If Beijing is the political and historical heart of China, Shanghai is the modern, powerful, hyper-energetic, and trend-setting economic and cultural capital. No other city in Asia comes close to offering the vibrancy of Shanghai.

But it wasn’t always this way. Before the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, Shanghai was a well-to-do, but unimportant regional centre, of which there were many in China at the time. Unlike Beijing (the capital in Imperial times) or Nanjing (a former capital, before Beijing), Shanghai was only a county seat under the jurisdiction of the much larger Songjiang Prefecture. Its status was relatively low in the imperial hierarchy. Its wealth derived entirely from domestic trade along the Yangtze River, since the powerful Qing court restricted nearly all foreign trade to the port of Canton (Guangzhou) in the south.

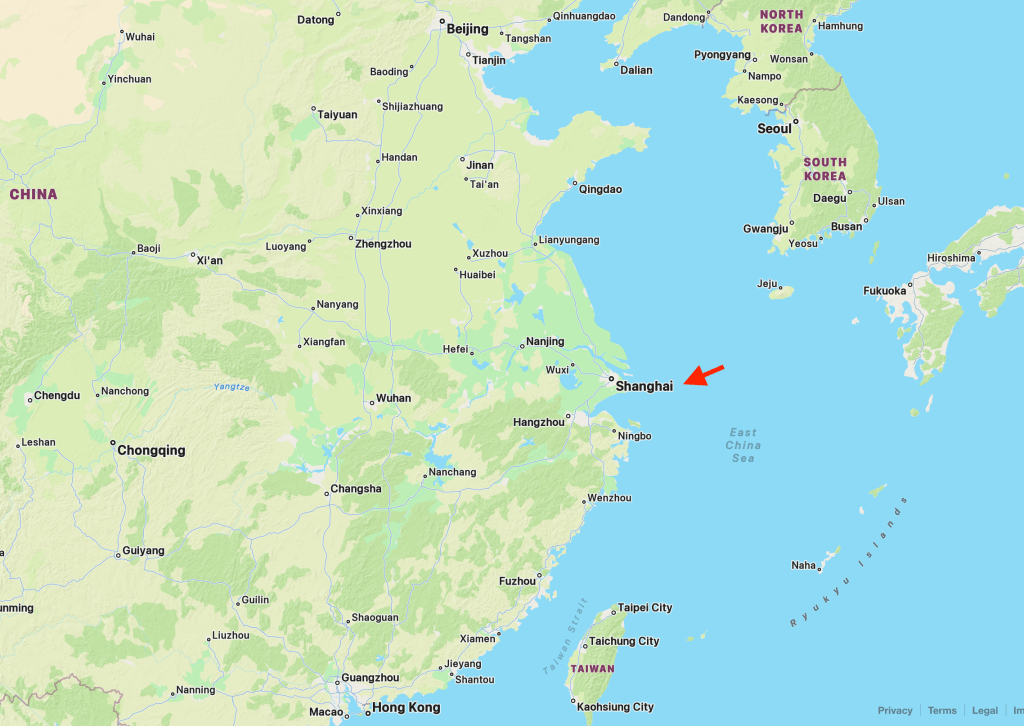

The presence of the Huangpu River, a major tributary flowing into the Yangtze, was Shanghai’s greatest natural asset. It provided deep-water access for large ships and a strategic inland position that Canton lacked. It was this strategic geography, combined with its existing infrastructure for internal commerce, that made Shanghai instantly appealing to Western powers looking for a new, more efficient point of access to the vast Chinese interior after the first Opium war ended in 1842 and opened China to increased trade.

The Treaty of Nanjing, which concluded the first Opium war in 1842, forced the Qing Dynasty to open five major ports, including Shanghai, to British trade and residence. This event irrevocably shifted Shanghai’s focus towards internal commerce and, over time, to international finance.

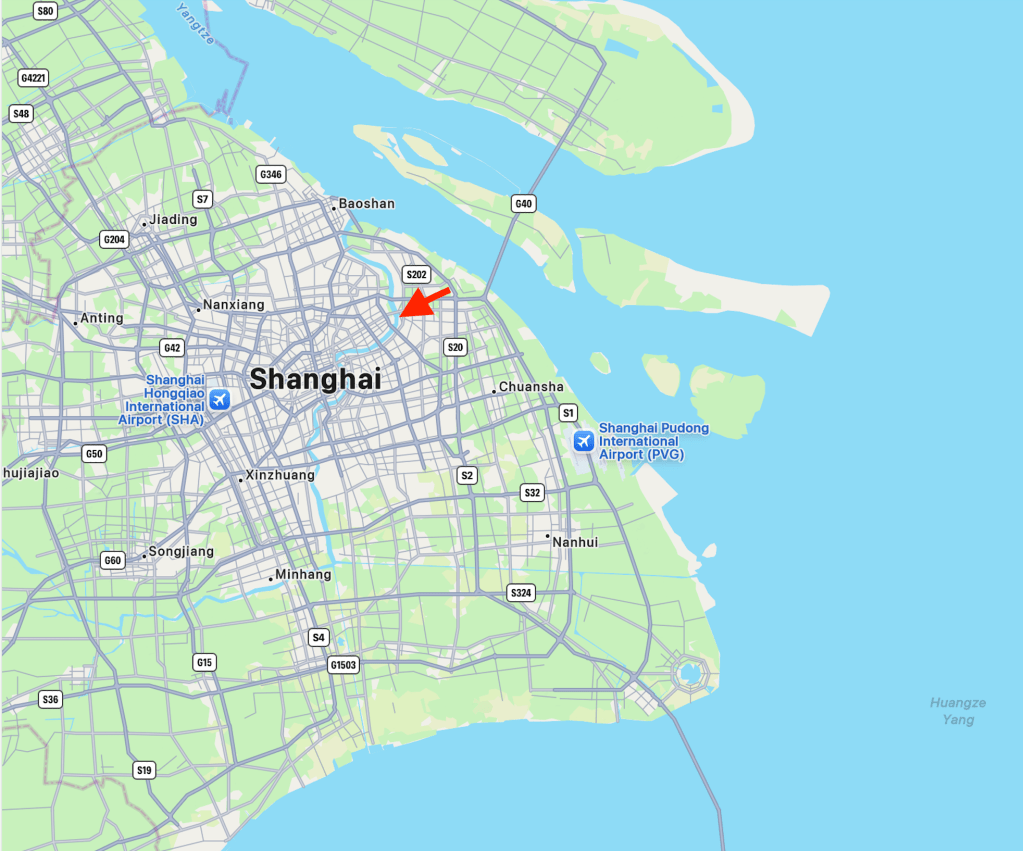

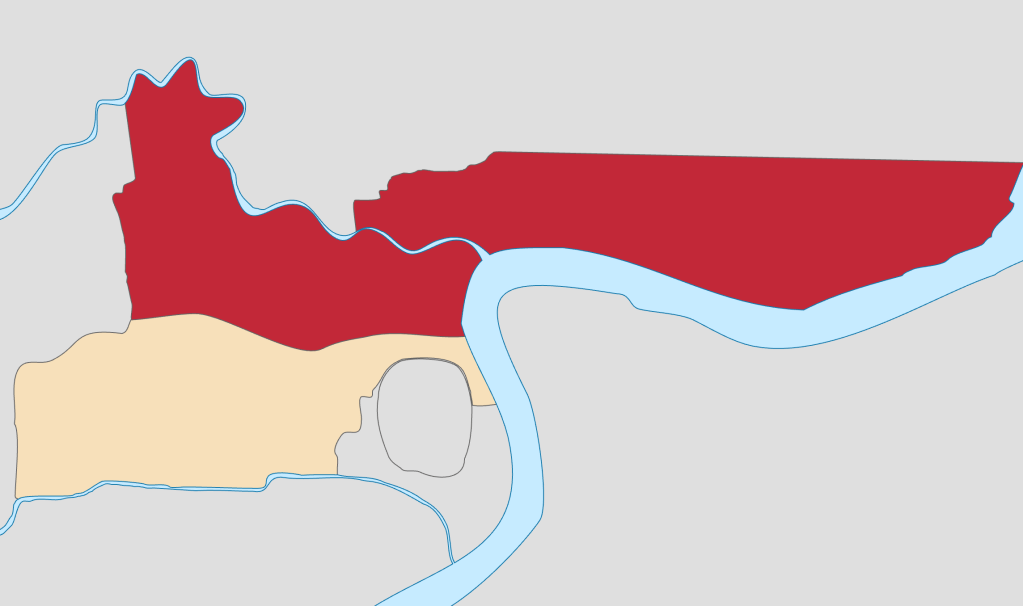

The foreign powers didn’t occupy the old walled Chinese city; instead, they were granted land for settlements just to the north. These settlements, known as “concessions”, were not colonies but leased territories where foreigners enjoyed extraterritoriality – meaning they were governed by their own laws, not Chinese law. This created a city-within-a-city structure with three main political zones:

- The International Concession: formed by the merger of the British and American concessions, and governed by the Shanghai Municipal Council, it became the primary hub for global finance, banking, and big business.

- The French Concession: administered by the French Consul, this area developed into a highly desirable residential district characterised by European-style villas, tree-lined avenues, and distinct art déco architecture.

- The old Chinese city: the original walled settlement, which remained under Chinese administration but was increasingly surrounded by the wealth and influence of the foreign enclaves.

Creating the “New York” DNA

This unique political fragmentation is the major reason why Shanghai earned the nickname “Asia’s New York.” It fostered:

- Unfettered capitalism: The international and French concessions created an environment where international trade and finance could operate almost entirely outside of Chinese imperial regulations. They became a free port – a hub of laissez-faire capitalism that attracted merchants, financiers, and speculators from around the globe. Shanghai’s concessions were run by business people, with no governmental oversight, resulting in a pragmatic environment, where it was all about business and free enterprise (in a larger sense, including freedom of speech and ideas, which is the reason why China’s Communist Party was founded in the French Concession in 1921).

- Cultural fusion: The blending of English commercial architecture, French residential planning, and Chinese populations created a very original cosmopolitan culture – a mix that fostered unique Shanghainese customs, fashion, and cuisine known as Haipai (Shanghai Style).

- The “Paris of the East”: In the 1920s and 30s, Shanghai exploded into a flamboyant, decadent, and dynamic world city, often referred to as the “Paris of the East.” It was a center of jazz, film, theatre, organized crime, and global refuge (it famously took in thousands of Jewish refugees during WWII).

This era established Shanghai not just as a trading port, but as China’s undisputed capital of modernity, commerce, and international intrigue.

Baghdadis in Shanghai

The Sassoon and Kadoorie families, two Jewish families from Baghdad, played a key role in transforming Shanghai into the “New York of the East” through massive investments in finance, real estate, and iconic architecture.

The Sassoons, led by Sir Victor Sassoon, were instrumental in shaping the city’s famous skyline, especially along the Bund. Their most recognizable legacy is the Cathay Hotel (now the Fairmont Peace Hotel), which was Shanghai’s first skyscraper and an Art Deco icon when it opened in 1929. They also built other major properties, including the Cathay Mansions and the Grosvenor House (now part of the Jinjiang Hotel).

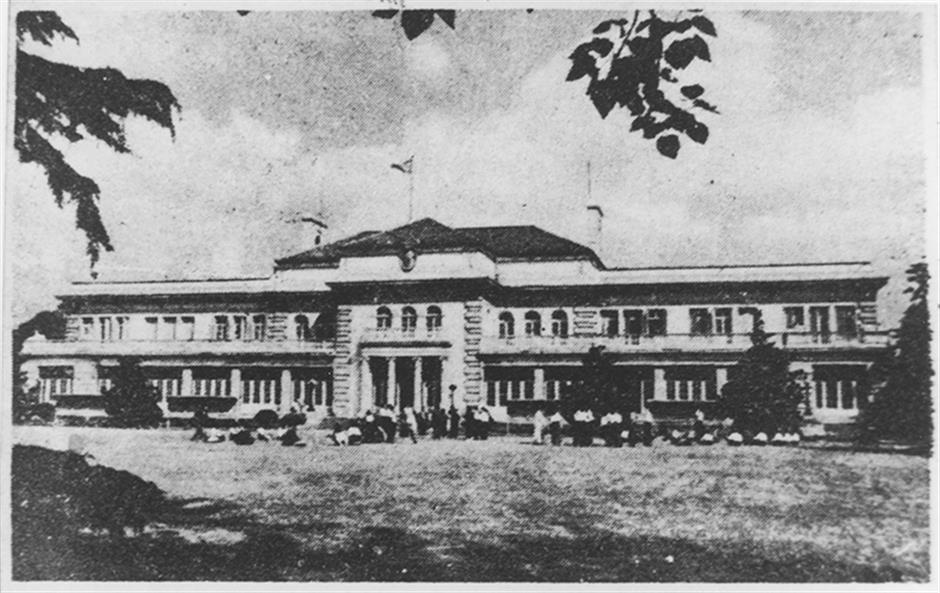

The Kadoories also left a mark on the city’s architecture. They owned and developed the magnificent Marble Hall (now the China Welfare Institute Children’s Palace) and were involved in the ownership and development of major hotels like the Majestic Hotel and the Astor House Hotel.

The families, especially the Sassoons in the earlier years, initially built their wealth through the opium trade (which was legal in British-controlled India but illegal in China), eventually diversifying into banking and finance. David Sassoon, the patriarch, was a co-founder of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (now HSBC) in 1864, demonstrating their early and deep involvement in the region’s financial institutions.

Both families introduced and pioneered modern business practices in China, including innovative financing, credit arrangements, and standardised accounting and communication systems, helping to establish Shanghai as a major financial market.

The families’ grand hotels and lavish parties, notably Victor Sassoon’s at the Cathay Hotel, made Shanghai synonymous with luxury, glamour, and a vibrant, “roaring twenties” nightlife, attracting international businesses, celebrities, and capital. This cosmopolitan atmosphere was central to its image as the “Paris of the Orient” and the “New York of the East.”

Shanghai’s “golden era” ended with the Japanese occupation (1937–1945) and was formally halted by the end of the concessions in 1943. After the Communist takeover in 1949, Shanghai’s international flavour was largely suppressed; its resources were redirected to supporting Chinese national industry, and its role as a global finance centre lay dormant for decades.

The arrival of communism meant that the Sassoons lost most of their assets in Shanghai, as well as their standing as one of the wealthiest families worldwide in the 1930’s. The Kadoories also suffered, but less. They were able to divert some of their investments to Hong Kong in the late 1940’s and rebounded during the Deng Xiaoping era (see below).

The modern era: Deng Xiaoping and Pudong

The comparison to New York City was revived and cemented only after 1990, when the central government, under Deng Xiaoping, designated the vast, undeveloped Pudong area, the swampy land across the Huangpu River from the old Bund, which had been the centre of the international concession, as a special economic zone.

This decision led to Shanghai’s second major transformation, directly leading to the city we see today:

- The Second Financial Hub: Pudong was designed from scratch to be the modern financial heart of China. It was an ambitious, state-backed project to create a global business district rivaling Manhattan’s scale and ambition.

- The Skyline Race: The ensuing construction boom—which saw the creation of the Oriental Pearl Tower, the Jin Mao Tower, the Shanghai World Financial Center, and the Shanghai Tower, created one of the most futuristic, recognizable, and fastest-developing skylines on the planet. This modern, architectural ambition is the visual proof that Shanghai has inherited the title of “Asia’s New York.”

As Shanghai started to re-emerge as China’s financial capital in the 1990s, Lawrence Kadoorie, the family patriarch at the time, was one of the first foreign businessmen to meet with Deng Xiaoping. This meeting in the early 1980’s was a symbol of China’s new opening to foreign capital and a major diplomatic coup for the family. Subsequently, the Kadoories made direct investments, particularly through their luxury hotel group, leading the family to develop a new Peninsula Hotel in the heart of the city, on the historic Bund. While the hotel opened only in 2009, the groundwork and renewed interest in the city’s premier real estate were rooted in the confidence instilled during the Deng era’s push for economic liberalisation and set the tone in the early 1980’s for the city’s subsequent booming renaissance.

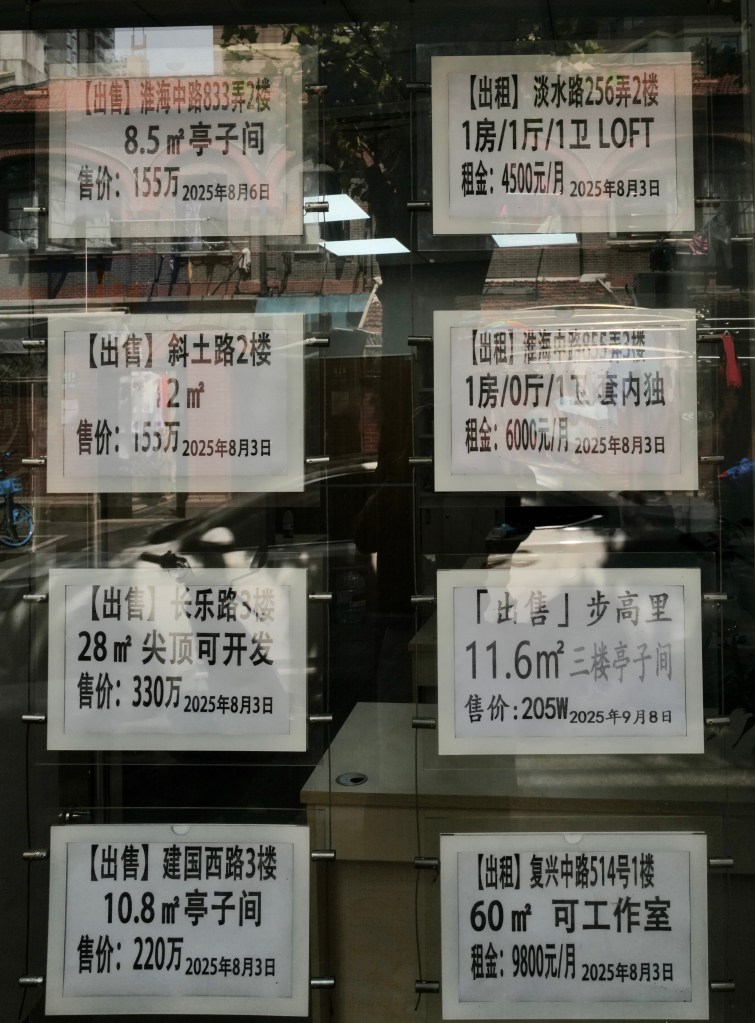

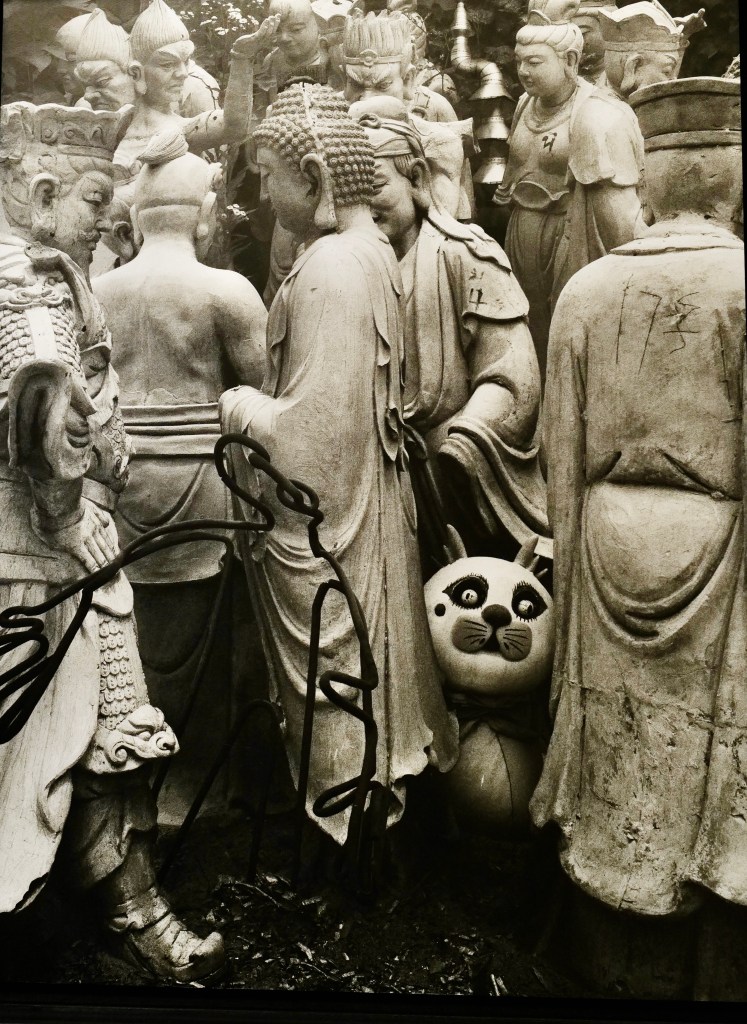

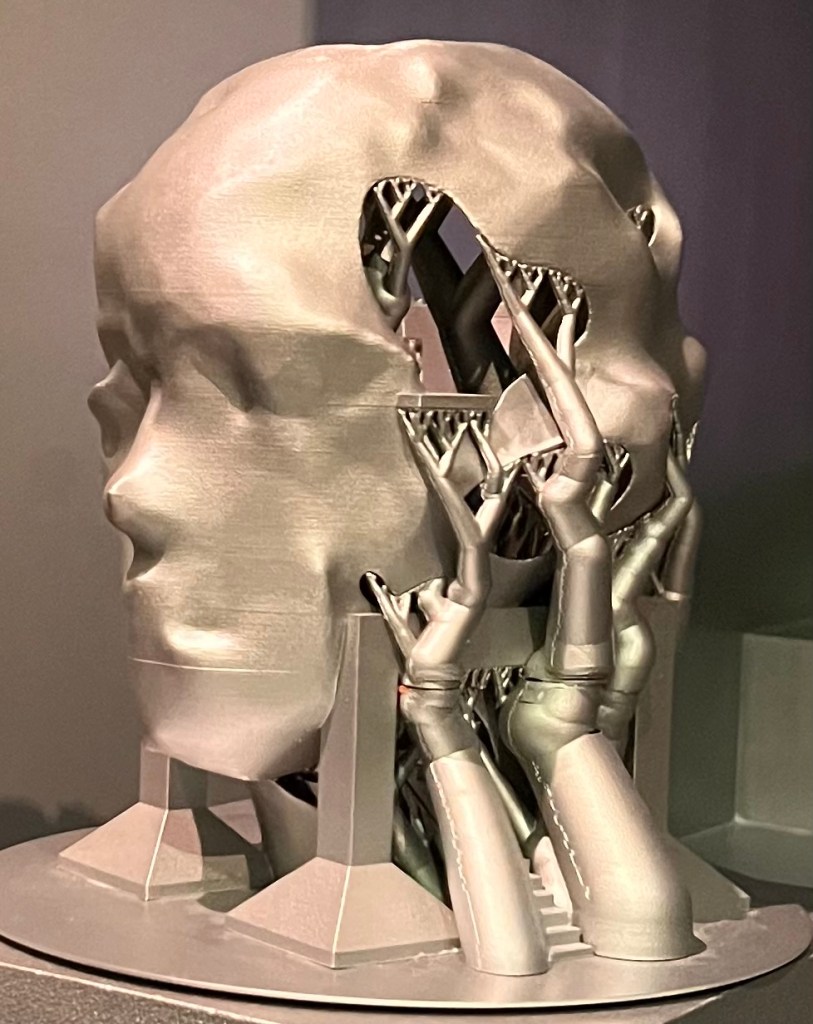

We had the pleasure of visiting Shanghai over 5 days in September 2025, and loved every minute of it. The lights, the vibrant atmosphere, the beautiful buildings (very well restored), the great hotels, the amazing food (there are 51 Michelin starred restaurants in Shanghai), the great art, the super modern museums and, especially, the friendly and welcoming people, made us want to stay a lot longer. We’ll be back, for sure!

Finally I am up to date with your reviews. I do not remember if in my previous comments I emphasised the fact you do not only provide a travel report but all of them begin by avery interesting and useful historical perspective. I appreciate this introduction which very often allows to understand why a country, a town or people from the area are what they are. Continue to let us dream.

LikeLike