Vietnam is one of Asia’s largest countries. With over 100 million inhabitants, it is about one third the size of the US in population terms. Although the majority of the population live in the Red River Delta (Hanoi) and the Mekong Delta (Ho Chi Minh City), it is still very much an agricultural country.

As a nation located in the middle of Southeast Asia, Vietnam offers an amazing blend of cultural richness and stunning natural landscapes. But what makes it really special and worth a visit, are the people.

For more than 45 years in the XXth century, Vietnam was occupied or at war with the Chinese, the Japanese, the French, the Americans and the Cambodians. The country successfully resisted all these invaders and, against all odds, succeeded in defeating two of the world’s greatest military powers – the French and the Americans – notwithstanding them using their most sophisticated weapons against “these peasants”, as an irate American politician noted in the 1960’s. As for the Chinese and Soviets who liked to tell their “little brothers” what to do, they were politely, but firmly told to mind their own business.

From 1940 till 1990, foreign influence was not just all-pervasive, it was also rapidly changing. As one guide told us: “In my lifetime, we already had to learn five ‘second’ languages. When I was born, at school we were taught French, in addition to Vietnamese. From 1940 till 1945, we had to drop French and learn Japanese. Then we went back to French. From 1954 till the late 1960’s, we learnt Chinese. Then, until 1990, when our leadership sided with the Soviets, we had to learn Russian. From then onwards until today, we are taught English. What will we learn next?”

Today, Vietnam’s people embrace foreign visitors with a warmth, openness and kindness that you find in few other countries. Wherever you go, the Vietnamese are eager to engage with you. In the rural areas, everyone invites you to their homes. They are not asking for favours or for money. They appear genuinely happy to see you and to share with you what they have.

How do the Vietnamese feel today about the wars, especially “the American war” in the 1960’s, as they call it? Wars are not on anyone’s radar screens here. Everyone is trying to get on with their lives as best they can. The people from what used to be South Vietnam will tell you that “we are all Vietnamese now” and they look sincere when they say it. How do they feel about Americans visiting the country today? They are most welcome!

The energy and chaos of Vietnamese streets

Vietnam’s street culture is one of the most vibrant, dynamic, and immersive in the world. Unlike in many Western countries where life happens indoors, in Vietnam, the streets are an extension of daily life—places where people eat, work, socialize, and even nap. This makes Vietnamese cities feel incredibly alive, energetic, and full of character.

Tiny plastic stools and low tables are a signature of Vietnamese street food. Locals sit, chat, and enjoy fresh meals in the open air. Many sellers operate from bicycles or carts, offering everything from Bánh Mì (baguette sandwiches) to fresh sugarcane juice.

The people here do appear much busier than the relaxed Thais, and they are a lot louder than them (travelling on a plane full of Vietnamese, as we have done, requires earplugs).

This is reflected in the economy, which posts a consistent and enviable growth rate of more than 6% per year, among the top performers globally (which, in recent years, is higher than in China).

Social contradictions

The rate of growth and the uneven distribution of wealth has created a problem of its own, which is perceptible by those who feel that the government has allowed some to get very rich and the vast majority to remain in poverty. But overall, the Vietnamese seem happy with their lot and especially grateful that the wars are over and that the country is now friends with all nations.

The country’s contradictions are in plain sight: it’s impossible to walk even a few hundred meters in Saigon without seeing posters celebrating the triumph of communism in Vietnam.

Everywhere you look, there are images and slogans celebrating Ho Chi Minh, the founder of the nation and the person in whose honour Saigon was renamed (although the locals continue to call it “Saigon” – it’s shorter and easier to pronounce, they will tell you).

“Capitalism is a leech that sucks the blood of the working people”, was one of Ho Chi Minh’s favourite sayings. What, we wondered, would the great leader think of his nation if he were alive today?

Ironically, in the centre of Saigon, his statue is surrounded by dozens of shops selling ultra-luxury brands manufactured by precisely those “imperialist” countries he fought for 30 years to get rid of, a conflict in which nearly a third of the nation’s population either lost its life or was displaced. Not to speak of the outlandish hotels situated only a few steps from his statue, and the extravagant cars surrounding them.

Of course all these luxuries are only available to a minuscule part of the population, the rest live in conditions that are often indescribable.

But for Mrs. Đẵớ, born in the 1940’s, with whom we spent an afternoon in Hoi An, life is now good, at least in comparison to what it was before: “My first 50 years were about survival – how to have enough food and how to manage our orchard, when almost every day someone was killed during the constant wars we had.”

“Now I’m very well”, she added. “For the last 20 years or so, we’ve had enough to eat and no one gets killed”, echoing how most people in Vietnam feel, who often complain about the corruption in the country, but are nevertheless grateful to the Communist Party for the peace and relative well-being they now enjoy.

Vietnamese cuisine

Because of all the foreign influences and its geographic location at the crossroads of some of the world’s most important trading routes, Vietnamese culture blends indigenous traditions with Chinese Confucian values, Buddhist spirituality, and French colonial aesthetics.

Nowhere is this better reflected than in its fabulous food.

Vietnamese cuisine stands out in Southeast Asia for its light, fresh, and balanced flavours, emphasising fresh herbs, vegetables, and light broths rather than heavy curries or thick sauces, as you would find for example in Thailand.

The Taoist philosophy of âm dương (yin-yang balance) plays a big role, ensuring that many dishes offer a balance of hot & cold, salty & sweet, sour & spicy flavours. Unlike Thai or Malaysian food, Vietnamese cuisine uses very little coconut milk or dairy. Dishes are often grilled, boiled, or stir-fried rather than deep-fried.

Instead of relying heavily on strong spices, Vietnamese food gets its depth from fish sauce (nước mắm), shrimp paste, fermented sauces, lime, and fresh herbs. Spiciness is much milder compared to Thai or Lao food and is often added individually rather than being cooked into the dish.

Rice is the foundation of every meal, whether as steamed rice (cơm), sticky rice (xôi), or in noodle form (bún, phở, miến). But unlike Thailand, where jasmine rice dominates, Vietnamese rice dishes often feature fragrant broken rice (cơm tấm) or short-grain varieties.

Fresh basil, mint, coriander, perilla, and sawtooth herb are always served with food, often wrapped in lettuce or rice paper. This is different from Thai and Indonesian cuisine, where herbs are more commonly cooked into dishes rather than eaten raw.

Unique to Vietnam, the French introduced baguettes, pâté, and coffee, leading to dishes like Bánh Mì(Vietnamese sandwich) and Cà Phê Sữa Đá (Vietnamese iced coffee). While the Philippines and Malaysia also have colonial influences, Vietnam’s fusion with French flavors is more distinct.

Because many times in the past food was scarce, the Vietnamese learnt to become inventive, to cook with bones, rather than meat. This is best exemplified in the all-pervasive Phở (an aromatic beef or chicken noodle soup with vegetables, which the Vietnamese eat all day long). Phở (pronounced as in French “feu”) is sold at every street corner. We ate it almost every day for breakfast and said to ourselves that if we continued like this, we would surely live to 120!

When asked about food, the Vietnamese will tell you that it is conceived for people on the go – light, nourishing and rapidly digested, it’s ideal for those coming and going from their work in the fields. But this is only half the truth – Vietnamese food is also conceived to maximise social encounters. Easily and effortlessly prepared, it allows people to visit each other frequently, a main characteristic of Vietnamese culture, where people are constantly meeting each other in their homes or on the street.

Due to war, economic hardship, and rapid urbanization, many people couldn’t afford to dine in restaurants. This led to a thriving street food culture, where small vendors serve quick, affordable, and flavorful meals. As an example, Bánh mì emerged as a fusion of French and Vietnamese traditions, using cheap baguettes filled with local ingredients.

The Chinese approach to food, on the other hand, is often frowned upon. As one of our guides told us: “In China, much of the food is presented as a show. It focuses on decoration and colour, which is why you see a variety of colours in their dishes. In contrast, Vietnamese food is simpler, with fewer colors. The colours in Vietnamese cuisine are primarily white for rice and green for vegetables”. He added: “If a beautiful lady wears too much makeup, it can detract from her natural beauty. We apply this philosophy to our culinary practices”.

Show-off Sundays

On Sunday afternoons, the Vietnamese (especially young girls) love to dress up and stroll around parks and avenues, often accompanies by photographers.

What do they do with these photos? Oh, we were told, it’s a way for young women to feel good about themselves, to record their beauty and, who knows, to entice potential suitors. There is no problem in photographing them – all you have to say is: “You look so beautiful, may I take a photo of you?” to have them stand in line to be photographed.

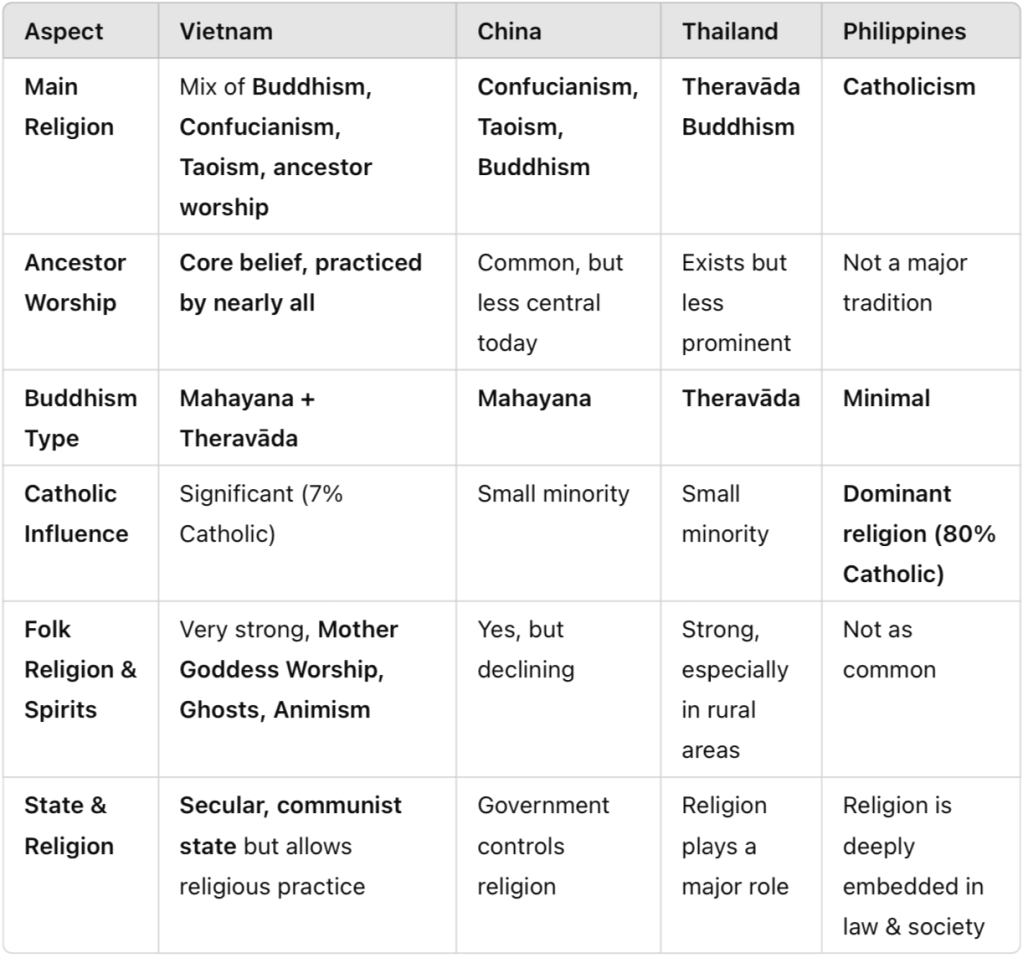

Spiritual and religious life: as unique as Vietnam’s food.

Even though Vietnam is officially a secular state, spirituality is woven into every aspect of daily life, from ancestor altars in homes to the smell of incense in street-side shrines.

Unlike countries with a single dominant religion, like Thailand or Cambodia, Vietnamese spirituality is fluid, adaptable, and deeply personal. It reflects a philosophy of balance, respect for the past, and connection to the unseen world, making it one of the most fascinating religious landscapes in the world.

Vietnamese spirituality is a uniquely rich blend of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, indigenous beliefs, ancestor worship, and Catholicism.

Buddhism (Vietnam’s most common religion)

Vietnamese Buddhism is primarily Mahayana (like in China and Korea), but Theravāda Buddhism is also practiced, especially in the Khmer communities of the Mekong Delta. Compassion (từ bi) and karma (nghiệp) are central concepts in Vietnam’s daily life, and monks and pagodas (chùa) play a major role in the country’s spiritual life.

During our time in Hué, Vietnam’s ancient imperial capital, we paid a visit to the 400-year-old Khanh Long Pagoda, where we were received with songs and a Mahayana ceremony by the nuns. This was followed by an in-depth description of each statue (a giant one of the historical Buddha, surrounded as in common in the Mahayana tradition by two Bodhisattvas, one helping those who after death are reincarnated in hell, the other one helping forlorn sailors). This was followed by an extraordinary vegetarian lunch. Accustomed to the rigidity of the Thai monks (and the fact that nuns are practically not present in the religious hierarchy) we were pleasantly surprised by how open and giggly the two nuns were. As elsewhere in Vietnamese society, they were also remarkably “tactile” (in Thailand touching or being touched by a member of the religious community is a definite “no no”).

Confucianism (moral and social philosophy)

Confucianism is not a religion but a social and ethical system that has deeply influenced Vietnam since Chinese rule. You sense it strongly in Vietnamese society, through a deep respect for parents and elders, in education, where scholarship and meritocracy are core beliefs, and through family and societal roles, which are clearly defined and tend towards harmony and duty. The aspect of duty, greatly helped the Vietnamese to win wars through extraordinary battlefield discipline.

Oranges and mangos are common offerings ,symbolising wealth, good luck, and spiritual devotion.

Taoism (harmony with nature and spirits)

Taoist ideas are deeply embedded in Vietnamese life. Most Vietnamese believe in a strong balance between nature and life (they will tell you that their food is much better than the Chinese because it is “closer to nature”). Feng shui, a core Taoist belief, determines how houses and tombs are built.

We saw this very clearly during our visit to the home of Phan Thuan Thao, a descendant of Emperor Dong Khanh. The altars of her ancestors are placed facing a beautiful garden, behind which is water, in accordance with Taoist feng shui rules: “There used to be a river here, but now we still have a pond, which is essential to the well-being of our ancestors’ soul”, explained the Thao. The centrepiece of the beautifully arranged garden is a rock, which in Taoist belief best showcases the effect of the passage of time. But if you look closely, there are also smaller, effigies and statues representing the different areas of Vietnam. This indicates that the Thao’s great grandfather was an important man, who had an influence over all of the country (indeed, born in the countryside and from humble origins, he had reached the position of Mandarin in the Imperial Court through Vietnam’s meritocratic system, similar to Imperial China’s system).

The visit to Phan Thuan Thao’s garden and home was followed by an extraordinary lunch in six courses, which was presented step by step, in line with Imperial procedure (normally the Vietnamese, as the Thais, place all dishes on the table at the same time). Some of the dishes were also elaborately decorated and included carved vegetables, also common in royal households.

It is common in Taoist temples to encounter deified statues of past kings or generals. These are honoured for their virtues and prayed to, in the hope that they will support personal endeavours.

Ancestor worship (core Vietnamese spiritual practice).

Not just Princess Ngoc Son, but any Vietnamese family that has room for it, will have an ancestral altar at home. This is tied into the the belief that deceased family members continue to influence the living.

Offerings of food, incense, and “spirit money” are given on special days. Joss paper, including paper replicas of material goods such as houses, cars, clothing, smartphones, gold bars, and even credit cards are burned, for use in the afterlife. The belief is that by burning these offerings, the spirits of ancestors receive them in the spiritual realm and protect present-day family members.

Indigenous folk beliefs and animism

Many Vietnamese believe in spirits, ghosts, and supernatural forces. Shrines to local deities and nature spirits can be found in forests, rivers, and even street corners.

Thần Tài – Ông Địa altars are found in many businesses. They are best understood as a syncretic blend of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism. The shrine serves to honour Thần Tài (God of Wealth, seen here on the right), usually depicted as a bearded man holding gold or a treasure, and wearing an official’s hat, and Ông Địa (God of the Land, seen here on the left) – often shown as a smiling, chubby man with a bare belly, holding a fan or a gold ingot. This altar is believed to bring protection, prosperity and good luck in business ventures.

Đạo Mẫu is a syncretic Vietnamese belief system centered on mother goddesses, and which blends shamanism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and local spirit worship. Lên đồng spirit possession rituals are colorful and central to this tradition, involving music, dance, and changes of elaborate costumes. Their temples are beautiful!

Catholicism

Unusually for Southeast Asia, Vietnam has a large Catholic population, which was introduced by Portuguese and later French missionaries, starting in the XVIth century. Some of the sanctuaries, such as Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon (built by the French) is truly impressive in size.

Cao Đài (a unique Vietnamese religion)

Founded in 1926, Cao Đài is an indigenous Vietnamese religion that blends Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam. It recognizes Jesus, Buddha, Confucius, and Victor Hugo (yes, the French writer) as spiritual guides.

We were very impressed by the clarity of message of the Cao Đài temple we visited in Saigon, and the warmth with which we were received.

Spirituality in everyday life

In addition to the above, even among non-religious people, spirituality is deeply embedded in Vietnamese customs, daily practices, and social interactions, for example by avoiding certain numbers (the number 4 is considered unlucky, since tứ sounds like “death”), while 8 is lucky. For weddings, business and picking a baby’s name, fortune-telling and astrology are absolute “musts” for most Vietnamese.

Diverse ethnic groups.

Vietnam is a multiethnic country with 54 officially recognised ethnic groups, each with its own unique language, culture, and traditions. While 85% of the population is ethnic Vietnamese (Kinh), the other 53 groups play an essential role in the country’s cultural richness.

We met members of the Thái, H’mong and Nùng communities. We felt that they were well integrated and in no way discriminated against. In large part this has to do with the fact that they all supported the war effort in the 1960’s and 1970’s, for which not just the government, but the Kinh majority have always been grateful.

A beautifully diverse countryside, with breathtaking landscapes and wonderful, picturesque scenes.

As you would imagine from a country which is so vast, the landscapes of Vietnam are very diverse. A lot of the nation’s beauty has been eroded by “progress” in the form of electrical cables and concrete wherever you look. Nevertheless a lot remains and is a joy to see!

Motorcycles

There are almost as many motorcycles as people in Vietnam – 72 million registered as of 2023, representing one of the highest rates of ownership in the world.

Motorcycles aren’t just a means of transport in Vietnam, they are way of life – they are used to carry entire families, for moving furniture or livestock, and even for siestas.

The density of motorcycles makes it challenging to cross streets – the only way to cross is just to venture out…and hope for the best!

Roosters

Everywhere we have travelled, we have seen roosters, but there is no country we have been to where they are as beautiful as in Vietnam!

Hotels

We stayed in 7 hotels during our four weeks in Vietnam and nearly all of them surprised us with their extraordinary quality and service. Most of them have been built recently and are on a par with the best in the world.

The biggest highlight: Vietnam’s people

Would we return to Vietnam? Yes, we would. There is a lot more to see and to experience in this vast country. But what would really make us come back are not the sights, it’s the warmth and kindness of the people. They are a tribute to resilience and a living example of the Vietnamese concept of hòa hợp (harmony) which so deeply influences social interactions, and which made us feel so incredibly warm and welcome in this beautiful country.

Thank you. Will read and look at pics with pleasure. You guys are the Balzac of travel reports !

LikeLike