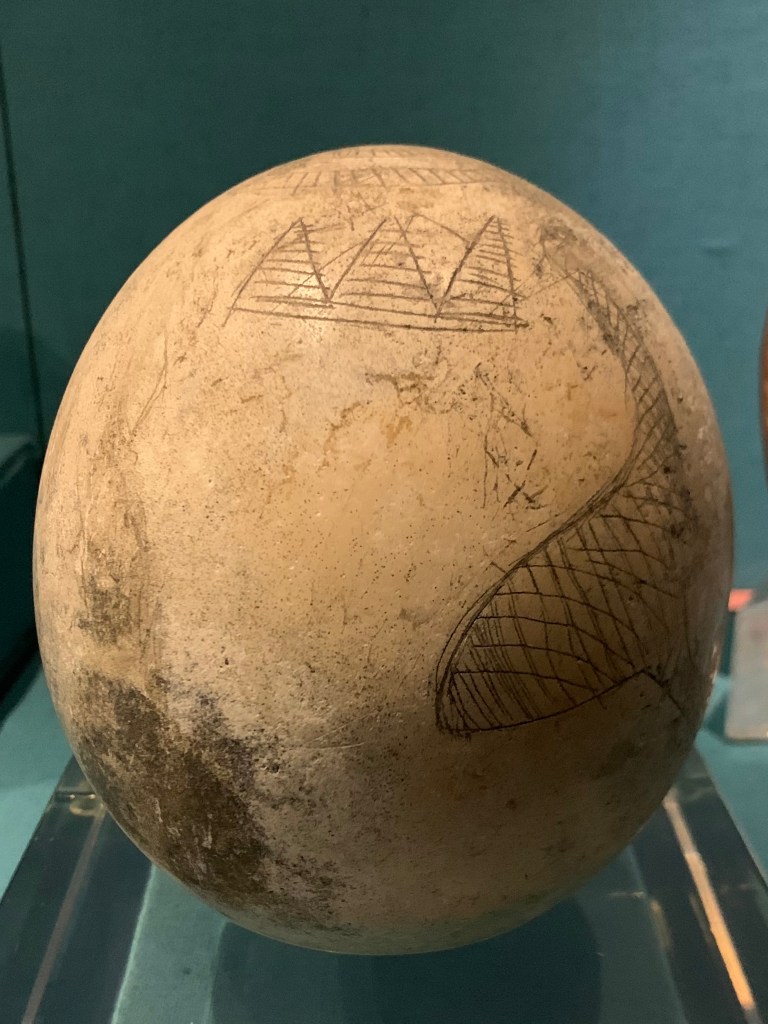

The Egpyptian fascination with ostriches led them to also delicately carve some of their eggs, as seen below (object dating from approx. 4000 BC):

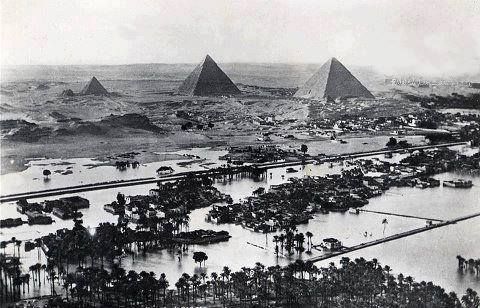

From about 7000 BC onwards, the weather in Egypt became totally predictable, with the Nile producing yearly floods between June and September, which filled the river’s flat valley with not only water, but also a rich topsoil, allowing for generous crops and wildlife to prosper.

The four months of the year when the land was flooded and agricultural work was not possible, offered the Egpytian kings the workforce needed to engage in massive construction projects, including of course the pyramids.

Contrary to popular myth, it wasn’t slaves who were responsible for the extraordinary constructions achieved by the ancient Egyptians, but the country’s peasantry, who by the 2nd millennium BC were more than 3 million. This very large group afforded Egypt’s leadership a readily available and motivated workforce, every year for a third of the year. The peasants, as the rest of the ancient Egyptian society, were energised by a strong belief that the well-being of their kings in the afterlife guaranteed the stability and long-term prosperity of Egypt, so they participated in the gargantuan construction projects of the rulers’ tombs with great dedication. They were, however, amply compensated with food, clothing and shelter during the time that they worked on the constructions (ancient Egypt did not have a monetary system).

By 2600 BC, a first massive construction was achieved, the step pyramid of Saqqara, the burial site for King Djoser. Several million limestones blocks, each one weighing about 2.5 tons, were carved out of quarries, transported over sometimes long distances and dragged to the building site, where they were hauled by hand to the top of what became a 60m-high building of almost 300’000 cubic metres.

Less than 50 years later, in about 2550 BC, King Snefru would build an even more impressive structure, the first pyramid with a smooth white and glitering limestone covering, which captured and refracted the light of the sun. How majestic the view must have been from a distance! It’s called the “bent” pyramid because halfway up, the engineers seem to have altered the angle, making it less steep. Whether this was due to signs of instability in the construction or the need to finish faster, is unclear. Nevertheless, it’s an amazing building, which paved the way for the construction of Egypt’s great three pyramids in Gizeh in the following years.

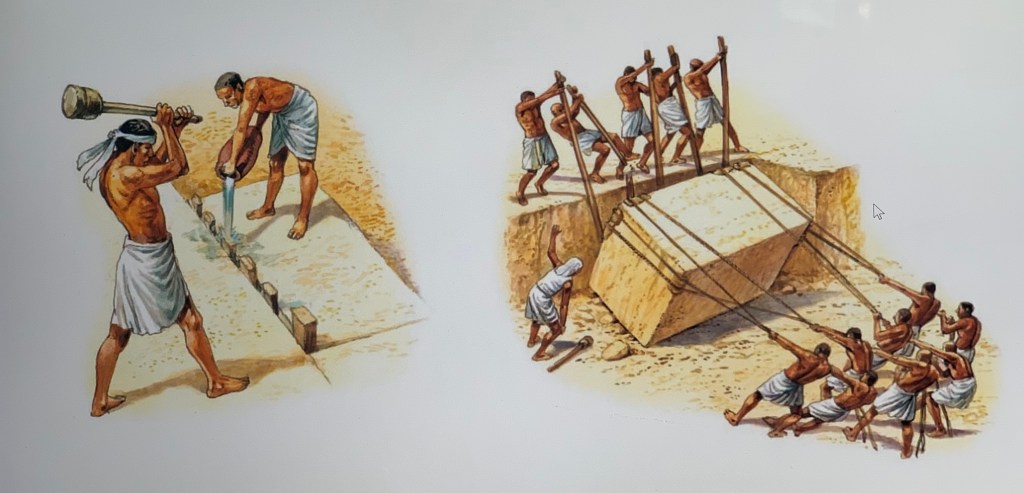

The large blocks used for the construction of the Saqqara, the “bent” and the great pyramids were primarily made of limestone and cut out of the rock by inserting wooden beams into holes, which were subsequently humified with water. When the wood expanded, it broke the stone, which was then hauled with ropes and dragged on ramps to the site of the pyramid.

At the construction site, the stones were also hauled up to the top of the pyramids by using large ramps constructed of stone rubble.

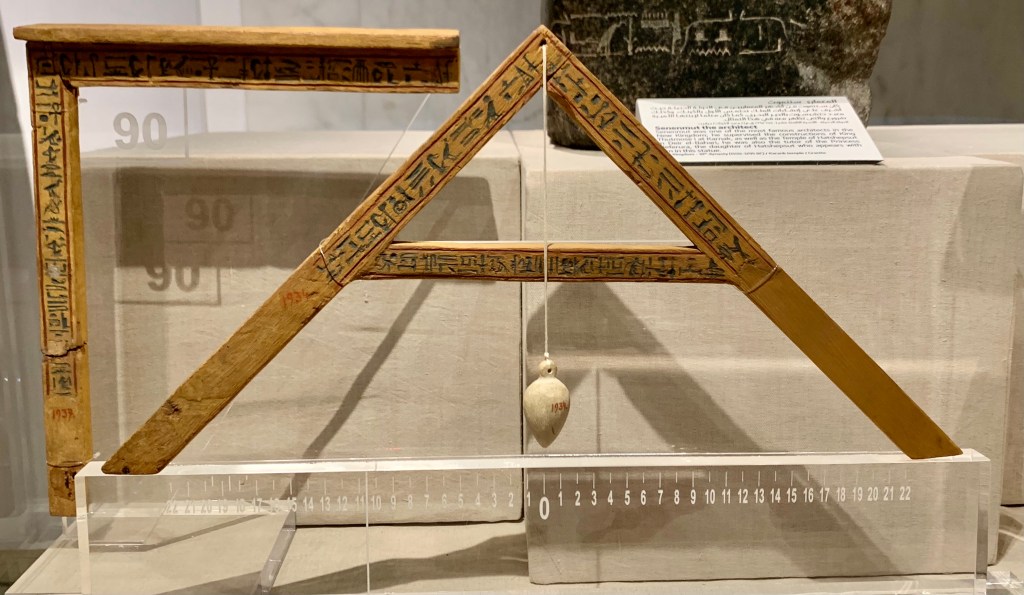

The ancient Egyptians used sophisticated measuring instruments, made out of wood. They could easily still be used today!

Once the construction was finished, the “bent” and great pyramids were covered in fine limestone, giving them a very beautiful polished look and a brilliance in the sun that could be seen from hundreds of kilometers away. Some of this fine limestone covering is still visible at the top of the pyramid of King Khafre (centre of photo):

The top of King Khufu’s pyramid, dating from 2500 BC, now exhibited at the bottom of the pyramid, shows the extraordinarily fine workmanship (with perfect joints) of the time:

Inside Khufu’s pyramid, in his burial chamber, there are several large granite blocks, which fit into each other with extraordinary precision. How this was possible without the use of mortar and what kind of tools were used, is still an unsolved mystery.

Pointing to a road construction made about 5 years earlier, now already in tatters, our guide ironised about how much better the workers in Egypt were 4500 years ago!

Limestone was already very difficult to cut and transport, but how did the ancient Egyptians quarry granite, which came from Aswan, which is about 700 km from the great pyramids? This remains a mystery.

We visited an ancient granite quarry while in Aswan, where an uncut obelisk is still visible. It’s probable that stone tools made out of diorite, which is stronger than granite, were used for carving the granit, but what utensils were used to cut and work the granite with, is still unknown.

In our days we would use the most resilient of all stones, the diamond, but these precious stones were not available for construction in ancient Egypt. When we tried to use diorite stones ourselves, we merely advanced by 1 mm after 5 minutes of frantic hitting the granite.

Evidence that the ancient Egyptians must have used machinery or tools beyond the diorite stones we were shown, is provided by the large, very regular carvings on each side of the unfinished pyramid above (which we are using as steps) and also by carvings on the columns of temples like Philae, where the marks seem to indicate that a machine is being sharpened or calibrated. But no such machinery has, as yet, been found. The extraction of such large stones is probably ancient Egypt’s greatest unsolved riddle.

The transport of stones is, however, no mystery: they were ferried down the Nile in wooden barges and, as mentioned, subsequently mounted on-site by pulling them up ramps made of sand or rubble.

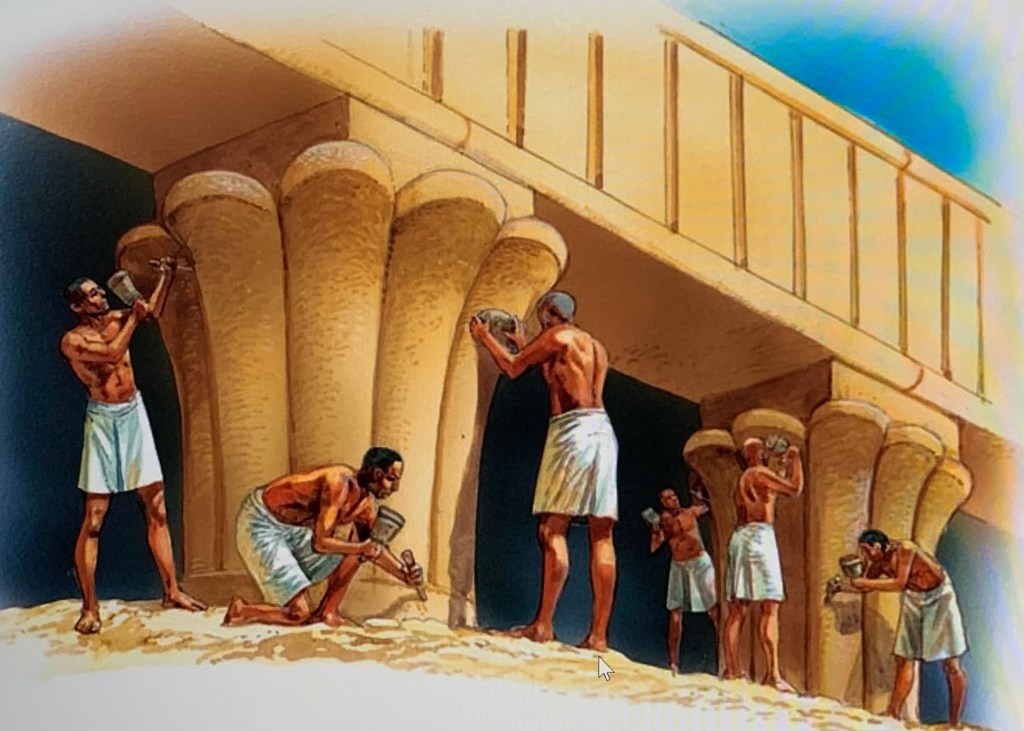

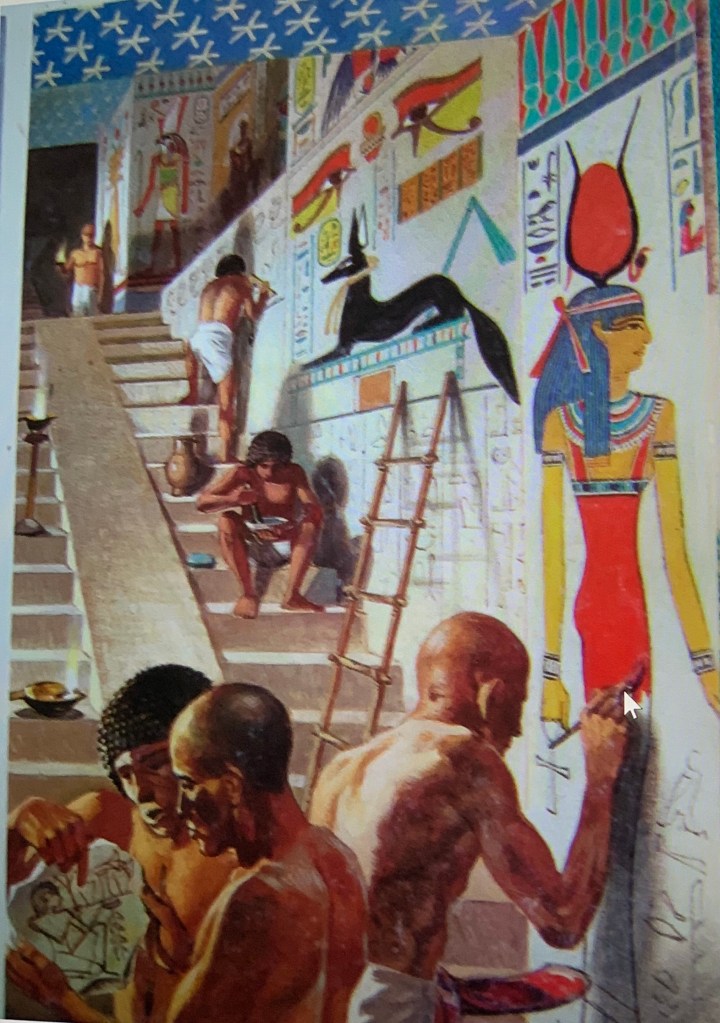

Once the top of the temple was reached, the stonemasons, carvers and painters started working from the top down, until they reached the bottom and all the supporting sand and rubble was removed.

The same procedure was used for the creation of statues – blocks of sometimes monumental size were sent to the temple site, where they were carved out of the rock and then lifted into position.

Construction of pyramids as royal burial sites gradually dwindled after about 2500 BC and from about 1500 BC onwards, Egypt’s rulers preferred to be buried below the ground. They had reached the conclusion that pyramids were far too visible and too easy an invitation to looters, who had already in antiquity desecrated the tombs of their predecessors. In fact, the only object left of Cheops (Khufu), in whose honour the greatest of all pyramids was built, is a 7 cm statue, which requires a magnifying glass to be examined:

From 1500 BC onwards, and for almost 2000 years thereafter, the Egyptians built extraordinarily beautiful underground burial sites, as well as majestic temples across their land.

The most impressive of theses burial sites are found in what is now called the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, but other burial sites for nobles and other important figures in ancient Egypt are visible in many parts of the country.

The Valley of the Kings (and very close to it, the Valley of the Queens) is located a short distance from modern day Luxor (Thebes) in a remote area, which hardly ever receives any rain and where there is little wind.

The Egyptians would start construction of the tomb as soon as a ruler (or anyone else of rank) was crowned or appointed, and work would continue until the person’s death, since it was considered a bad omen to finish work while the individual was still alive – it might have indicated that the person would die soon. This means that in every tomb there is, somewhere, unfinished work.

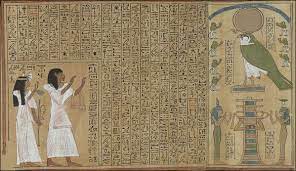

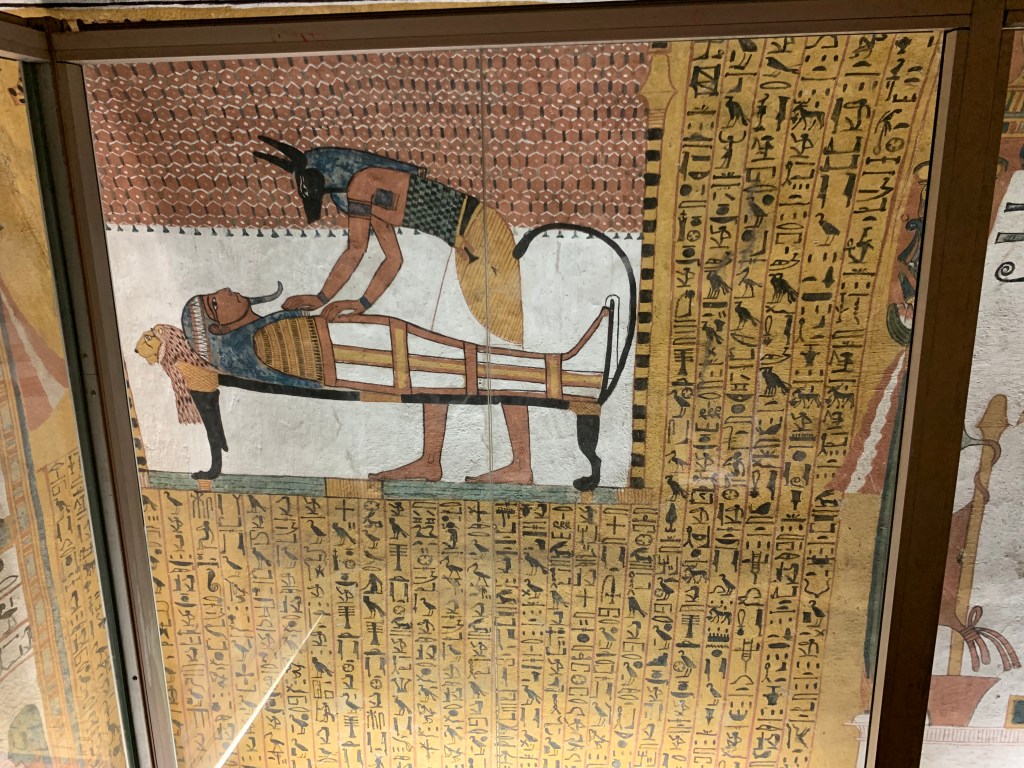

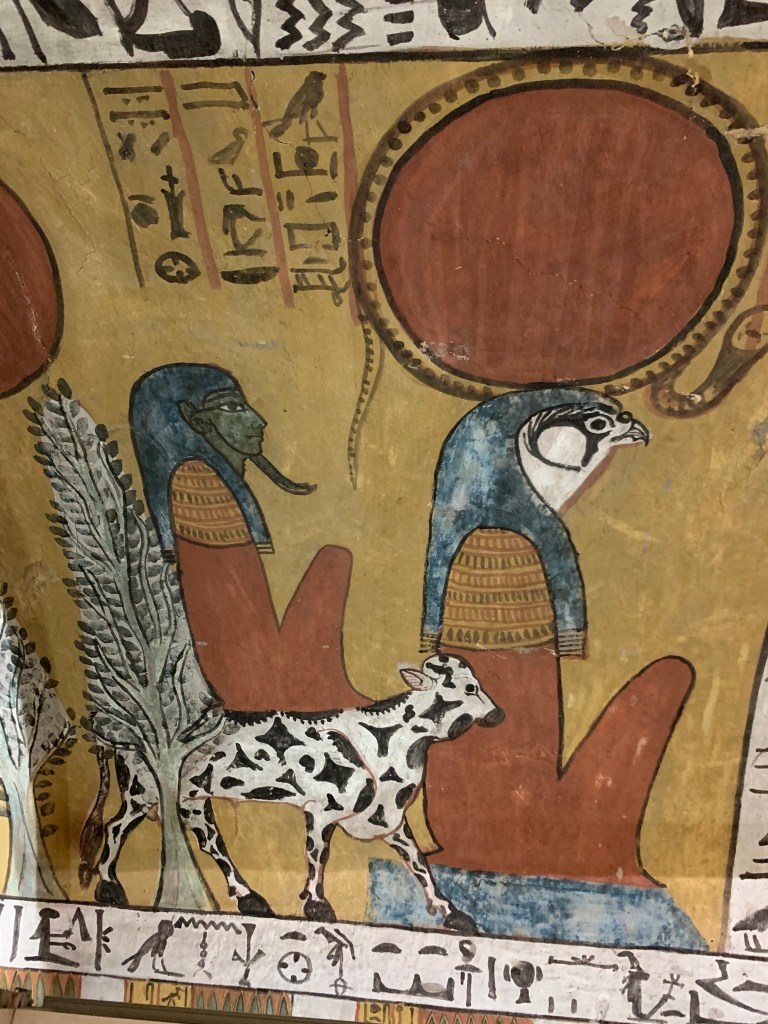

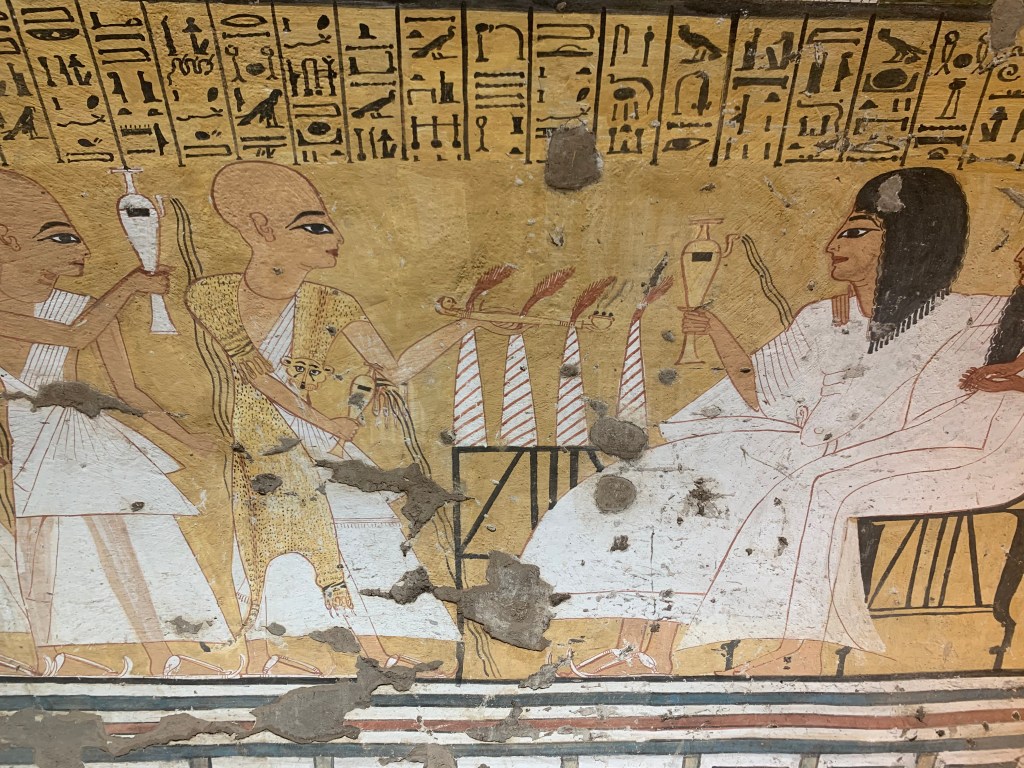

The burial chambers were covered in scenes that would help the deceased, after resurrection, to find his or her way in the netherworld. Many inscriptions contain incantantions and magic spells. Some of these were carved in stone, many were placed on the burial coffin itself and still others were relegated to papyruses. The deceased were depicted in an idealised form, perfectly proportioned, mighty, young and full of vigour.

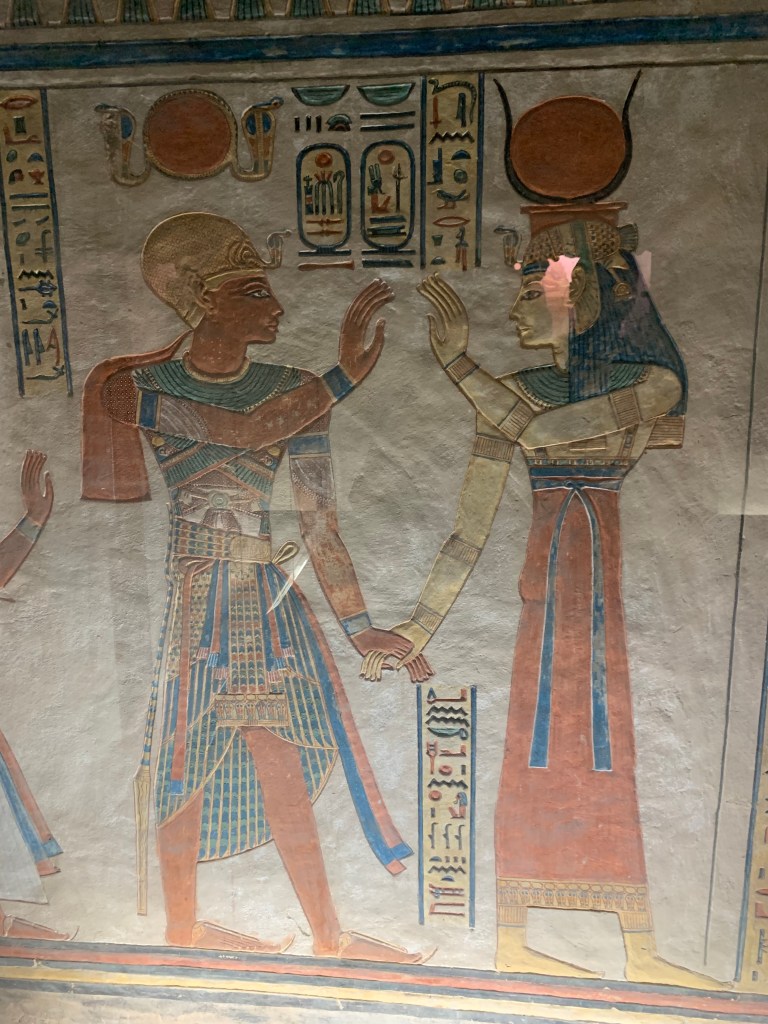

But the tombs also included everyday scenes, for the deceased to remember his life and accomplishments before death. Other scenes helped the deceased with introductions to important gods, who would be of help during the journey in the underworld. The beauty of some of these tombs, most of them completed more than 3500 years ago, is just astonishing. The splendid, almost unaltered colours, the delicate carvings, the detailed incorporation of astrology, are awe-inspiring. One can only remain humble with admiration in front of such beauty.

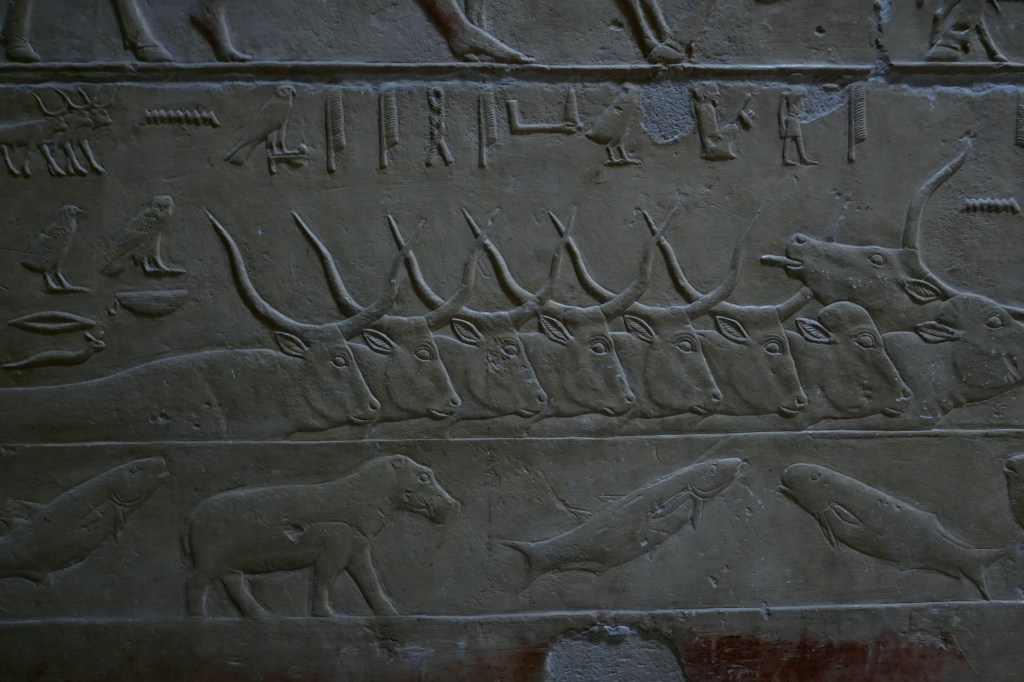

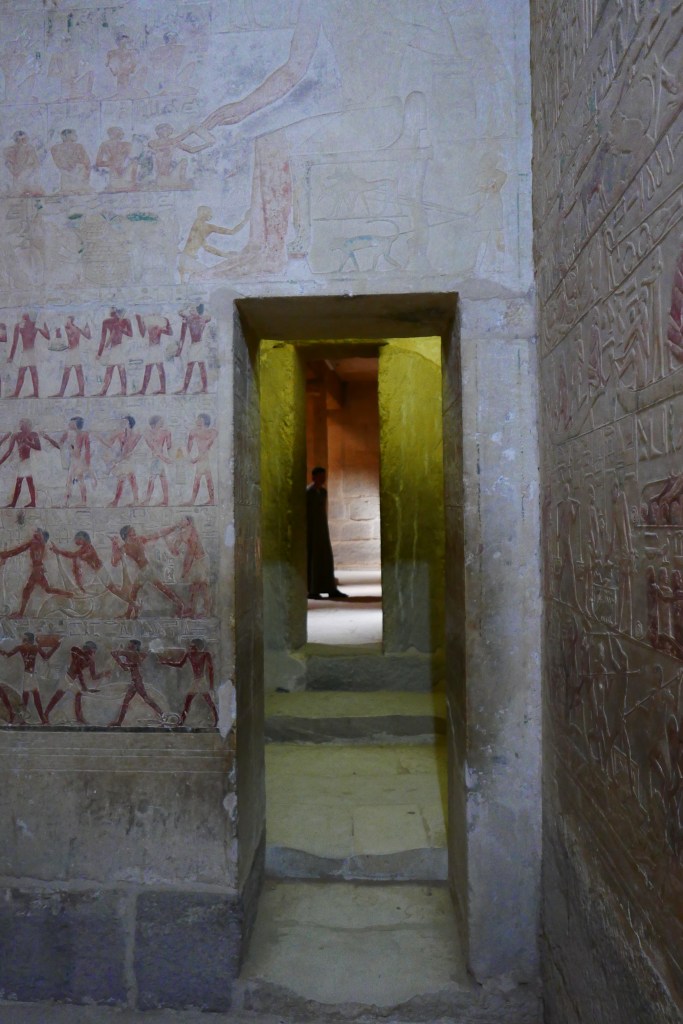

Although most of the scenes in tombs are related to religious rituals, there are still sufficient images that allowed us to see what everyday life was like in ancient Egypt. The images below are from the tomb of Kagemni, a high officer during the reign of King Teti approx. 2300 BC. They show the kinds of animals that roamed Egypt at the time: hippos, crocodiles, jackals, antelopes, gazelles, water buffalos, lions, as well as a large variety of birds and fish. They also indicate that young boys, as well as males from lower social strata, were, at the time, wandering about without covering their genitals.

The ancient Egyptians saw death not as a cut-off point, but as part of a cycle. They observed the sun, how it rose each morning, went down at night and reappeared in the morning. So they thought that after our death, we would spend time, just like the sun did, in the netherworld (a region where the God Osiris reigned) and then, after we were resurrected, we would be reborn and live the same life as before, until we died again, and so on. The idea of this cycle of life and death was entirely based on the observation of the sun and its movement.

The idea that the resurrected would live somewhere else (in heaven or hell, as in the christian or muslim tradition) did not occur to the ancient Egyptians. They thought that the very best place to be resurrected was the Egypt they knew and loved. Egypt was their idea of paradise. This says a lot about how rich the land was and how content most people were with their livelihoods.

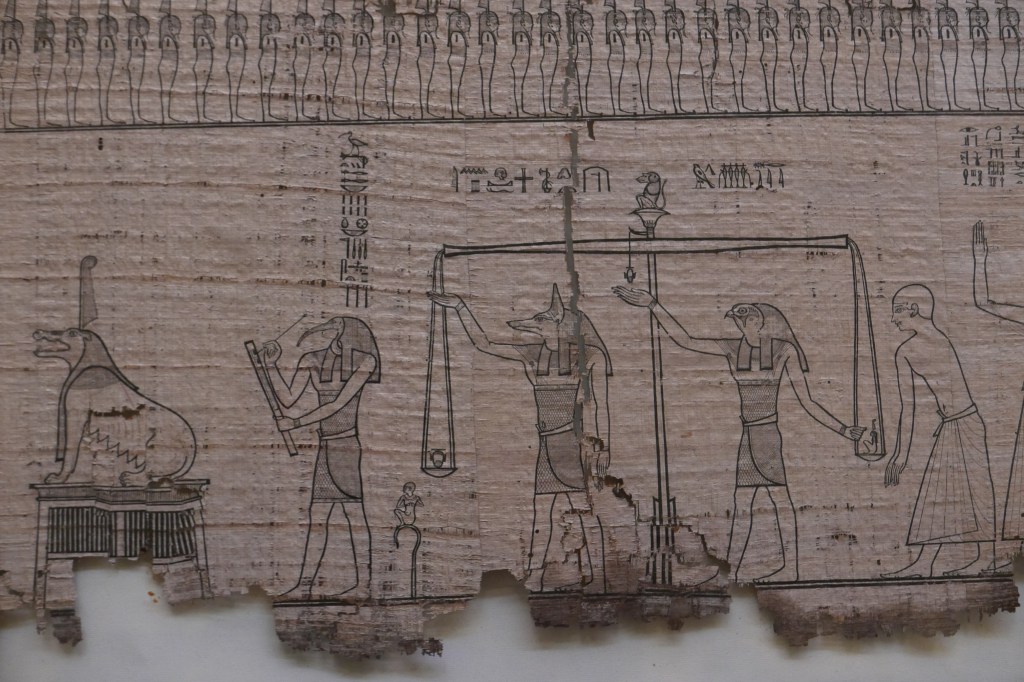

Not everyone was resurrected, however. Immediately after death, a person had to answer 42 questions (Have you stolen?, Have you been jealous?, Have you been clean in body and mind, Have you repayed all debts promptly?, etc.). Only those who had answered all questions satisfactorily had their hearts weighed. And only those whose hearts weighed less than the feather of truth, were worthy of continuing into the afterlife. In slightly adapted form, the concept of a final judgement was taken over by christianity and islam.

Other ancient Egyptian stories that inspired the early christians, was the virgin birth of the god Horus. According to this myth, the goddess Isis conceived a son (Horus) with her husband and brother, the god Osiris. This happend hrough magical spells, since Osiris had been dismembered and his male organs were never recovered. The virgin birth of Jesus is strongly reminiscent of this story.

Mumification was intended to preserve the body, so the soul would recognise and return to “its” body. False doors were designed in the burial chambers so that the soul, after wandering for a while, would be able to come back and inhabit the mummified body.

The ancient Egyptians developed very sophisticated techniques for the preservation of the body after death, removing the internal organs and placing them in special canopy vases, so that they could be reunited with the deceased after resurrection. The bodies were often so well preserved that seeing them now creates an eery sense of presence.

Not only humans, but animals were often mumified. Below are examples of crocodiles and rams who, after being associated with god-like virtues, were also mumified.

Early Christians used the expertise of the Egyptians to mumify their bodies and coptic images show Jesus being brought down from the cross in mumified form.

The most impressive scenes in tombs were carved into the rock, but this was only reserved for kings, very high-ranking officers and priests.

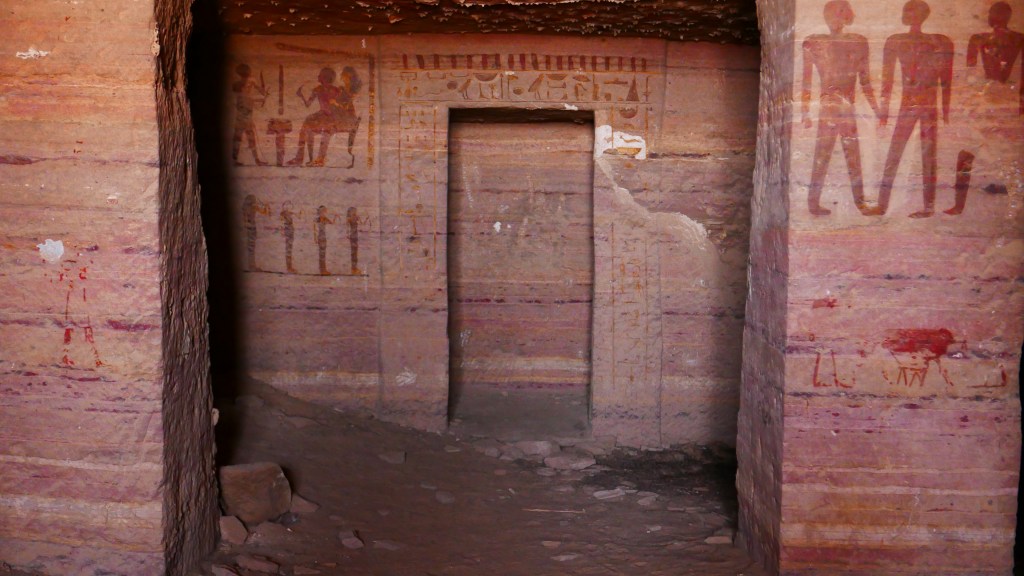

Lesser officials usually did not have access to carved images in their tombs, which would have been too expensive for them. Their tombs were nevertheless extaordinarily beautiful.

Lower-ranked nobles had fewer images and their tombs were much simpler, but nevertheless impressive.

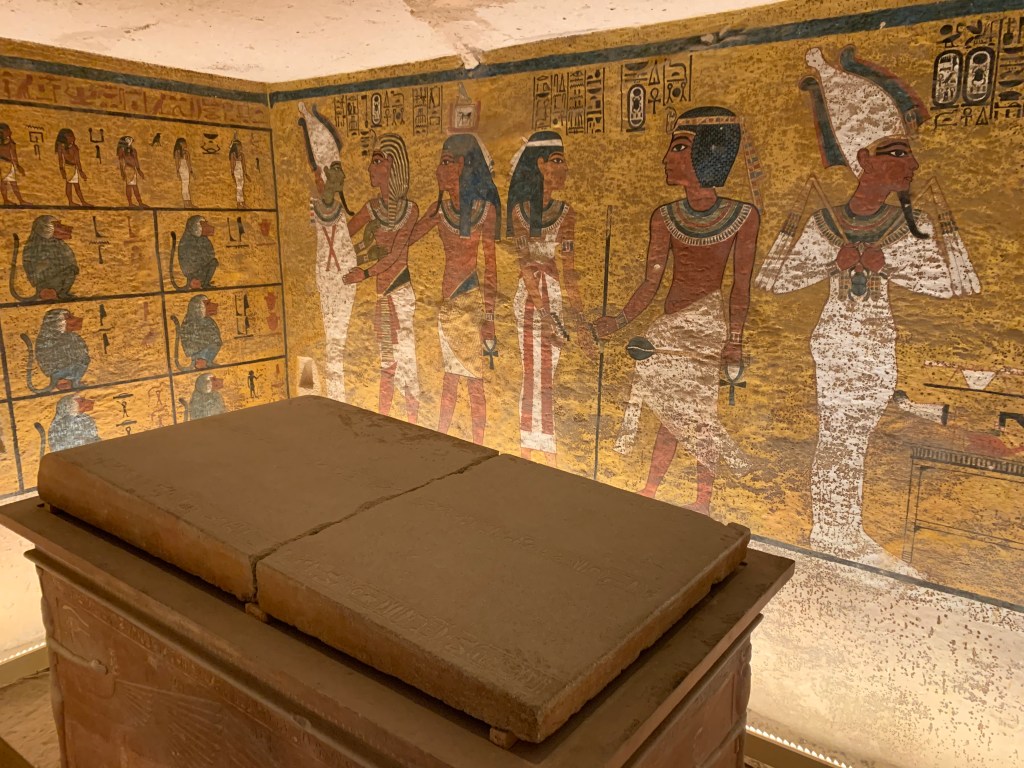

In the case of some kings, who reigned for a short time and who died suddenly, the tombs were painted, not carved since time did not allow for the more time-consuming carving process. Such was the case of Tutankamon’s tomb (1342 BC), a relatively modest burial site in the Valley of the Kings. Tutankamon died unexpectedly when he was 18. Therefore, due to the lack of time, not all the walls are covered in this tomb and there are no carvings. There is no comparison with the magnificence of King Seti I’s burial chambers.

Tombs were of course private spheres, where no one was supposed to enter, so the pictorial focus was on one-to-one dialogues with the deceased, on helping him find his way in the next life.

The temples, however, were visited by thousands of people, so they often served as propaganda forums for the kings, eager to show their power and status.

Ramses II (approx. 1300 BC), ancient Egypt’s longest ruler (67 years) used the many temples constructed during his reign to develop a personality cult which would have made Mao, Stalin or (Kim Il-Sung) incredibly envious.

Every temple you go to (and there are many) built in Ramses II’s time is filled first and foremost with monumental figures showing the king. The gods to which the temples are dedicated, appear in much smaller format.

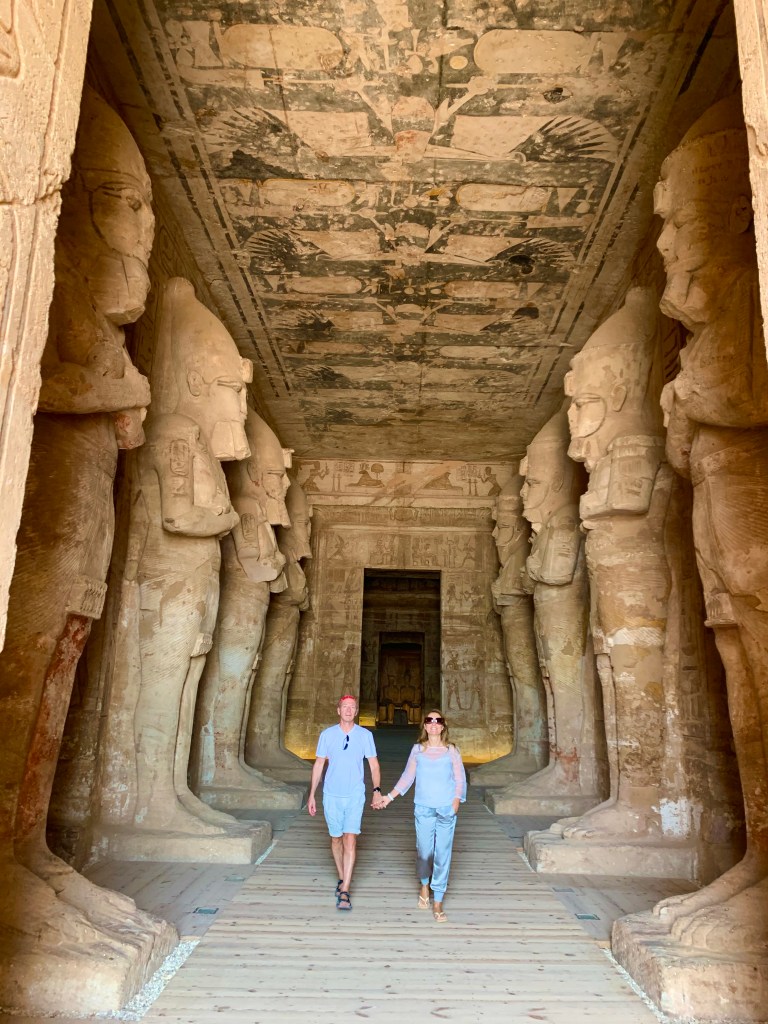

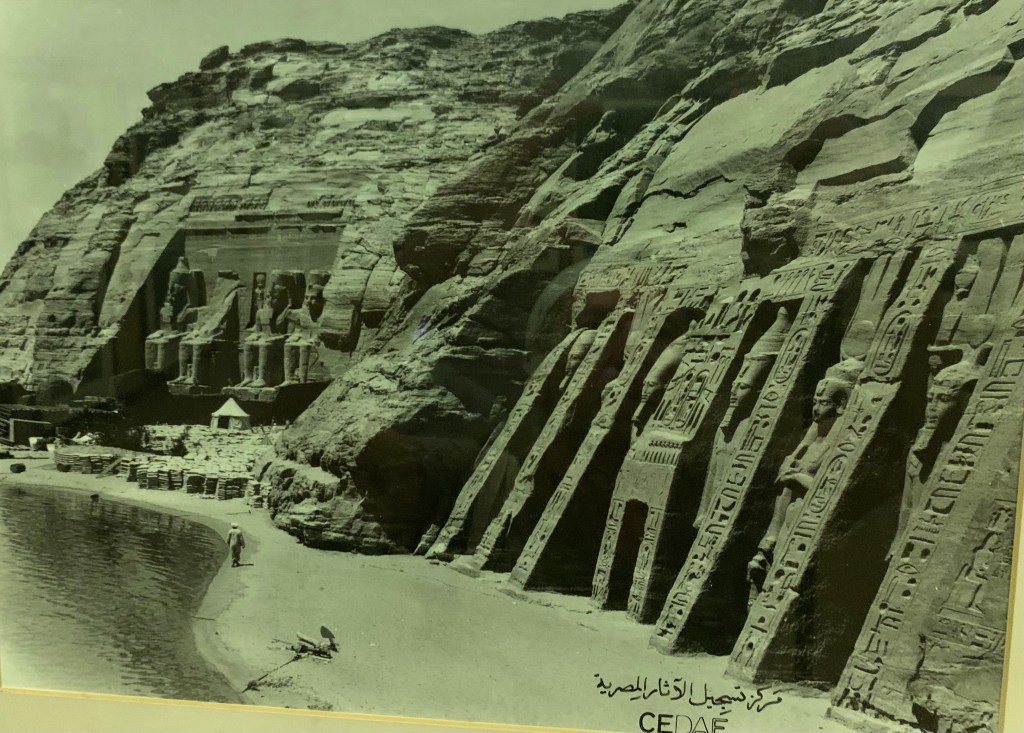

This can be seen clearest at Abu Simbel, Ramses II’s amazing temple dedicated to Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah…and to the deified Ramses himself. At the entrance, there are four colossal statues of the seated king, each 21 m high. Only if you look carefully do you see (in much smaller format) the images of the gods.

Inside Abu Simbel, you are greeted by a long colonnade of statues of Ramses II.

The walls are filled with carvings showing the many victorious battles of Ramses II (even though he didn’t have that many, at least not compared to great prior warrior kings, like Tutmosis III).

The king’s passion for himself appears in this battle scene. You see him conducting his chariot while at the same time firing arrows at his opponents (something that would have not been possible, there were always two people in a war chariot, one firing, the other leading the horse).

In the temple of Luxor, initially built by King Amenhotyp III to celebrate Egypt’s Opet Festival, guess who greets you at the entrance? It’s of course Ramses II, with two massive seated statues of himself, plus two additional standing ones (only one still exists).

Inside the temple, large additional space was added during his lifetime, to make room for dozens of additional statues of Ramses II.

Ramses II’s frenzy for himself also led to the destruction of signs indicating the presence of previous rulers. He was especially keen to erase any memory of Queen Hapshepsut, who reigned about 200 years before him. Her magnificent funerary temple is now filled with cartouches of Ramses II, covering and erasing those of the queen, who he considered to have been unfit to reign because she was a woman.

Worried that his own image might be erased by future kings, Ramses II commissioned that the carvings in his temples should be very deeply carved, which would make changes more difficult.

Ramses II wasn’t the only ruler who used temple surfaces to showcase his power, but he remains unsurpassed in his megalomania.

Many of the surfaces of temples show annihilated foreign soldiers with their heads in their hands or on the floor below them. These images were intended ensure that the slain warriors would not be able to resurrect, since in the ancient Egyptian belief system, only complete corpses could do so.

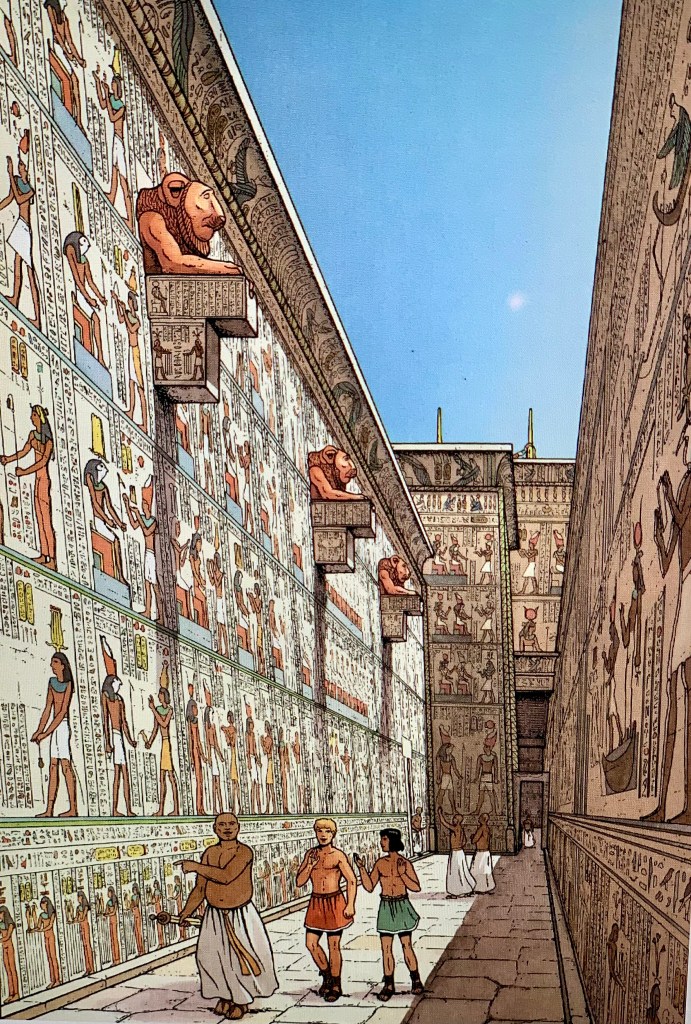

From an architectural standpoint, the ancient Egyptian temples mostly show a consistent pattern: two large entrance walls were followed by a series of rooms (some roofed, others not) of decreasing size, at the very end of which was the smallest room, in which the god’s statue was placed. This area, called the holy of holies, was only accessible to the kings or the highest priests. Most of the people prayed in the largest areas, but the royal family could access the antichamber of the holy of holies.

On one occasion, we had the rare experience of seeing the god’s statue in the holy of holies, the only statue in Egypt that has remained in the same place for over 3300 years. It is the statue of Sekhmet, the goddess of healing at the temple of Karnak, worshipped for millennia for its virtues.

We stood for many minutes, in total silence, feeling what the ancient Egyptians must have felt – a very powerful spiritual presence and a strong communion with the goddess.

To ensure appropriate aeration, especially during Egypt’s hottest months, when temperatures can rise during the day above 50°C, some of the temples were equipped with clever air vents, as shown below in Karnak Temple:

Except for a few remaining colours (mostly visible inside tombs), most of the ancient Egyptian monuments as we see them today, are colourless. However, this wasn’t the case in ancient Egypt. All the public buildings, especially the temples, were painted in bright colours, which must have been dazzling at the time.

Mostly, the artists who worked on the buildings did so anonymously, but occasionally they did sign their work, as in Abu Simbel:

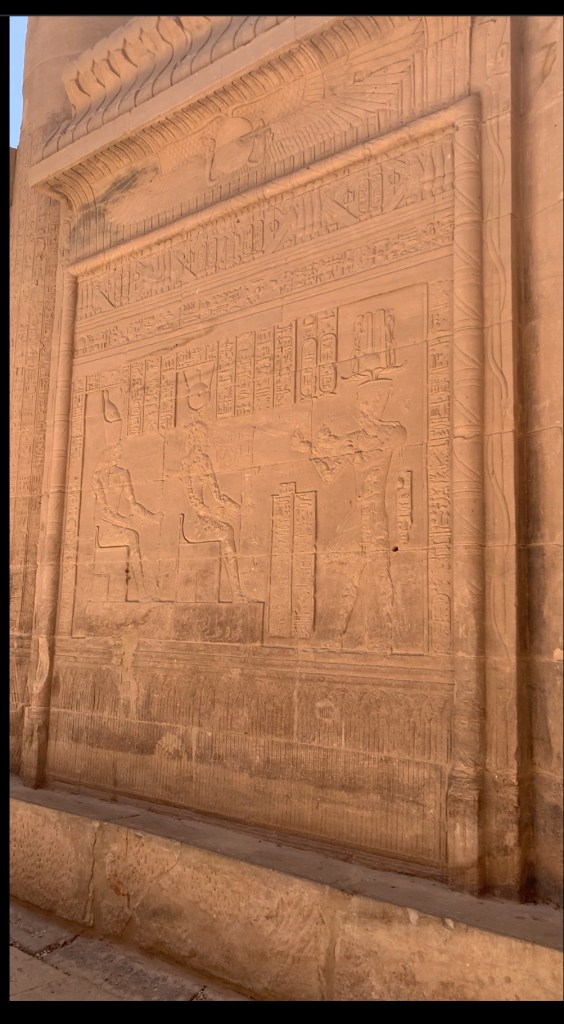

Friezes considered “masterpieces” by the builders, and worthy of special attention, were sometimes framed, as in the example below:

Paintings and sculptures in ancient Egypt were not intended to show reality, they served the sole purpose of illustrating stories and, especially, of making a point to the onlooker. In a world where large parts of the population were unable to read, it was important that the images should impress the people who saw them and be self-explanatory.

There was no intention to show humans the way they really looked, the forms were idealised. From about 3000 BC onwards, for the next three thousand years, the Egyptian iconography follows a similar pictorial pattern and, from a distance, may all seem the same. However, upon closer inspection, significant differences begin to emerge.

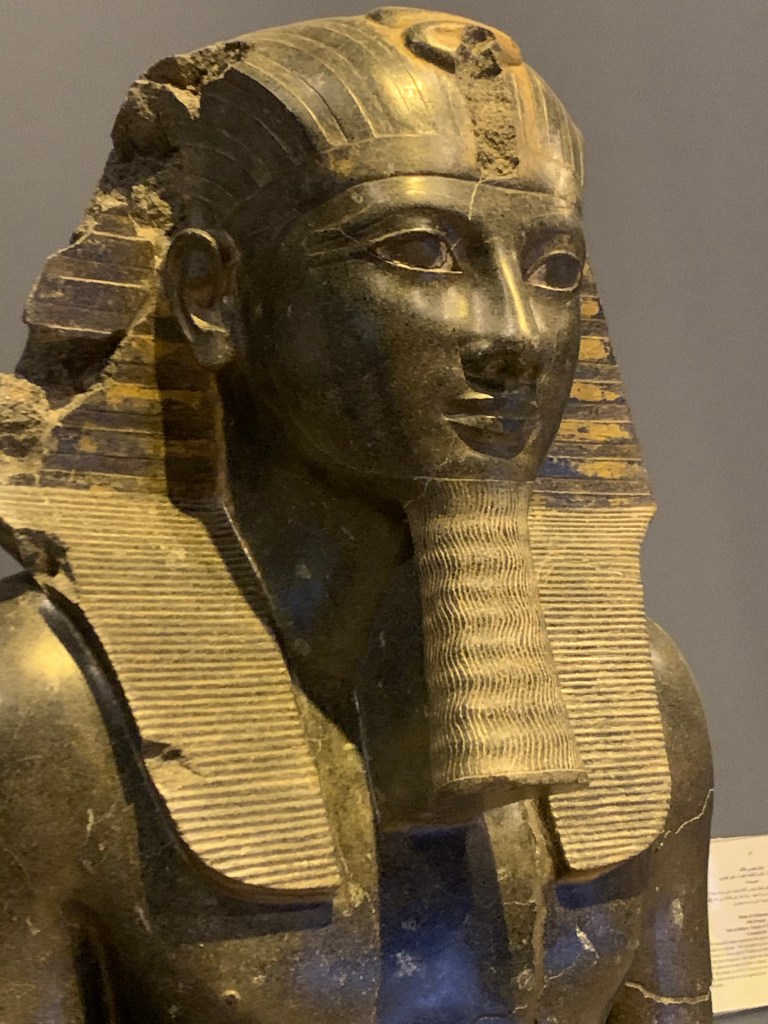

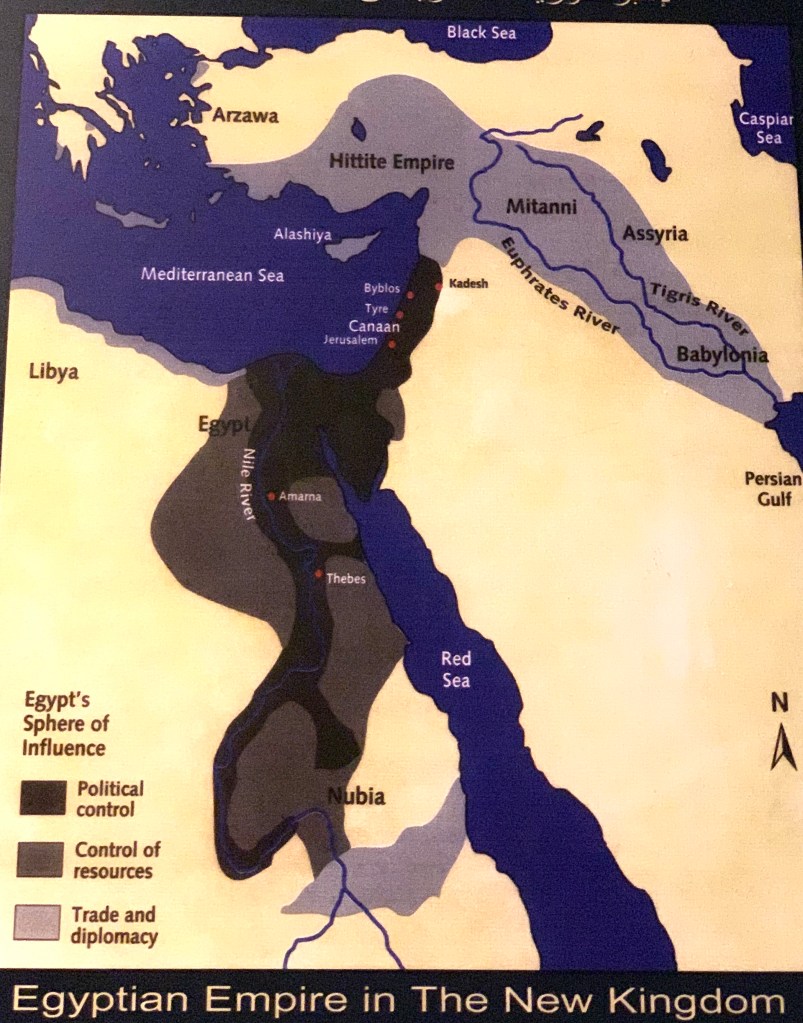

The quiet confidence and youthful looks of the great King Tutmosis III, which appear clearly in the following two sculptures dating from his reign in about 1500 BC, stand in stark contrast to the image of Amenemhat III (about 1800 BC), in which the king appears sad and worried. There was some logic to this: Tutmosis IIIa was probably the greatest warrior in the history of ancient Egypt, successfully expanding the country to the south and north, as shown below. By contrast, Amenemhat III reigned at a time when Egypt was weak, nd plagued by internal fights.

In the long history of ancient Egypt, there was only one brief moment when the iconography changed. This happened around 1350 BC, during the reign of Amunhotyp IV, who radically changed the religion and transformed Egypt into a monotheist state. The king changed his own name to Akhenaton (“benefactor to Aton”) and elevated the sun god to become the only god (Aton). Akhenaton also moved the capital from Thebes to Amarna.

During his brief reign (about 20 years, of which during the first 5, he was still known as Amunhotyp IV), the Egyptians began to represent the royal family’s faces with real, not idealised features.

There can be no question that Akhenaton’s features were real, as these side-by-side images taken of a present-day Egyptian who we ran into in Aswan, confirms.

Akhenaton’s move to monotheism was not only motivated by religious views. It was a way for him to take power away from the clergy, which had considerably gained in strength. By positioning himself as the sole representative of Aton, now the only Egyptian god, Akhenaton de facto sidelined the clergy and consolidated power in himself. King Henry VIII did exactly the same in 1532, when he disbanded the catholic church, introduced protestantism to England and declared himself the head of a new state religion.

In the following image you see how radically the Egyptian iconography was transformed to highlight the king’s new role – even his wife Nefertiti is shown with her husband’s features, to underscore the king’s role as Aton’s sole representative on earth.

King Akhenaton’s face features, as we have seen, probably showed him the way he really looked, but the rest of his body was deliberately deformed, to portray him with both masculine and feminine features. This was done to underscore his universal role as Aton’s only priest.

Akhenaton’s new religion barely survived him. Tutankamun, who at the age of 9 years succeeded him on the throne, initially appears under the new iconography, but soon thereafter, the clergy convinced the young king to return to the previous religious beliefs and by the time of Tutankamun’s death, when he was 18 years old, Egypt was already back to what it had always been, a politheistic society.

Nevertheless, the power struggles between kings and the clergy were far from over. During the time of Ramses II, it was clear that the king had the supremacy, as is obvious from statues like the one below, where the god (in this case, Horus) is shown much smaller than the ruler, and engaged in a supportive role:

Compare the above to the two sculptures below, where the roles are inversed, with the god taking the predominant role:

In carvings and paintings on walls, when humans were represented, it was usually from their profile. This, according to the ancient Egyptians, allowed for more details to be shown. But there were exceptions. Dwarfs, who held a special rank because they entertained the royal family, and were also in high demand as jewelers because of their small hands, were usually shown from the front, to make the point that they were “different”. Many dwarfs became very wealthy in ancient Egypt, which allowed the males to marry normal-size Egyptians.

There was even a dwarf god in ancient Egypt, called Bes. He was both the god of war and the patron of childbirth, and was also associated with sexuality, humour, dancing and music.

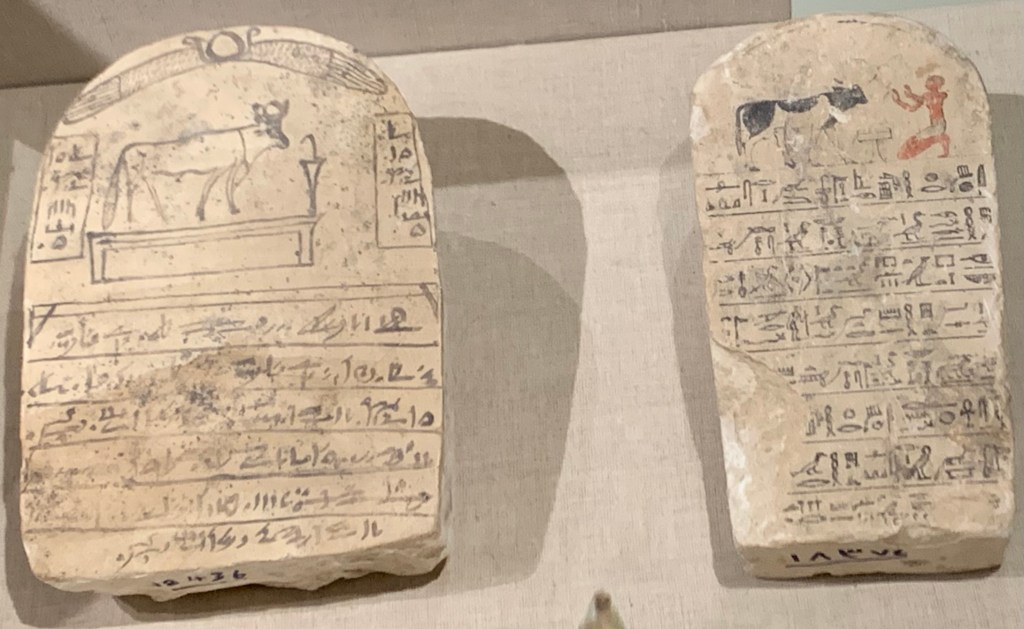

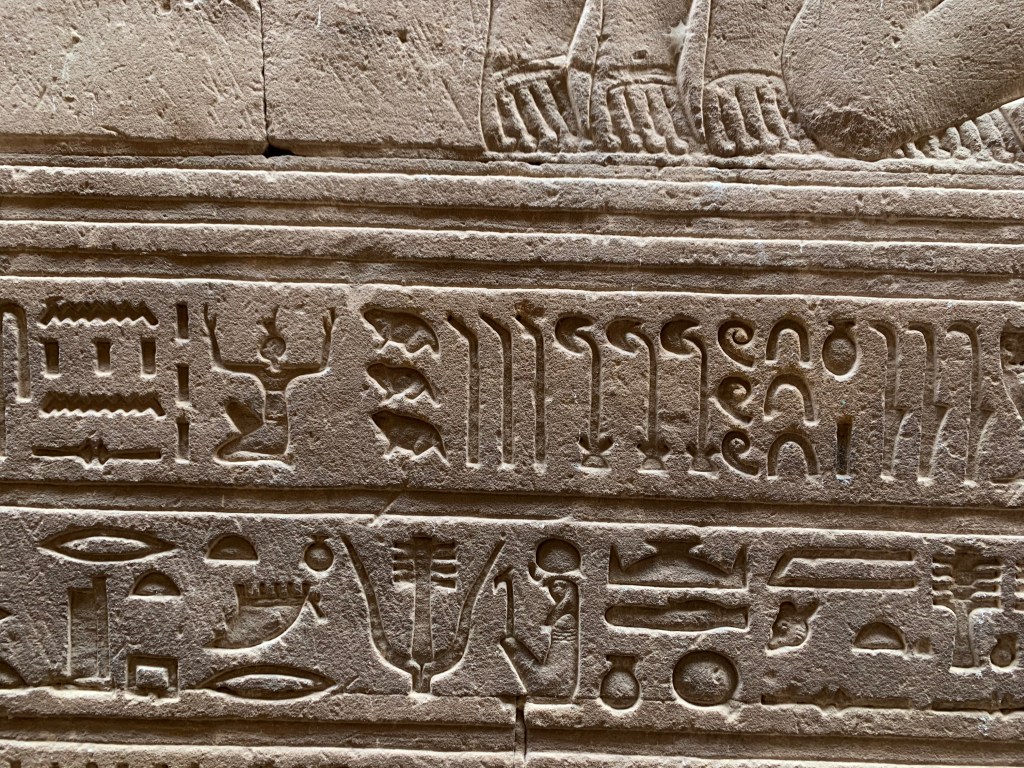

The ancient Egyptians used two kinds of alphabets: hieroglyphics for the important writings (for example, in tombs and temples) and hieratic for daily use. Today we are much more accustomed to seeing the elegant hieroglyphics because more have survived, but hieratic would have been more accessible to a larger group of the population, since it was faster to write down. Below are two comparable tablets, the left one in hieratic, the right one in hieroglyph:

A third script, demotic, started to replace hieratic from about 700 BC, until both scripts disappeared in about 400 AD, replaced initially by greek and latin, and later by arabic.

Hieroglyphics were a mystery for the next fourteen centuries, until their meaning was rediscovered in the early XIXth century, which unlocked our understanding of ancient Egypt. Today, scholars are able to read hieroglyphs in the same way as you and I read English. Watch our guide read the inscriptions on one of the many temples we visited:

Hieroglyphic writing was also used to record numbers, as in this example showing “more than three million”:

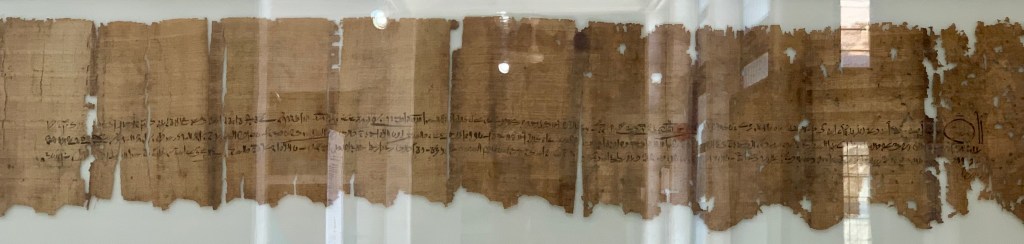

The most common way to record writing in ancient Egypt was on papyrus, a sturdy paper made from the fibres of a plant that grows in the region of the Nile’s delta. The papyrus plant was abundant and could be transformed relatively easily into very resistant paper, which in Egypt’s dry climate, stayed perfectly in shape forever.

When the Greeks and Romans came into contact with the Egyptians, they were fascinated by papyrus, but quickly discovered that it disintegrates quickly in areas that are more humid. In Europe, parchment (made with skin of animals) gradually replaced papyrus. In Egypt, it was the main support for writing until it was replaced by paper from China, from the 8th century AD onwards.

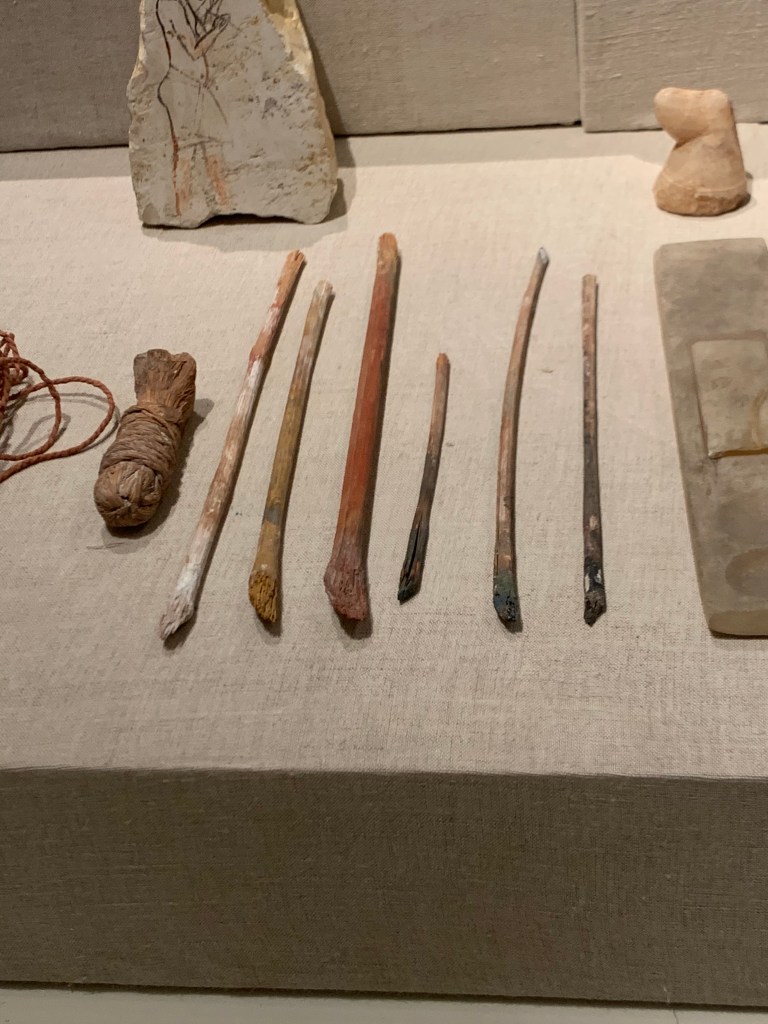

Brushes were used to write on papyrus, mostly using black and red ink.

Temples often had special rooms set aside for the preservation and storage of papyrus rolls, as in Abu Simbel:

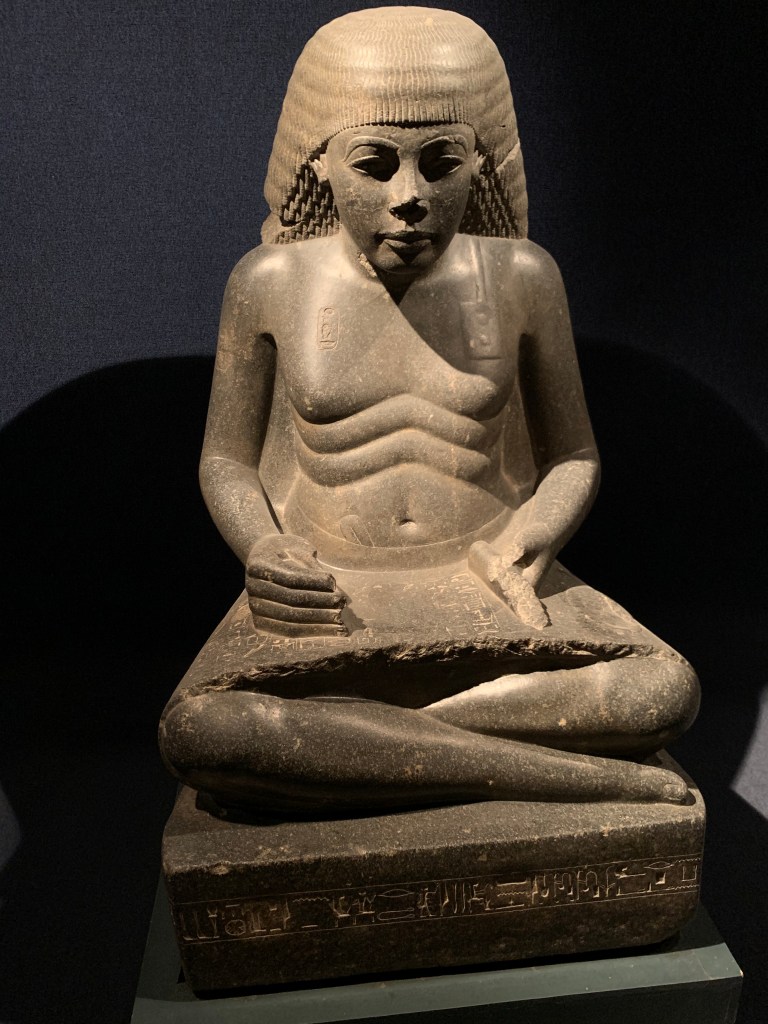

Scribes in ancient Egypt were in a privileged position. They did not have to do hard manual labour and were well paid by their patrons, who often were unable to write. In statues, they are often represented with thick pleats, a sign that they were well fed.

Despite Ramses II’s intense disapproval that a woman, Queen Hatshepsut, had ruled the nation, the ancient Egyptians lived in what was quite an egalitarian society. This is evidenced by paintings and sculptures where men and women are regularly represented as equals.

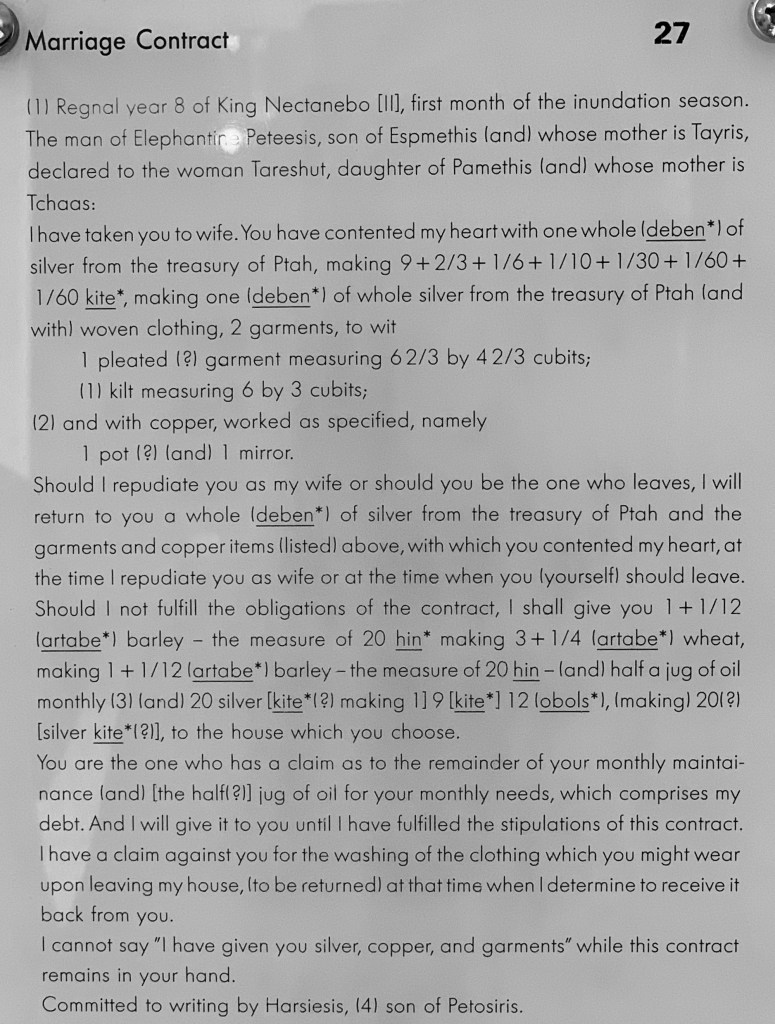

The following marriage contract, dating from about 350 BC, makes it clear that in case of divorce, husband and wife will be treated exactly the same. It’s also clear from the document that women were free to repudiate their husbands. In fact, divorces were quite common in ancient Egypt, and they were often initiated by women.

The ancient Egyptians ate twice per day. In the morning, it was mostly bread and beer. The evening meal was much bigger and consisted of vegetables, meat and more bread and beer. Banquets, which began in the afternoon, were by no means uncommon.

Ancient Egypt was a sophisticated and refined society, where music was played regularly and where the use of cosmetics and jewelry was widespread.

These remarkably well constructed harps, dating from about 1500 BC, would have been brightly coloured. The harp was played alone or in an ensemble, including instruments such as clarinets, flutes and even trumpets, accompanied by tambourines and brass cymbals, among other instruments.

Here you see a large variety of cosmetics and mirrors used in ancient Egypt. The mirrors were made with polished brass. The hair pins (bottom left) are similar in form to what we would use today.

Both men and women painted their nails:

The quality, variety and sheer beauty of the jewelry produced by the Egyptians over 3500 years ago is just mind-boggling. Below is a small sample of the beautiful objects we saw during our museum visits.

To produce the many wonderful pieces of jewelry, as well as the carvings and paintings in monuments, the ancient Egyptians worked in guilds and specialised schools, which transmitted their knowledge from generation to generation. The large variety of raw materials used were sourced from many different countries, often located far away from Egypt, through well-organised trade routes. The workers were sometimes grouped in large housing estates, such as the one below, which was recently unearthed. It shows the scale and complexity of such a settlement, the one you see here dating back to 1500 BC.

The discovery in 1885 of a workers’ village at Deir el-Medina (shown below), improved to a very large exentent the knowledge and understanding that we have today of ancient Egyptian work practices. By offering a unique testimony to life in the New Kingdom(1550 – 1069 BC), including the workmen’s houses, documentary and literary texts and drawings on limestone flakes, Deir el-Medina provides information not only about everyday life but also about administrative and economic matters, art, literature, social relations, and domestic, religious and funerary architecture of the time.

Interestingly, gold was considered in Egypt as less precious than silver, because it was rarer. The vase below, in silver and with a beautifully decorated golden handle, would have been more precious to the ancient Egyptians than the cups in solid gold surrounding it.

The refined craftsmanship in ancient Egypt sometimes defies belief. Below are a few examples of work, all of it created over 3000 years ago. We use the same type of stitching today:

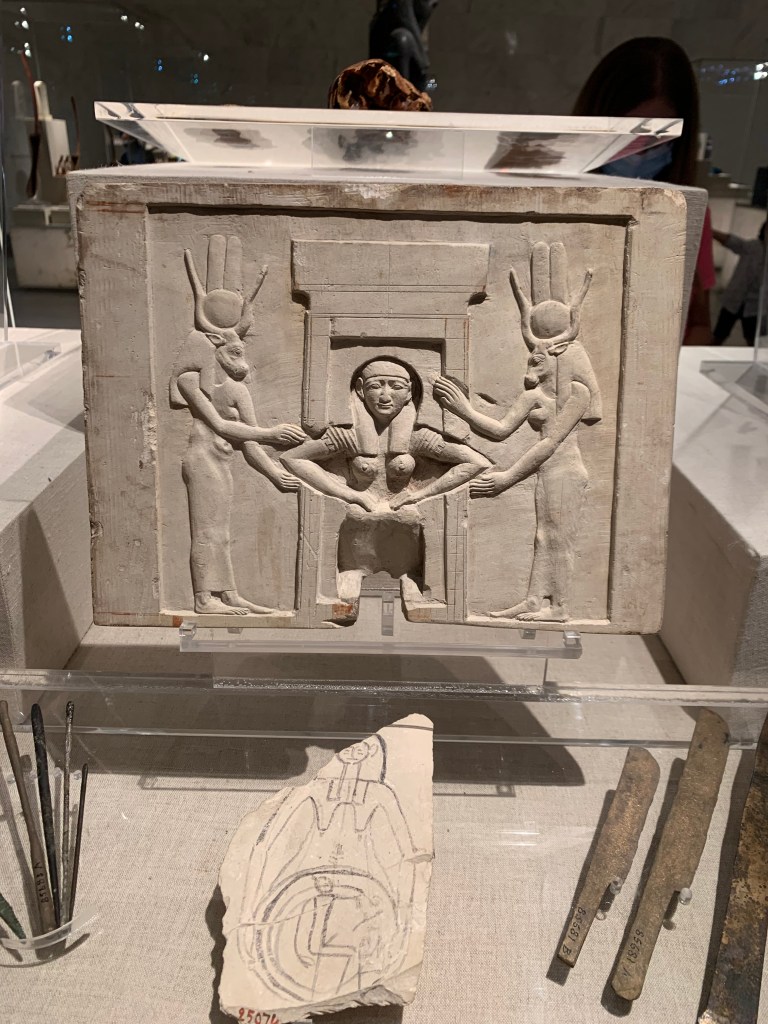

The ancient Egyptians had a very clear understanding of obstetrics, certainly a lot better than Europeans had 3000 years later. This sculpture and the drawing below, shows childbirth, and a description of the baby’s position in the mother’s womb:

The Egyptians used a so-called Nilometer to estimate every year the size of the river Nile’s flooding. This was subsequently used to calculate tax revenue:

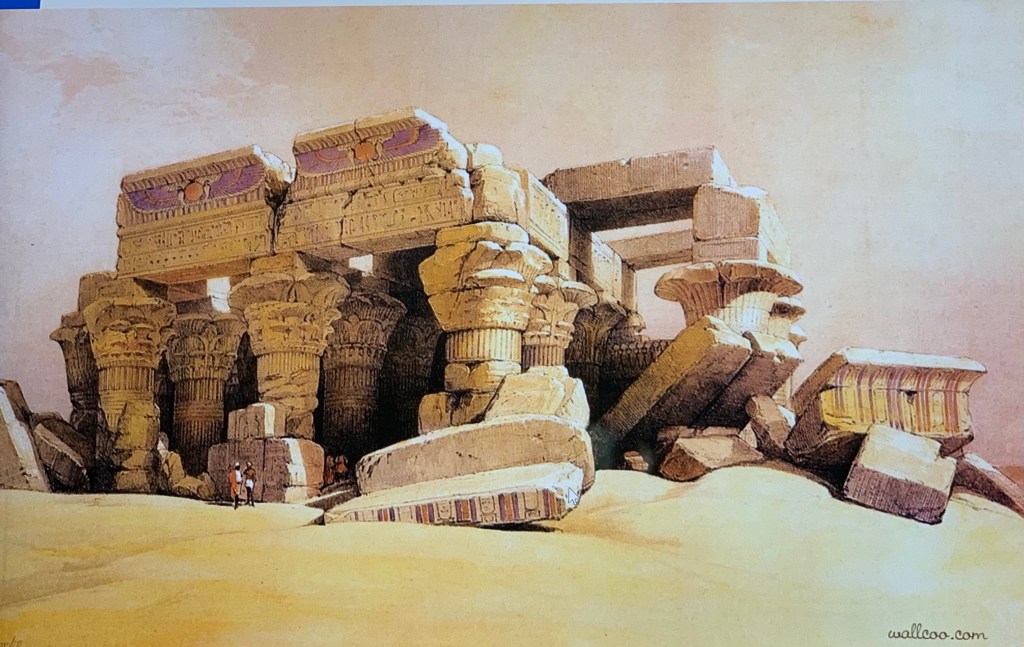

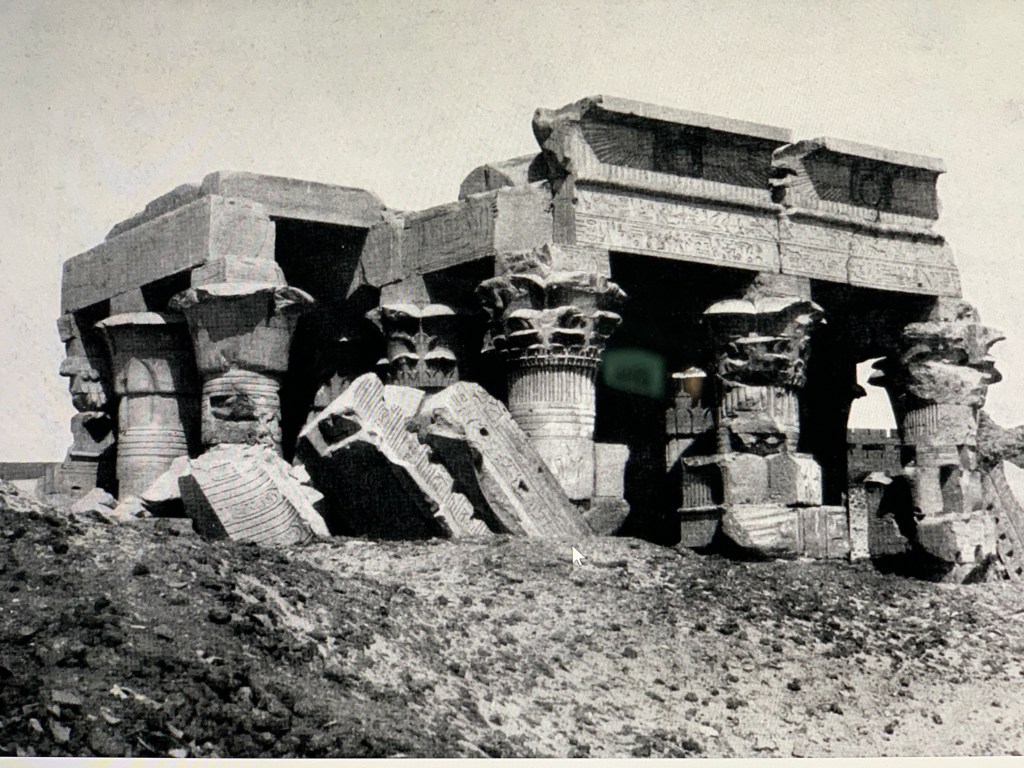

The ancient Egyptian civilisation, which (with ups and downs) had flourished for more than 3000 years, began to gradually crumble from about 1000 BC onwards. Initially, the foreign invaders (Assyrians, Persians, Nubians and later Greeks and Romans) who conquered the land, blended into the strong local culture without leaving significant traces. In fact, some of the most impressive temples still visible today were built between 300 BC and 300 AD, when Egypt was under Greco-Roman occupation.

Some of the temple ceilings have been blackened by the use of torches in modern times. A new technique developed by Egyptian specialists, is now allowing for the removal only of the black colour, allowing for the restoration of the wonderfully coloured ancient paintings.

During this time, the foreign rulers had themselves portrayed in the same way as the former Egyptian kings had, and the Egyptian language and cultures were, to a very large extent, preserved. Many of the Egpytian gods were taken over by the Greek and Roman occupiers, to the point where one of the most important religious movements in the Roman Empire at the beginning of the first century AD, was the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis.

All of this changed in the early IVth century AD, when Roman Emperor Constantine converted to christianity and it became the empire’s state religion. From then on, and until the arrival of islam at the beginning of the VIIth century AD, the Christians destroyed what they could of the ancient Egyptian beliefs and civilisation.

The buildings, the temples, the statues, the inscriptions, many of which had suriveved for over 3000 years, were, over the next two or three hundred years, systematically defaced or forcefully transformed into Christian monuments. The many beautiful temple carvings that appear defaced today, are the work of the christians during the IV to the VIIth centuries, who acted with a frenzy reminiscent of the Taliban in our times, who in the name of their religious beliefs in 2001 blew up millennial-old giant buddhist statues in Afghanistan.

The early christians constructed very little during this time, but inserted their signs wherever they could, and transformed many of the ancient buildings into rudimentary churches.

It didn’t take long during the christian era for the hieroglyphic writing itself to be banned and forgotten, and from the IVth century AD onwards, until the XIXth century when it was rediscovered, the ancient Egyptian civilisation fell silent.

The Arabs, when they conquered Egypt in 641 AD, introduced islam, but allowed the christians freedom of worship. They did order that the christian temple desecrations should immediately stop, and requested that the ancient Egyptian civilisation be studied, but it was in many cases too late. The great Egpyptian public buildings gradually began to disappear under the sand, only to be rediscovered by the Europeans in the late XVIIIth century

Starting in the 1960’s, Egypt, with the help of the world community, mobilised itself to help preserve the ancient monuments, some of which were either submerged or were threatened with being submerged by the construction Aswan’s two dams.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the absolutely remarkable move of Abu Simbel in 1966/8 and in the more recent rescue of the beautiful Philae Temple close to Aswan, submerged from the early XXth century onwards and then entirely transposed to a nearby island in the 1980’s. The entire site was carefully cut into large blocks, dismantled, lifted and reassembled (inside and outside the mountain) 500 m down the river, in one of the greatest endeavours of archeological engineering in history.

The Arab conquest of Egypt at the beginning of the VIIth century happened with relative ease. At the time, what was left of the Eastern Roman Empire, was very weak, and there were few, if any battles fought, before Egypt became part of the Rashidun Caliphate.

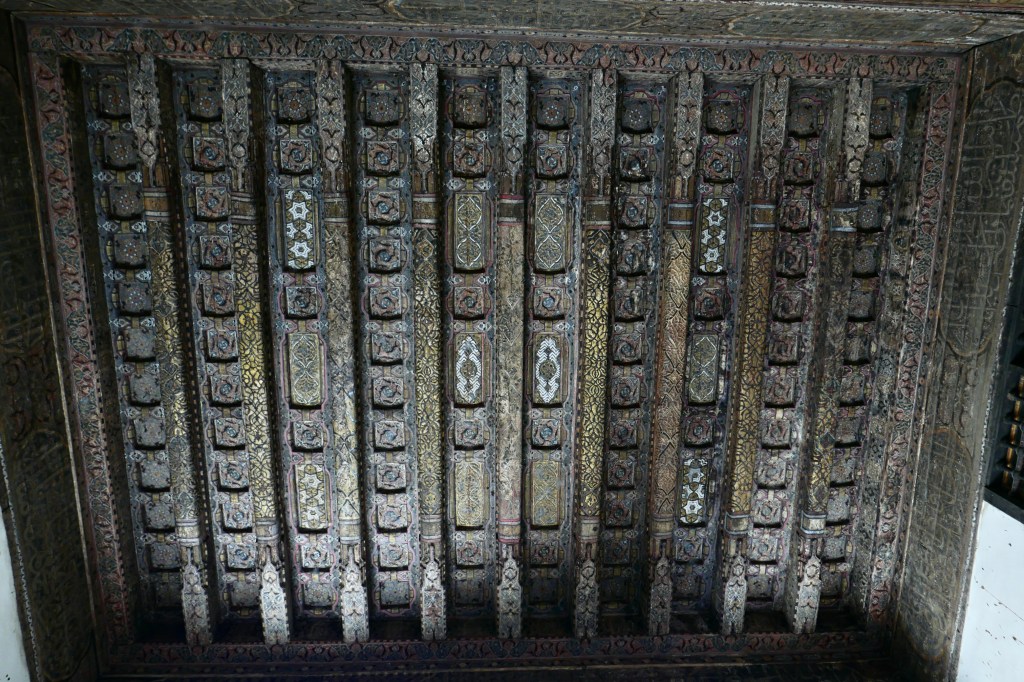

The Arabs gradually constructed magnificent public and private buildings, which are mostly visible today in Cairo, the new capital built by the conquerors from the VIIth century onwards.

The desire for a certain douceur de vivre is evident in the architectural design of the internal rooms and beautiful interior courts designed for the homes of the wealthy from the XIVth century onwards.

As in other parts of their vast empire, in Egypt freedom of religion was tolerated by the new Arab rulers, and islam was introduced only gradually. It took centuries before the majority of the population became muslim.

Today, close to 90% of Egypt’s population is muslim, the rest are Christians. There are no visible tensions between the two communities. Our visit coincided with two important religious events: the christian Easter and Ramadan, the annual month-long muslim fasting period. Both events were celebrated within their respective communities, but also on the streets, and it was clear from what we saw and heard, that there was complete tolerance and respect for these events by each religious group.

We were particularly struck by the adherence to Ramadan. More than 80% of Egyptian muslims each year fast during thirty days, which means that they don’t eat or drink from sunrise (about 3.30 am) till sundown (about 6.30 pm). They still continue with their daily duties, and this can be very hard. There were days when we walked with our guide for five or six hours, in the middle of the day, and under the most intense heat, and he never had a drop of water, while we drank more than two or three liters to survive.

In the evening, just before iftar (the meal eaten by muslims just after sunset), families will congregate at home or in restaurants, lay out food and drinks on the table and then wait for the official ending of the fast to be announced before they begin to eat or drink. We were often at restaurants at this time, and were struck by the patience of old and young, who sat quietly at their tables, looking but never touching the food, until the muezzin announced the end of the daily fast. We often felt embarassed to be eating and drinking in front of everyone else who was fasting, but no one minded, the waiters served us and in every way encouraged us to eat and drink.

We were greatly impressed by this collective show of both self-restraint as well as tolerance towards non-fasters like ourselves, but also of non-fasting muslims. The practice of religion in today’s Egypt is considered a private affair, we heard everyone say this, and saw no sign that this wasn’t indeed the case.

Food in Egypt is plentiful, inexpensive and delicious. The Egyptians not only enjoy good food, they also like to share it. It was difficult for us to explain to waiters and chefs in restaurants that the quantities we were being served were too large for us and that we were embarassed to leave food on our plates. All they wanted to hear was whether we liked the food or not, and if we did (which was invariably the case), a great sense of pride would invade the staff, followed the words: Please, please, have more! We cannot think of one meal we had in Egypt which was not delicious and in every way satisfying.

Charity is an important theme in islam, and during the month of ramadan it’s very visible at sunset, when you frequently see people on the street offering food or drinks to passersby. We were regularly invited by perfect strangers to enjoy their meal, even though it was perfectly clear that we had not fasted or were muslims.

At ramadan, during the day and the late hours of the afternoon, there is not much activity visible in the towns and cities, but soon after sunset, the streets burst with life and everyone seems to have something in mind that they must urgently buy.

In most towns, there are few crossing paths and even fewer stoplights. And there seem be no traffic rules, neither for pedestrians nor for cars. However, there appear to be few traffic incidents and everything just flows, as though choreographed by an invisible hand.

Despite the large crowds and the tumult, the incessant honking of the motorcycles and the tuk-tuks, no one steps on anyone else’s feet and we always felt in complete safety, no matter what back alley we took.

Muslims pray five times a day, but they don’t have to do so in mosques. Neither does the prayer have to be led by a religious figure. So it’s not uncommon for individuals or groups of people to gather on streetcorners to pray together.

There’s no question that islam, as practised in Egypt, leads to a strong sense of identity and community amongst the vast majority of the population. Many of the muslims we met explained to us in great detail how their religious beliefs helped and guided their existence, and how the rules and practices established by the Profet Mohammed served them in their daily lives.

While many conservative ideas (like the total repudiation of homosexuality) seemed abhorrent to us, we were struck by the complete acceptance of other points of view, both within the Egyptian community (where we also spoke with non-practicing muslims) and towards us. We did not in any way sense that islam, as practiced in Egypt, was either forced on people or that it was being proselitised towards people like us. What we felt, was that the people who practised it daily (the vast majority of the population) saw it as a very welcome way of life, which they voluntarily and eagerly agreed to.

Nowhere was this clearer than when we discussed, often at length, the muslim tradition of women being covered in the presence of non-family members. What we heard (and clearly saw) was that most women voluntarily covered their hair (and sometimes their faces), and wore long and loose clothing, because they felt that it helped them protect their privacy. It’s interesting that the same women who are covered will have no problem enjoying TV shows where most of the greatest Egyptian stars appear uncovered. This acceptance of other lifestyles or points of view was something that really struck us in Egypt.

On the political front, it surprised us to see how many people we met were supportive of the removal of the Muslim Brotherhood and its democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi by the armed forces in 2013. Almost everyone we met had voted for the Muslim Brotherhood, but they all, in unison, said that once in power, the party had severely mismanaged the government. Over and over, we heard the same message: “They tried to divide us and when in government, they were incompetent”. Most Egyptians we met felt first and foremost Egyptian, no matter the religious group they belonged to, and felt offended by the “you are with us or against us” attitude of the Muslim Brotherhood. In fact, we hardly found anyone who didn’t support Al-Sissi, the head of the armed forces and current president.

Wherever you go in Egypt, there are checkpoints, even in the remotest areas. And it’s clear that the military installations are huge and vey well equipped. When we pointed out the cost and complexity of this, no one seemed to mind. Everyone we met seemed to think that this was a small price to pay compared to the chaos in Egypt during the time when the Muslim Brotherhood were in power.

In addition to offering extraordinary cultural and historical experiences, a trip to Egypt is also unforgettable because of the natural scenery you see and, especially, because of the Nile.

Many writers have fallen in love with the Nile and we could see why. During the first part of its very long trajectory, while it traverses Uganda, Sudan and Ethiopia, it’s a river that has many rapids and is sometimes difficult to navigate. But from Aswan in Egypt onwards, it becomes a slow, meandering river, which invites to reflection and which offers stunning sights. There is little wind, the sky and the river are pale blue and the greenery you see, followed by the strong yellow colour of the desert, is just stunning. Here and there you see peasants at work and the silence is only interrupted by the occasional shouting of children bathing in this surprisingly clean river.

We spent hours on the deck of our ship, without saying a word, just looking at this beautiful scenery. Once you go down the Nile, you understand why the ancient Egyptians wished to live nowhere else, how they couldn’t imagine that there could ever be a more beautiful world than this.

Most travellers spend little or no time in Aswan, but this is a mistake. The area is full of many small islands, and we spent more than one afternoon on a small boat, just meandering about and watching the changes in the scenery as the sun gradually set.

Also close to Aswan, there are a number of sleepy Nubian villages, well worth visiting. The brightly coloured architecture is strikingly different to what you see elsewhere in Egypt.

Very close to Aswan is also the Monastery of St. Simeon. Constructed in the VIIth century AD by coptic monks, it was considerbly expanded in the Xth century and then mysteriously abandoned in the XIIIth. We were the sole visitors on the day we went and were spellbound by the silence and beautiful views of the area. If you wanted a peaceful environment in which to feel close to God, this was surely an excellent place to do so.

We stayed in several beautiful hotels while in Egypt. The absolute highlights were the Four Seasons at Nile Plaza in Cairo and, especially, the Old Cataract Hotel in Aswan.

There are two Four Seasons Hotels in Cairo. They more or less cost the same, but the one at Nile Plaza is significantly better. Our room overlooking the Nile offered breathtaking views of the city, as well as the great Pyramids. As the sun sets, the city becomes alive and you can witness from your balcony the buzzing activity below.

The Four Seasons at Nile Plaza also includes two exceptionally good restaurants: Zitouni, serving Egyptian food and 8, rumoured to offer the best Chinese food in the Middle East (they might be right, we loved it).

The Old Cataract Hotel in Aswan was built between 1898 and 1902, and has recently been beautifully restored. There is an old and a new building. We stayed in the new building, which offers spectacular views of the surrounding area and very big rooms. But the old building also has its charm.

If you’re in for a real treat, reserve one of the suites on the top floor of the old building.

A romantic evening meal at King Farouk’s corner is well worth it.

There are not many choices in Luxor, the only worthwhile address is the Winter Palace, which is a bit run down, but still quite charming. As you wander through the gardens and the large reception area, you definitely get the atmosphere of what early XXth century travel in Egypt was like.

The Abercrombie & Kent boat that took us from Luxor to Aswan was comfortable. The highlight were the excellent meals and the impeccable service. And yes, we enjoyed the dance on the Egyptian evening!

At the end of the trip we said to ourselves: there really are only two places to visit during your lifetime – Egypt and the rest of the world. We really loved this magical land and hope to be back soon in order to visit those areas (and there are a few) that we didn’t have time to explore this time.

Amazing travel report – thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

This is exceptionally informative, I really loved it! And wow, what an amazing trip…

LikeLike

What an amazing trip – thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

Great write-up well done! You may remember, my parents were married in cairo in 1943, so it has a special place in our hearts… Bravo et à bientôt!

LikeLike

Thank you John! So we’re following you around…Tanzania and now Egypt. A big hug!

LikeLike