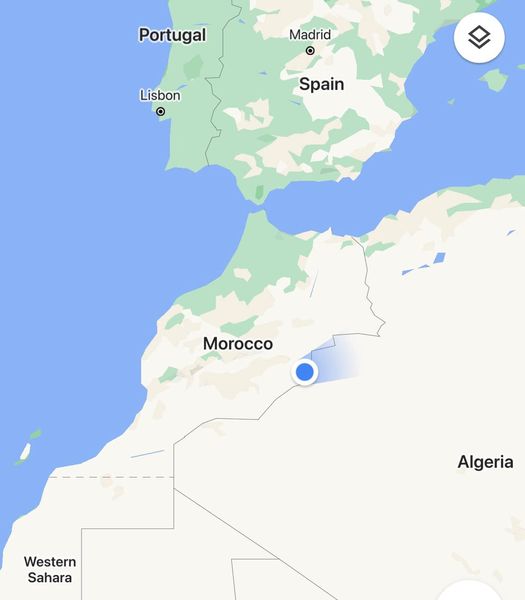

On the northwestern tip of Africa, Morocco is a large and multi-faceted country, about twice the size of the UK, which we had the great pleasure of visiting for several weeks in September 2021.

Our itinerary took us from Casablanca to Tangier via Rabat. From there we headed south to Fès with stops in Chefchauen and Volubilis. We then spent time in the Sahara, very close to the border with Algeria. The final leg of our trip was in the Atlas Mountains, Ouarzazate and the Marrakesh region.

Morocco was conquered by the Arabs in the VIIIth century, but it’s not an Arab country. To this day, about three quarters of its population is Berber (or of Berber origin), an ethnic group with a totally different language and culture.

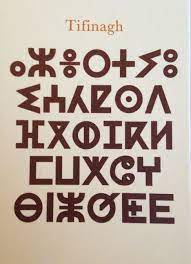

Until a decade ago, only Arabic was taught in schools and used in official business, including court proceedings. Fearful of a backlash during the Arab spring, which started in Tunisia in 2010 and swept through the Arab nations, King Mohammed VI in 2011 introduced Berber as an official language in Morocco, which now appears widely in written form across the country.

Berber is an indigenous African language, completely different language to Arabic and with its own, very distinctive alphabet.

Berbers are an ethnic group of approx. 70 million people, stretching across Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Libya and Niger, where they have lived continuously for at least 10’000 yeears.

They have a strong cultural identity and even their own flag, but we did not sense a yearning for a transnational political identity on the part of the many Berbers we met during our trip. All of them, while feeling proud of their Berber heritage, saw themselves first and foremost as Moroccans.

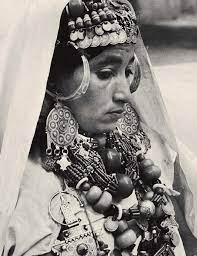

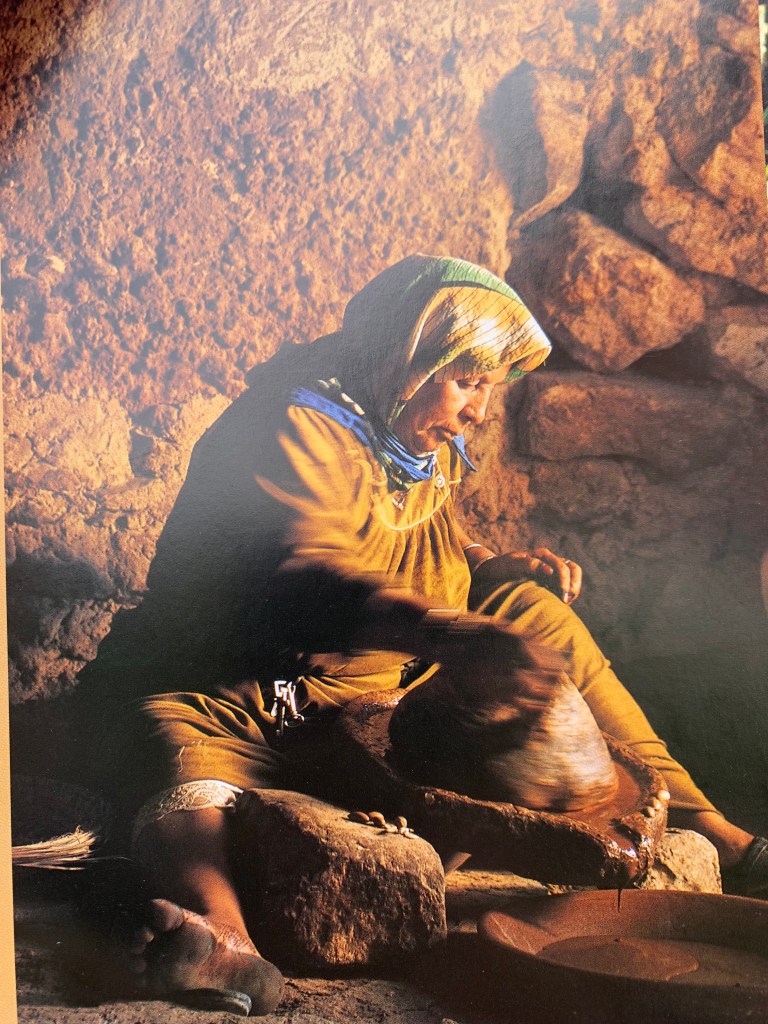

Moroccan Berbers (many of whom are nomadic or semi-nomadic) create wonderful jewelry, which not only serves the purpose of embellishing them, but also to store wealth. Silver, considered more precious than gold, is used by Berbers to create the ornaments they so proudly wear.

We were mesmerised by the variety and quality of the jewelry we saw at the Berber Museum, the Photography Museum (both in Marrakesh), as well as many other places throughout Morocco.

Not only the Berber jewellery is remarkable, also their varied and beautiful clothing amazed us.

Berber iconography is also often present on the façades of buildings. On first glance, it appears simplistic, but there is a profound message in it: there is a beginning, but there is no end, and life progresses with ups and downs, never in a straight line.

A mixture of Andalusian, Arab, Berber, Ottoman and African traditions, Moroccan cuisine is above all about art of living and, it is a women’s art: the pleasure of receiving guests and the pleasure of sharing a meal, hospitality and friendliness, slow pace of living and enjoying together the food on the table are part of that art.

In traditional families, women do the shopping and spend a large part of their days preparing meals, baking pastries and cakes and making preserves from jealously guarded recipes. Transmitted from mother to daughter through the generations, the art of cooking combines manual skills with a clever mixing of the proportions, relying more on hand and eye than on precise measurements. How much we loved to feel the fragrant scent of the orange blossom hovering in the air, and imagined the water boiling in the samovars, the tajines on the fire and the couscous steamed in three separate steps on Fridays – the day of the week that couscous is traditionally made – behind the thick walls of the medina.

Couscous is the most convivial dish, served on traditional festive occasions such as a birth or a marriage or after a funeral. Presented as a dome- shaped mound on a hollow dish and moistened with stock, it is covered with meat and veggies, depending on the season and the region where it’s prepared. Making it is a real art. Swollen in the steam of the cooking pot and then tossed by hand, the grains must melt in the mouth. Tasting couscous, whether is adorned with fish, lamb, chicken or vegetables is an utter delight for all the senses.

A pleasure for the eyes, the dishes are arranged artistically on the table and they come in a succession of colourful salads, pastilles (a kind of meat pie), grilled dishes, fish or a tajine.

Made with meat, chicken, fish or veggies, combined with olives, prunes, apricots, almonds, raisins or preserved lemons, the tagine is cooked slowly in the thick earthenware dish from which it took its name.

Tajines are accompanied by bread, often used as a spoon, which is the Moroccan staple food, consumed in large quantities at every meal and sold in dozens of stands, and at all hours of the day. As we wandered through towns and villages, we had trouble resisting the temptation of stopping at every street corner to eat the delicious Moroccan bread!

In every house the visitor is greeted with a cup of tea and no meal is complete without the ritual of mint tea. Green tea, introduced by English merchants in the mid XIXth century, is always served with springs of mint tea that are barely bent – they are never cut – before being added to the teapot. After the tea is brewed, stirred at great length, smelled and taste by the person preparing it, it is then served in small narrow glasses.

How many times were we hypnotised by the ritual of pouring the beautiful amber-coloured drink from raised teapots. No drop ever falls outside the narrow glasses and a foam of tiny bubbles forms on the surface of the tea. The more experienced the tea “master” is, the more bubbles are created on the surface of the tea.

We of course also ate bread every day, for every meal, and tasted dozens of variants, but nowhere was it better than when we visited a Berber nomad family in the south of Morocco.

Baked in a traditional oven made out of clay, built on the ground and reconstructed at every new stop, cooked with firewood from local shrubs, and accompanied by traditional Moroccan mint tea and olive oil, it had an unforgettable, crisp taste. Our meal was served in the simplest of tents and accompanied by the warmest of welcomes. Smiles under veils and simple, unrushe gestures, accompanied the hearty welcome.

Hot, stimulating and sweet, spices give Moroccan cuisine the indefinable flavour that makes it unique, as long as they are used in the right quantities. Bought loose at the markets, they enhance meat and vegetable dishes and add flavour to pastries and cakes.

The Moroccans use turmeric, saffron, cumin, ginger, cinnamon, sweet paprika and (sparingly) hot chilli pepper, which are combined in endless variants, resulting in very colourful and tasty dishes, which we had the opportunity to learn how to prepare during a cooking class in Fès.

Tajines and couscous are always accompanied by a large variety of salads. Coriander, used as a fresh herb, is ubiquitous in Moroccan cuisine, as is flat-leaved parsley. The markets, even in the most distant villages, are filled with fresh vegetables and unsual meat cuts (including bulls balls), for which Morocco is famous.

In the Moroccan tradition, eating somewhere else than at home is rare. This is because few restaurants can compete with the quality of home cooking and it’s the pride of every woman to provide for her family a first-class home meal.

The cuisine of Fès, the imperial city, has spread throughout Morocco and is the inspiration of numerous recipes. It is a cuisine characterised by dishes that have simmered for hours and have sophisticated flavours.

Even before you sit down down at any restaurant or café, olives and pickles are put on the table, which are eaten at any time of the day or night.

For breakfast, Moroccans eat the omnipresent bread, which they soak in olive oil. Or, alternatively, they will cook eggs in fat and small pieces of meat, which are sold in every market and are ready to use.

Desert in Morocco is not an elaborate affair. It’s either fresh fruit or dates, although some shops do sell bite-size sweets in a large variety of forms, as you would find in many other Middle Eastern countries.

The palm tree does not bear dates naturally. Neither wind nor insects are sufficient to carry the pollen to fertilise it. So people use a form of artificial insemination.

In late March or early April a specialist gathers from the centre of the male palm tree, the part that encloses the pollen. He cuts it open and slips it into the female date palm “organ”, then secures it with a ribbon of palm to protect it from the wind. The ribbon will break once fertilisation has taken place and the date harvest can begin at the end of the summer.

The happiest creatures in Morocco are not people, but cats. In every restaurant, every hotel and on every streetcorner, there are cats. None of them seem hungry, most of them have shining furs and more than once we saw passersby stopping to gently caress them.

Shopkeepers habitually reserve special corners for them and when the day is over, you see cats roaming all the dark alleys of medinas, feasting on the rests of everyone else’s meals.

Abundance is the word that appears to drive sales in Morocco. In the souks and markets, stands seem to compete with each other on the basis of how much products they can fit into the smallest of areas. This, accompanied by the large number of people, animals and vehicles of all kinds that roam through the narrow alleys, make for a lively, but sometimes tiring experience.

Enveloped by a sea of colours and smells, the visitor who ventures into a souk is faced with a wonderful, magical world where the light is subdued as it filters through the bamboo trellises or the wooden latticework shielding the alleyways from the heat of the sun.

The trading heart of the big medina, the souk is usually organised in a hierarchic fashion around a major mosque. Near the mosque itself are the traders in more luxurious, goods such as goldsmiths. Further away, the products become more commonplace. The tanneries and blacksmiths, the most polluting and noisiest activities, are concentrated near the ramparts. The practitioners of each trade – weavers, carpenters, cobblers – have their own street, lined with tiny stalls that are closed at night with shutters. Craftsmen have preserved their skills by tirelessly repeating the same movements, passed down from father to son or under the benevolent eye of a master craftsman.

The souk is the centre of attraction, a meeting place where transactions take place and necessary supplies are bought. It is in the souk that debts are settled and Morocco is still very much a cash society – people pass by each other and like through a wonder, sometimes quite large amounts of money are slipped from one hand to the other. We often wondered: how do people know that they will meet each other and how come that they are holding in their hands the right number of bills?

But not everything is hustle and bustle in Morocco. Even in the midst of the most populous old towns (called medinas), there are plenty of quiet spaces. These are usually found inside the riads or dars.

The Moroccan home is a closed universe, inaccessible to the outside world, with luxury and comfort not visible from the exterior. In contrast, the interior reflects the prestige of the master of the house: the number of outbuildings and loggias, the size of the internal garden courtyard (always present in a riad) and the elaborateness of the decor depend on the prosperity and social rank of the owner.

The sobriety of Moroccan house’s exterior contrasting with its ostentatious lush interiors made us think of the houses in Calvinist Geneva – Calvin did not have anything against wealth, but he frowned upon the display of wealth, which explains why the streets of Geneva’s old town (like those of Moroccan medina’s) appear so austere.

The riad was originally an enclosed garden of Andalusian origin, divided into four parts, with a decorative fountain in the centre from which water endlessly flowed. A form of reconstituted oasis, in the Mulsim tradition, it prefigures the celestial paradise. In Islam, paradise or the garden of Eden, is described as the source of four rivers. In a riad, water is always present in the form of a fountain or basin with a jet. By extension, the riad has given its name to the whole house surrounding this enclosed garden with its straight paths.

A welcoming, friendly place, the riad was designed to receive a large number of people. Paved with marble or zellig mosaics, the courtyard is sometimes surrounded by a beautiful covered arcade offering protection against the sun or bad weather and flanked by several long rectangular rooms.

More modest than a riad, a dar (‘house’ in Arabic) is the commonest type of residence in the medina. It is entered through a narrow, winding corridor that does not immediately reveal the secrets of the house. The building encloses a square, open air courtyard that allows fresh air to circulate inside and which is surrounded by high walls flanked by long narrow rooms. Despite of the fact that the courtyard of a dar does not have a garden, it remains as mysterious and sensual as a riad.

The Moroccan interiour courts are true havens of peace and we spent many a time just sitting on a bench enjoying the quiet, only disturbed by the sound of a water fountain or the songs of birds traveling from one courtyard to the next.

A spring of water at the heart of the garden is common to all Islamic green spaces or courtyards. The continuous spring fosters serenity and contemplation. Water is given great importance at the spiritual level in the Muslim world, witnessed by its use in ablutions, the ritual cleansing through which the believer readies himself for prayers five times per day. Water is portrayed as a symbol of life: in the Qur’an, springs and rivers appear as a sign of divine grace, and heaven is described as a “garden in which endless streams flow”.

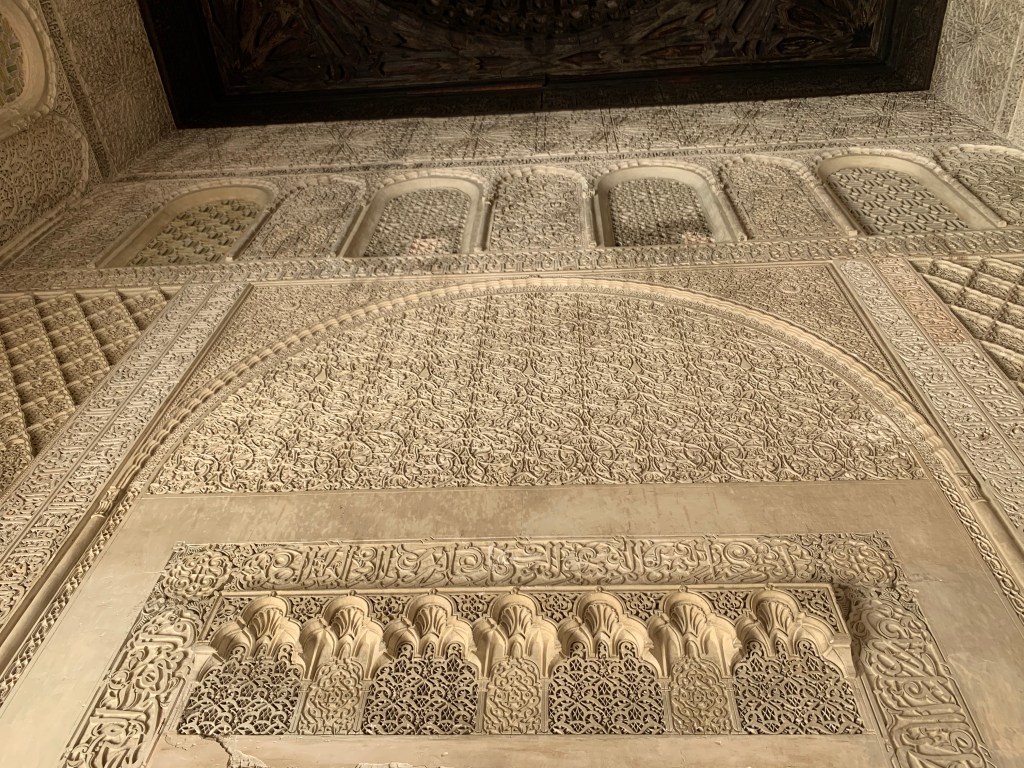

The intricate and beautiful geometric figures that are omnipresent in Moroccan art, add to the sense of serenity of the interior courtyards and buildings.

Morocco’s houses of worship are also impressive, with the monumental King Hassan II mosque in Casablanca simply incredible (it’s the largest building in Morocco and the third largest mosque in the world). We had the rare privilege of visiting it on our own.

Towards the outside, islamic architecture prones sobriety. From the simplest of homes to the grandest of palaces, it is simple, whitewashed façades that greet the visitor, with one exception: the doors, which are magnificent.

Wherever you go in Morocco, you are amazed by the beauty and intricacy of wonderfully decorated doors. Inside homes too, doors are often magnificently carved out of expensive wood, which was transported already in the Middle Ages to Morocco at great expense from far-away Lebanon and Syria.

Not all architecture in Morocco is inspired by islam. In the northern cities, especially in Tangier, there is strong evidence of Spanish influence.

In fact Tangier, the northermost city, from which you can see the coast of Spain, has been for many centuries a crossroads of cultures, a transit place for Africans and people from the Middle East towards Europe, and vice-versa. We enjoyed Tangier’s quiet streets, the beautiful esplanade by the coast, the cafés, the great food and the magnificent views of the Mediterranean from its hilltop medina.

Jews have lived in Morocco from time immemorial, but they really started pouring in after 1492, when the kings of Spain (and, soon after, the Portuguese) expelled them. The Arab nations welcomed the Jewish population because the sultans knew that with them came knowledge, hard work and a grateful group of people, who were shocked by the way in which they had been treated in their native homeland.

Many of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews settled in Morocco and integrated very well. It was only half a millennium later, after Israel was created, that Moroccan Jews began to leave the country.

At its height, in the 1950’s, there were 350’000 Jews living in Morocco. There are only about 3’000 Jews left nowadays, but we witnessed the Jewish heritage throughout the country.

One of the striking things that the Jews brought with them was the colour blue. In Judaism, blue is associated with divine protection, so the new arrivals began to paint their houses in this colour. Soon the rest of the population followed and today, in many cities and towns in northern Morocco, blue is the all-pervasive colour.

Chefchaouen encourages strolling. In this charming little town in the Rif mountains, whitewash mixed with large blue surfaces, creates a feeling of coolness and, as the belief goes, deters insects. The narrow back streets play with the light as they dive below the arches that link the houses to each other, while the whitish reflection simulates coolness.

The Jews also brought to Morocco talismans and symbols, which gradually blended with the local iconography. We discovered true treasures at a 500-year-old synagogue in Ouarzazate, which we had the good fortune of visiting on our own and guided by the sole Jewish family left in this town.

In Ouarzazate we discovered the shop of Fernando Vacaflores, a Chilean photographer who settled in Morocco and offers photography tours to confirmed and aspiring photographers (https://www.vacaflores.com/). We were impressed by his excellent work.

For the Romans, what is now Morocco was called Mauretania Tingitana. It was the western frontier of their large empire, and as such an important area because of security (to prevent African tribes from moving north) and trade (it was from this region that they sourced ivory, slaves, gold and lions for their arenas).

In line with the importance of Mauretania Tingitana, the Romans built a number of fortified towns and cities, the most impressive being Volubilis, its capital, which by AD200 had over 20’000 inhabitants.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Volubilis gradually lost importance and was eventually abandoned. Its ruins were only rediscovered by the end of the XIXth century and it has now been partly excavated. We were very impressed by what we saw: remnants of exquisite, large homes, baths, aqueducts, beautiful mosaics, triumphal arches and impressive temples. The views from Volubilis are also breathtaking.

The north of Morocco is lush and very green, even at the end of the dry season. The feeling is one of plenty – it looks like everything grows here and that the land is incredibly rich.

Then, as you move south, the Atlas mountains hit you. They are steep and dramatic. The contrast between the high peaks and the fertile valleys is striking.

On the southern side of the Atlas Mountains, as you enter the vast expanse of the African desert, the scenery changes dramatically. One-third of Morocco is covered by a desert that stretches from the foothills of the Atlas Mountains to Mauritania, from the Algerian border to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Sahara is a place of silence and solitude like we had never experienced before. Far from the noise of the world, we entered a wonderful new dimension which we cherished and embraced spontaneously. Only the occasional breeze in the middle of the day broke what was otherwise deafening silence.

But the Sahara isn’t only silence, it is full of magnificent colours. The dunes change hues almost by the minute, and sunrises and sunsets are simply unforgettable.

You would think that the desert is well, a desert, but in fact it’s teeming with life. If you look carefully, there are everywhere signs left by foxes, mice, lizards, beetles, sand fishes and vipers, all creatures of the desert.

To merge with the background, animals have adopted the colours of sand and earth: the dromedary with its ochre coat, the gold coloured jackal, the pale towny gazelles or the golden brown fox. It’s the plants that impressed us the most – how they managed to survive, sometimes thriving in an environment where two or three years can go by without a drop of rain.

A camel ride at sunset was one of the most memorable experiences of our trip. These delicate and highly sensitive animals, famed for their sobriety and good memory, move with incredible grace through the dunes. They perfectly accompany the all-encompassing silence. And yes, they love to be caressed.

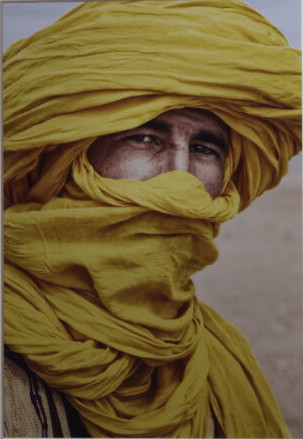

Most of the Berbers we encountered in the Sahara were wearing turbans. We wondered what it was like to carry one. It turned out to be difficult to put on (Pedro couldn’t do it without help), a bit heavy (his was 10m long), but not unconfortable. But it’s clear that during a sandstorm (which we didn’t experience) a turban would be of great help.

One of the most unforgettable things about Morocco is its light and colour. It was the great French painter Eugène Delacroix who, during his travels to this region in the first part of the XIXth century, first uncovered for Europeans the incredible luminosity of this region and transposed it into paintings that would so greatly influence the impressionist artists.

We spent many hours just enjoying the changing hues of Morocco’s wonderfully crisp atmosphere.

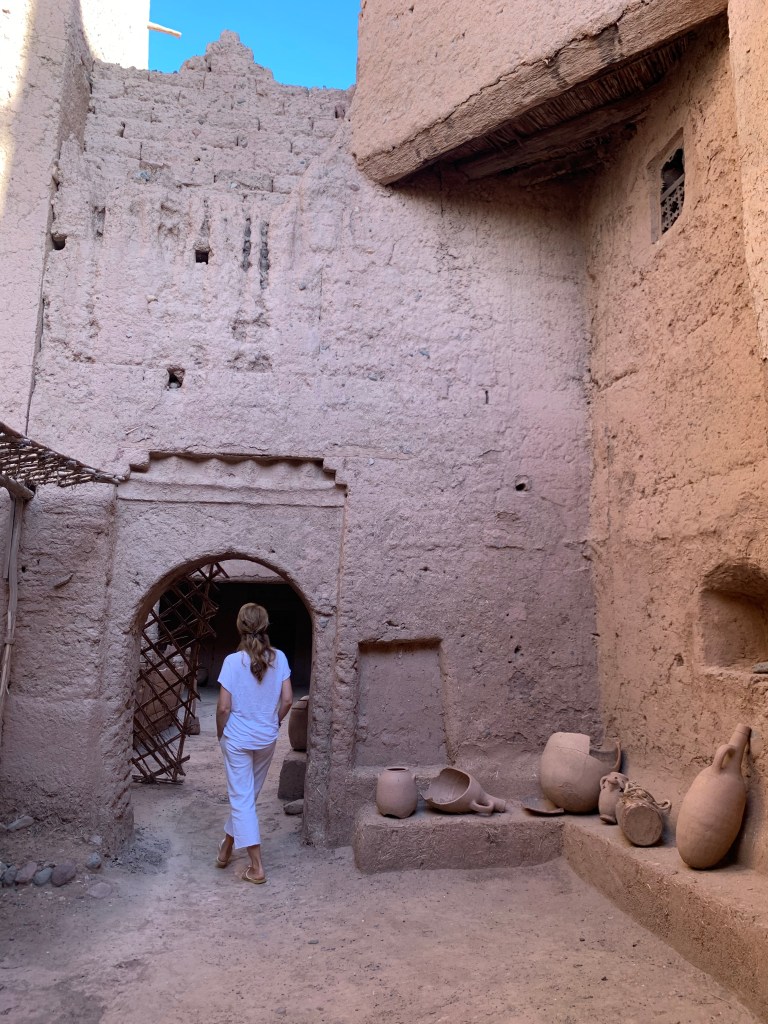

The Moroccan houses are traditionally built in mud. The walls are very thick and there are few windows, but the strong light still results in sufficient indoor clarity. The result are homes that are cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

With urban planning inexistent, and the winter rains often destroying part of the walls, requiring almost yearly re-building, the traditional Moroccan village offers a conglomerate of meandering, mysterious and incredibly charming paths.

To the north-west of Ouarzazate, the village of Ait Benhaddou, built against a hillside of pinkish sandstone is a jewel of adobe houses and majestic kasbahs (the ancient patriarchal dwelling) that has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987. The harmony and beauty of this ensemble lies in the myriads of alleys and interconnected houses and kasbahs made of red and ochre adobe, topped with towers and crenellations.

In the mountain villages, the collective granary was the foundation of the communal organisation that was so vital during the period of intertribal conflicts. Built in adobe, it contained the harvest of each family, and also weapons, jewels and other valuables. Each family had its own box and key and the granary was guarded by a caretaker.

We stayed in seven hotels during our travels through Morocco. Here is what we thought of them:

The Four Seasons in Casablanca is modern, with nice size rooms and an excellent location, on a large and sandy beach. We stayed only one night, but it was enough to enjoy the beautiful garden and the great breakfast, from where we could see dozens of football matches being played on the sand.

Set on a hilltop, Villa Joséphine in Tangier is a jewel. It’s one of those hotels that feels like you are staying in someone’s home. Not just the objects are beautiful and the ambiance from another time, but also the staff feels like it’s been there forever (for the most part, they have).

There is an atmosphere of serenity offering a welcome contrast to the hussle and bustle of the town. You can take the beachfront path and walk to the medina from Villa Joséphine, a very nice stroll. It’s definitely a hotel we would recommend.

In Fès, we stayed at Riad Fès, a beautifully and painstakingly restored hotel located in the centre of the medina. The rooms are very nice, but they can be quite somber if they are facing the courtyard. If light is important to you, make sure you ask for a room on the upper floors or (as we had) a room facing the swimming pool.

The Merzouga Luxury Desert Camp where we stayed for two nights is not really luxurious, but it’s beautifully located, right on the edge of the Sahara, and the staff are fabulous.

At night, the meals are taken under the stars and after dinner, there is usually music and a bonfire. One of the evenings, we went for a romantic stroll in the dunes and were overwhelmed by the starry night.

Ouarzazate is not really worth staying at. The town is very small and there is not much to see. However, if you really need to stop there, there is really only one address: the Berbère Palace. It’s big and feels impersonal, but the rooms are generous. The best part of the hotel is the huge swimming pool. Don’t stay there for dinner, opt for Douyria (right on the edge of the old town) or Jardin des Arômes (in the heart of the market).

Kasbah Tamadot, one hour south of Marrakesh, is a gem. Part of Richard Branson’s group of hotels, this is one of the places we’ve stayed at that we will never forget and sincerely hope to return to.

Nestled in the hills, it offers incredible views of the countryside, a beautiful pool and great food. The whole place is full of amazing art and as you meander through its many staircases, you get the feeling of what life was like when this house (originally built in the 1920’s) was the local governor’s summer kasbah.

Tamadot is a place of such overwhelming beauty that we sometimes had trouble trying to figure out where to sit and what to look at first, so intense was the experience.

In Marrakesh we stayed at Riad El Fenn. It’s wonderfull located, just at the edge of the medina and it’s unquestionably a very beautiful hotel. You can walk everywhere in the Medina and you can equally be very fast outside of it, if you wish to walk to the Royal Mansour or La Mamounia, to have lunch, tea or dinner. It’s also the hip place in town and the staff are really cool. The afternoon teas are memorable featuring delicious cakes and pastries. The rooftop is atmospheric and bursts with energy and life especially in the evenings.

But the emphasis is on design, not necessarily practicality: our room had no cupboards and there was little, if any place, where to put our toiletries. The showers don’t work well and none of the rooms have locks (although the staff will provide you with a padlock, if you insist).

Importantly, if light is important to you, then make sure you ask for a room on the top floor – the ground floor rooms are incredibly gloomy and you need to have the wooden shutters closed at all times (with therefore zero light entering the room), unless of course you like passersby to stare at you while you’re in bed or while you’re changing. The most luminous and generous rooms are 19, 20, 21 and 22, but you need to book in advance.

We did not stay at the Royal Mansour in Marrakesh, but we visited it, and we were amazed by what we saw. It’s a hotel like no other – the “rooms” are in fact three-storey mini-riads, built with exquisite materials; each comes with its own staff.

Royal Mansour is located in lush gardens and owned by Morocco’s king, who by building it, wished to showcase Moroccan craftsmanship. We think he succeeded!

The Royal Mansour has only one drawback: if you stay there, you’re unlikely to leave the place and will probably see nothing else in Marrakesh!

Marrakesh, which we had visited eighteen years ago, was at the time exotic and mysterious. Now, it’s just as exotic and mysterious, but it’s also hip. There are a lot of trendy restaurants and shops, featuring a great bland of Middle Eastern, European and even Asian influences.

A few of the restaurants we loved in Marrakesh : 1) La Maison Arabe for delicious Moroccan food, 2) Le Jardin for its beautiful terrace in the middle of the Medina and tasty light food, 3) Bo Zin for good Asian cuisine and splendid decor and atmosphere in the evening, 4) La Famille Marrakech for lunch and relaxed garden atmosphere and 5) the restaurant on the rooftop of El Fenn for breakfast, lunch or dinner.

As for the lovers of shopping: 1)Aya’s, for beautiful Moroccans kaftans made with the finest fabrics and care, and 2) the wonderfully curated boutique at El Fenn.

If you only have a few days for a trip to Morocco, then spend them all in Marrakesh. A short flight from Europe takes to this both relaxing and incredibly exciting town.

This report wouldn’t be complete without a heartfelt word about the Morrocan people: everyone we met was curious and had time for us, everyone wanted to share their meal and their life-story with us.

Yes, in the souks people approached us from all sides to try to sell us something, but as soon as we said kindly, but firmly, that we were not interested, we were waved goodbye with warm and friendly gestures. “May Allah be with you” we heard dozens of times.

We will be back to this charming and in so many ways enchanting country!

I am so proud of both of you!!!! What a fabulous well written report and exceptionally outstanding pictures!! All taken by you or some bought from the Chilean Photographier? Anyhow they are beautiful and and very illustrative. Abrazos Pa

LikeLike

Our friends Paul and Silvia shared w us the excellent descriptions of exotic and beautiful country of which we didn’t know much but now thanks to you wish to visit- photo and writing tops

Thank you

LikeLike

Enjoyed reading about your travels and was wishing I was there with you. They photos were wonderful. Thank you Paul for sharing your family travel log.

LikeLike

Pedro, Yoour report illuminates. Thank you and Evelyn. Eric

LikeLike

Thanks to Pedro and Evelyn for your beautifull pictures

You help my to learn about exotics countries

and culturas

Enjoy your retirement

Ricardo

LikeLike