Australia is a truly unique travel destination, the only country that is also an entire continent (often called the “island continent”). This results in a staggering diversity of landscapes, climates, and life, and a history of human occupation, that is found nowhere else on Earth.

We spent five weeks visiting only a small portion of Australia, essentially the southeast corner. It was enough to get a glimpse of this vast island, to understand its origins and, especially, to whet our appetite for more. We are leaving the north and west for a subsequent trip.

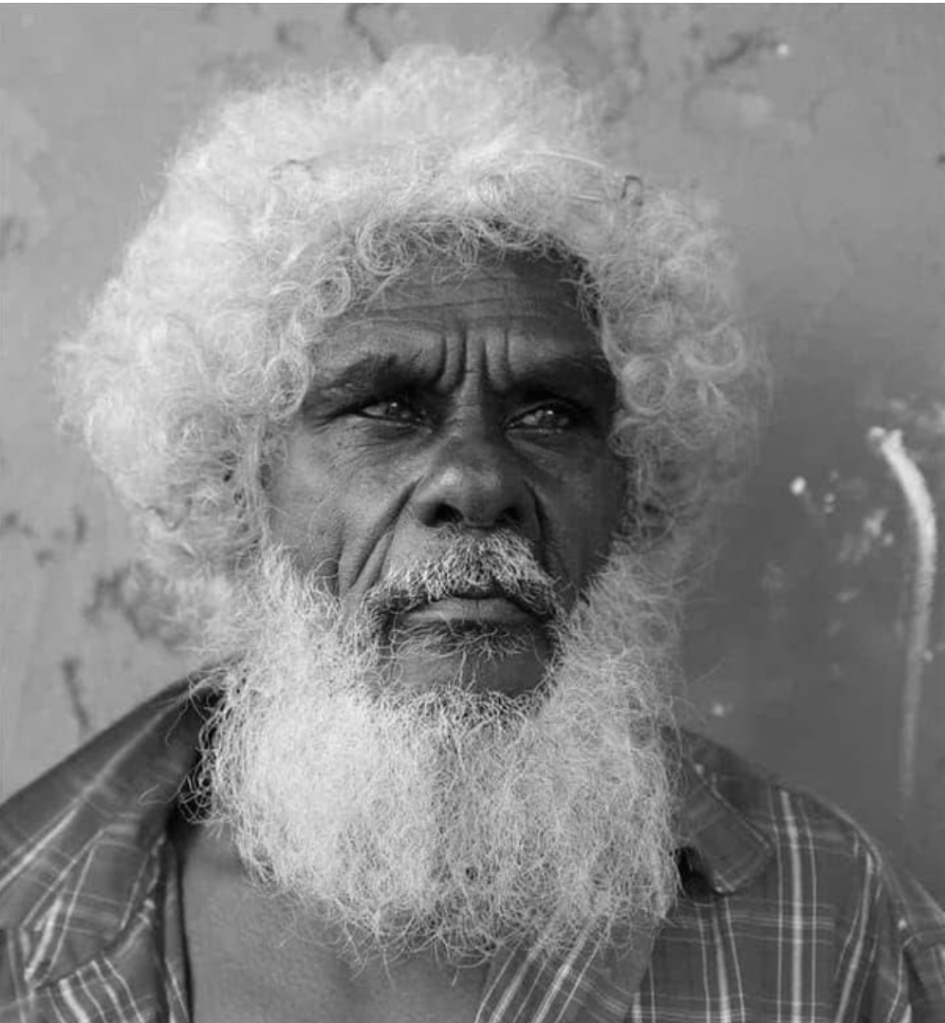

Beyond the landscapes and modern-day Australia, what captivated us from the start is the Aboriginal settlement of this part of the world.

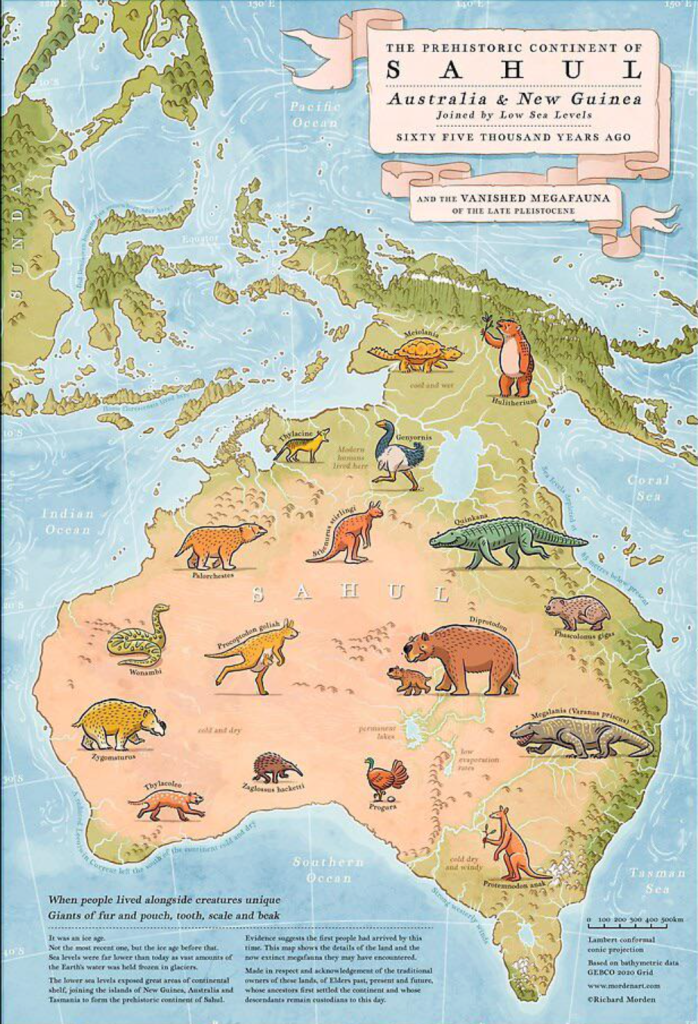

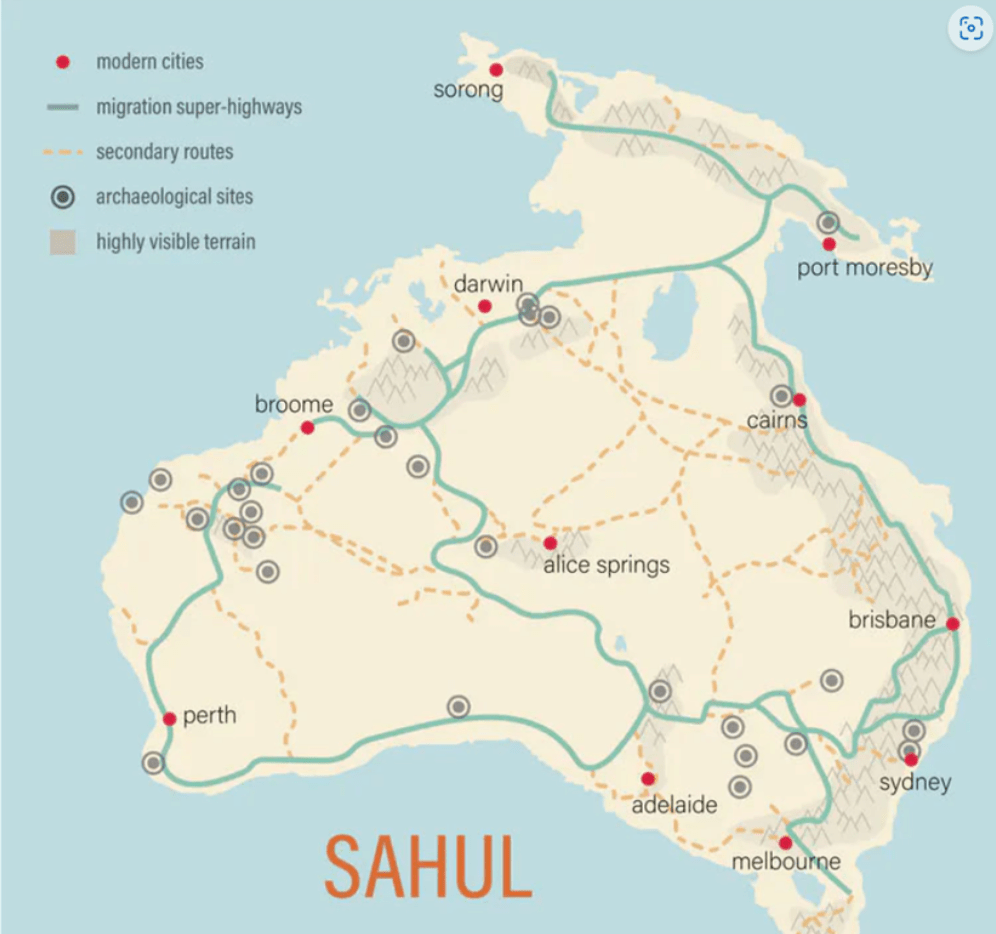

Archaeological and genomic evidence indicates that the ancestors of today’s Aboriginal Australians arrived what was at the time the supercontinent Sahul (which included New Guinea), about 65,000 years ago.

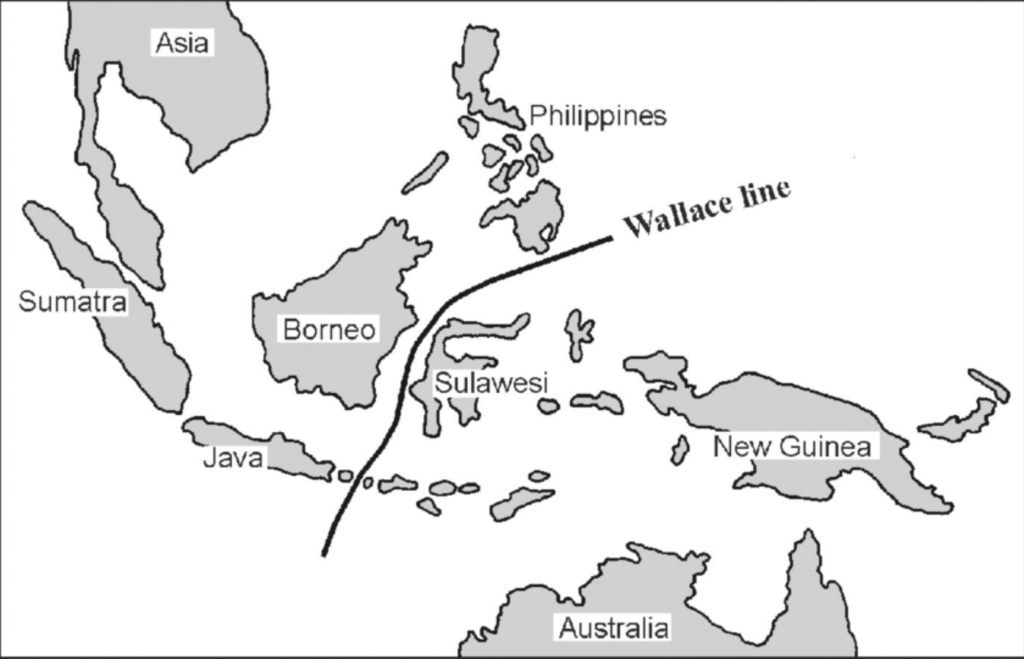

This migration was part of the initial “out of Africa” dispersal of modern humans. Even with lower sea levels at the time, the journey required sophisticated seafaring skills to cross several sea gaps, most notably the Wallace Line.

The Wallace line is a natural boundary which created a lasting barrier, separating animal species for many millions of years. Even though islands such as Bali and Lombok (nowadays both part of Indonesia), are separated by only 35 km by sea, no large animals were able to cross. The Lombok Strait is deep enough, so that it never became dry land. It remained an open ocean channel, preventing terrestrial animals from walking across, even at the lowest sea levels, making it a permanent biological barrier for over 50 million years.

This means that animals in the areas east of the Wallace line developed in complete isolation from the rest of the world, leading over many millions of years to a radically different fauna.

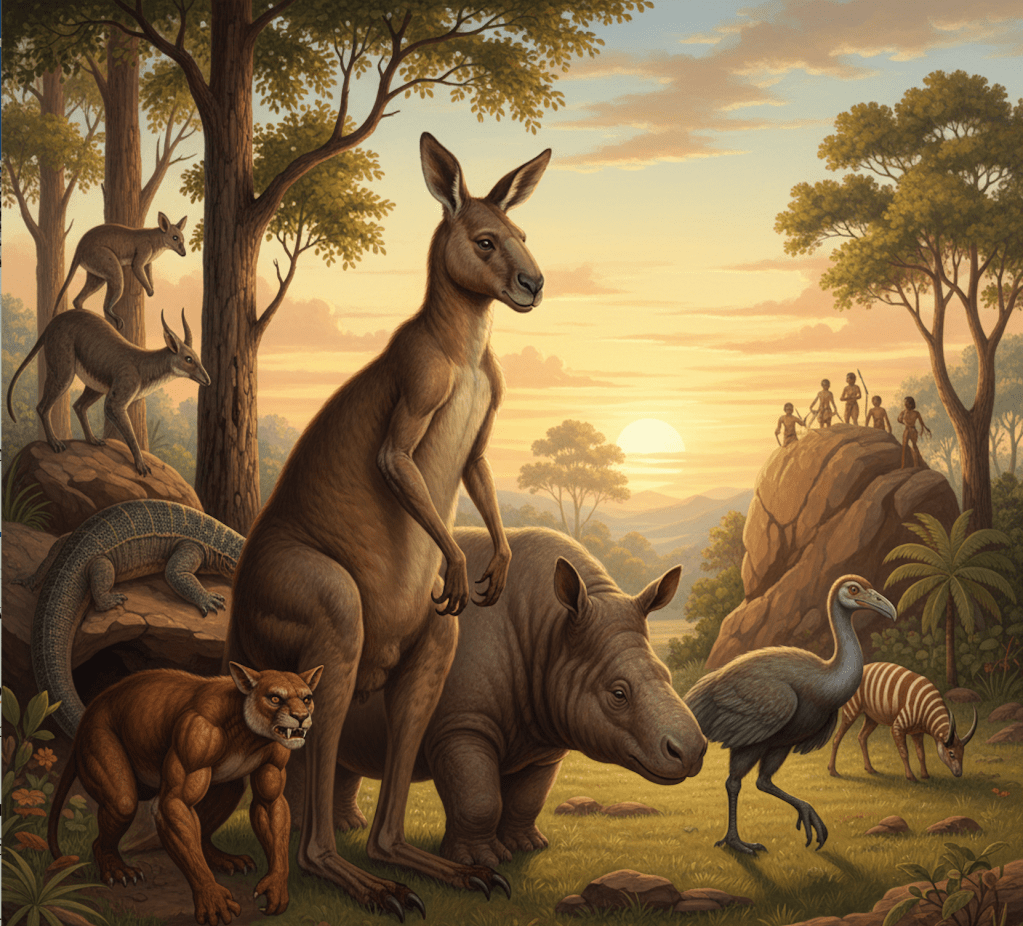

On the western side of the Wallace line, large placental animals such as tigers, elephants, rhinoceros and large apes such as orang-utans, were the dominant species, all of which are still with us today. To the east, on Lombok, New Guinea, and Australia, the large animals were completely different. They included:

- Giant short-faced kangaroo : A massive, robust kangaroo with a short face and forward-facing eyes, standing much taller than modern kangaroos.

- Diprotodon optatum: The largest marsupial ever, resembling a giant wombat or rhinoceros, a herbivore that roamed the plains.

- Marsupial Lion: A formidable, cat-like predator with powerful jaws and a unique killing bite.

- Demon Duck of Doom: A massive, flightless bird, much larger than an emu.

- Giant Goanna: A huge monitor lizard, one of the largest terrestrial lizards ever, a top predator.

The animals you casually encounter today in Australia are and different to what we have seen in other parts of the world, take a look at the ones below.

Human settlement of Australia

The first humans to successfully cross the Wallace Line and who reached what is now Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania, did so around 65,000 years ago. They were anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens), who had left Africa 10’000 years before. A recent genetic study has found that today’s Aborigines are direct descendants of these first people, confirming that they represent the oldest continuous human culture on the planet.

The overwhelming consensus among researchers is that the migration to what is now Australia was deliberate and not an accident. What these early migrants accomplished, no other large animal species (and no other hominid such as Homo erectus and Denisovans) achieved, before or after. Their resilience and capacity to adapt was simply unique in the history of humanity.

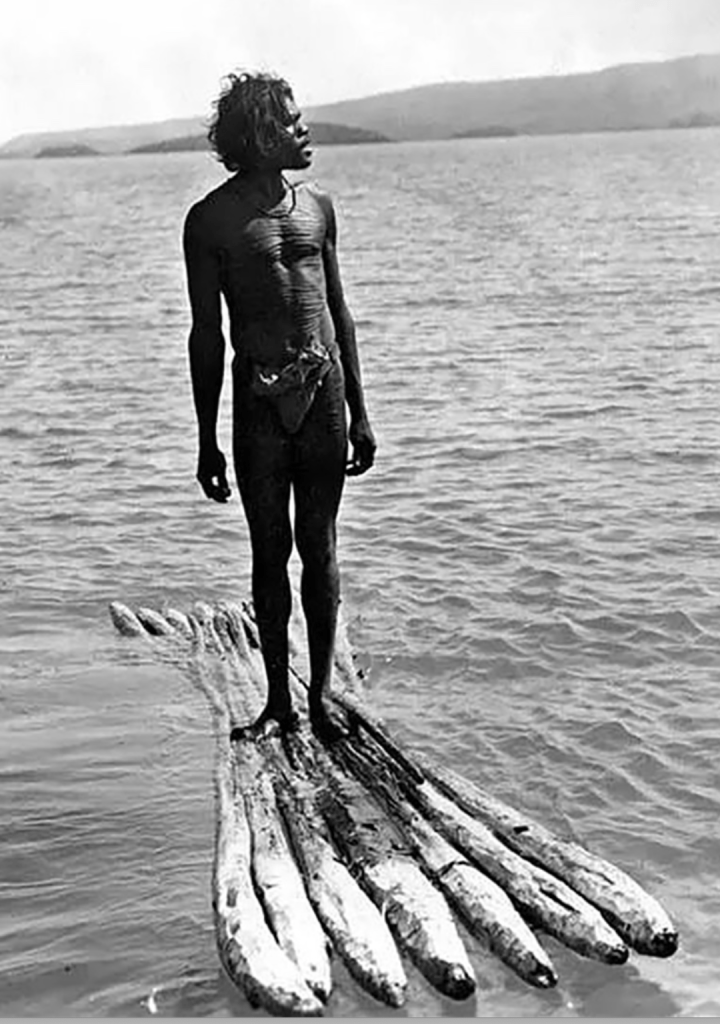

It was, for the time, an amazing undertaking. It required multiple sea crossings, including at least one open-ocean voyage of 70 to 100 kilometers, with no land in sight, and necessitating a deep understanding of stars, currents, winds, and other natural signs to maintain a course over open water. These migrants would have needed to build, maintain, and successfully operate seaworthy vessels – probably boats made out of bamboos and fitted with a paddles or even sails made from woven materials, which could be propelled and steered against the strong currents.

Beyond sophisticated technology, these people who lived over 65’000 years ago, would have needed a complex social organisation, leadership, and detailed logistical planning for gathering supplies, construction materials, and coordinating voyages, an incredible achievement. They developed sophisticated knowledge of seasons, animal behaviour and plant cycles that allowed sustainable living without exhausting the land. They had a deep ecological intelligence and developed a long term relationship with the nature that surrounded them.

Just to put things in perspective, when the first humans reached what is now Australia, no Homo sapiens had yet reached what is now Europe. That would happen only 20’000 years later.

Once on the massive landmass of Australia, the early Aboriginal settlers rapidly spread and adapted to the continent’s immensely diverse environments—from the lush rainforests of the north to the arid deserts of the interior and the colder regions of the south. Within a few millennia, they had occupied almost every corner of Australia and Tasmania.

The period immediately following the arrival of humans and before they developed a very sustainable management of the environment, is closely linked to one of the most significant ecological events in Australia’s history: the extinction of the megafauna. The largest animals had survived for millions of years without predators and were not afraid of Homo sapiens, who probably appeared to them as innocent little apes, which led to their rapid demise. This, coupled with the widespread use of controlled burning (fire-stick farming) by Aboriginal people to manage the landscape, dramatically altered the vegetation structure, favouring fire-resistant species and in part destroying the food sources required by the large, specialised megafauna. Over time, the Aborigines did however, manage their environment in a very wise and ecological way.

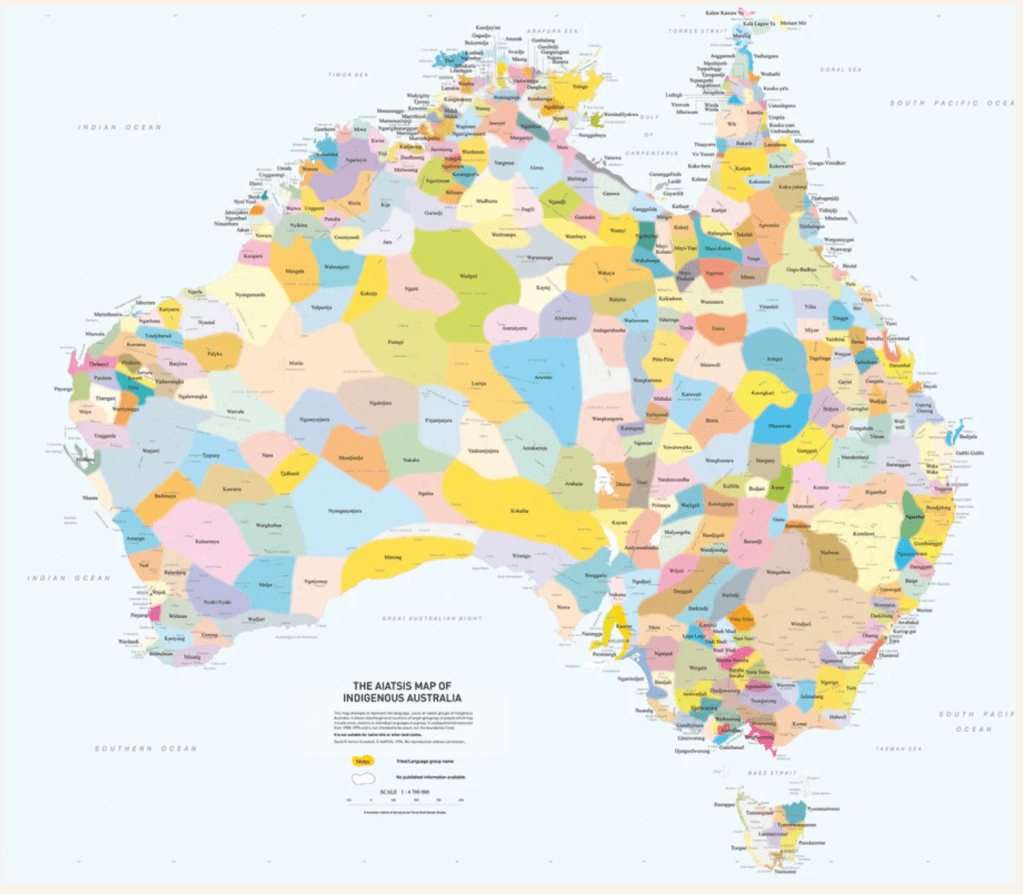

The isolation of Australia and Tasmania’s people, coupled with adaptation to varied environments, led to the development of hundreds of distinct Aboriginal nations, languages, and cultural practices. Before European contact, there were an estimated 250 separate languages and over 500 clan groups, making it the oldest continuous living culture on Earth.

Aboriginal society

The foundational principle of Aboriginal societies in Australia is referred to as “the Dreaming”. It is the key spiritual and cultural basis on which all Aboriginal peoples define and live their lives to this day. It’s not “a dream” in the Western sense — it’s a living reality that weaves together time, place, ancestry, law, and identity.

Dreams in the sense that we define them in the West, do play a role in Aboriginal societies. But they are perceived as just one of the ways in which individuals can access spiritual journeys, where individuals receive guidance, revelation, or confirmation of sacred knowledge from their ancestors.

Country, political structure and law

Australian Aboriginal societies were not unified under a single government but were organised into distinct, autonomous groups.

The fundamental unit of organisation within each group (or “Country”) was the clan or family group, based on strict rules of kinship. Kinship defined every person’s relationship to every other person, dictating whom they could marry, whom they must help, and their responsibilities towards the land. This complex system functioned as the political and social blueprint for existence.

For Australia’s Aborigines, Country (capital “C”) encompasses everything. It includes both living and non-living elements. It holds everything within the landscape, including Earth, water and the sky, as well as people, animals, plants, and the stories that connect them. Country relates to the nation, cultural group and region that Aboriginal people belong to, yearn for, find healing from and will return to. Country is the literal place of origin for Aboriginal peoples. Aboriginal peoples’ deep and personal relationships with Country are expressed in multiple ways. The lore of Country is expressed through songlines, stories, art and ceremony. Language, including the names of Aboriginal groups and place names, are another means of expressing relationships with Country.

Governance was historically based on customary law, passed down orally through the generations. There were strict rules for hunting, gathering, and caring for specific territories, as well as procedures for settling conflicts and punishing offenses, often involving the entire community.

Authority was not centralised but dispersed. Leaders were typically Elders (both men and women) who had attained deep knowledge of customary law, ritual, and history. Leadership was based on wisdom, skill, and knowledge of the sacred, not hereditary power or coercion.

Spiritual beliefs

The defining aspect of Aboriginal spirituality is connection to Country. The land is not property or territory, the way we see it in the West; it is a living, spiritual entity that is the source of all life.

Importantly, people belong to their Country, not the other way around. They are responsible for its care and preservation, which is a spiritual obligation. In return, the Country sustains them physically and spiritually.

Aboriginal spiritual beliefs hold that a newborn’s spirit does not originate at the moment of birth, but pre-exists in the land and arrives in the mother during the time of conception or, more commonly, during the pregnancy. The spirit is thought to enter the mother’s body in a variety of ways, such as when the mother consumes a food (a plant or animal) or while the mother is near a sacred place. Or the spirit may appear to the mother in a dream, signalling its desire to be born.

The location where the spirit enters the mother becomes the child’s spiritual birthplace. This site establishes the child’s lifelong spiritual duties to that specific portion of land, creating a deep and personal connection to Country.

Songlines

Aborigines had no written language. But they had Songlines, which described in great detail vast pathways that crisscross the continent, following the exact routes taken by Ancestral Beings during the Dreaming.

The songs describe specific landmarks, water sources, and important resources along the path. The songs, handed down through generations, contain encyclopedic knowledge of history, law, geography, and ecology. Singing the song correctly is literally retracing the path of the Ancestors and keeping their creative power active.

Examples of Songlines include the 3,500-kilometer route from the central desert to the eastern coast, the journey of the Rainbow Serpent, and local paths like the Yarra River Songline.

These ancient Aboriginal routes are memorised through songs, art, and ceremonies that trace the steps of creator spirits and connect people to the land through landmarks, geography, and astronomy. By singing a song cycle in the appropriate order, an Aborigine explorer could navigate vast distances, often travelling through the deserts of Australia’s interior (a fact which amazed early anthropologists who were stunned by Aborigines that frequently walked across hundreds of kilometres of desert picking out tiny features along the way without error).

Ceremonies and Rites

Ceremonies were vital for keeping the aboriginal culture alive and maintaining the spiritual health of the community and the land.

These were and for certain communities still are, general cultural gatherings involving singing, dancing, and body painting, often used to re-enact Dreaming stories for cultural education and entertainment.

One of the most important ceremonies involved initiation rites, marking the transition from childhood to adulthood, transferring sacred knowledge, often over many stages and years. These rites confirmed an individual’s place and responsibilities within the kinship system and their Country.

Other rituals performed at sacred sites encouraged the reproduction of a particular species or to renew the fertility of the land.

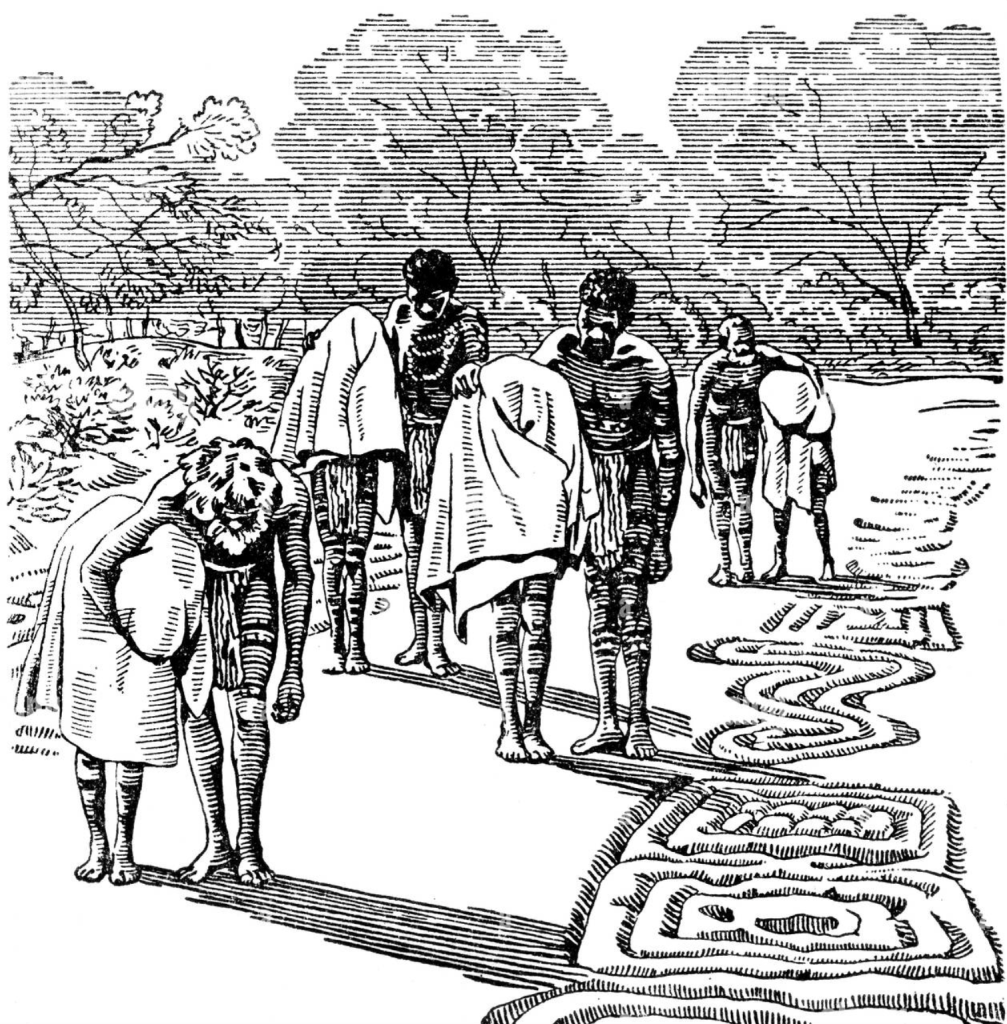

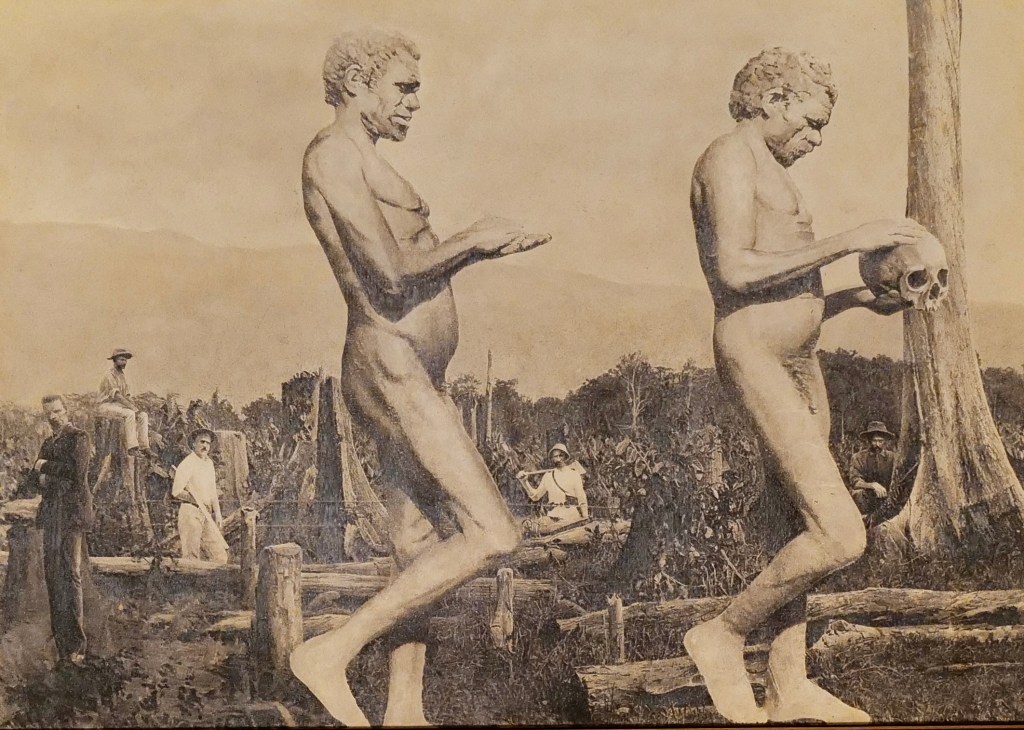

Example of a Bora Ceremony, a traditional Aboriginal ritual for boys, marking their transition to manhood. The name “Bora” also refers to the ceremonial grounds where the rituals took place, which typically feature two rings of hardened earth connected by a path. During the ceremony, which could last for weeks, boys were taught sacred songs, dances, and tribal lore, and underwent physical rites like scarification, circumcision or extraction of one of the frontal teeth.

Aboriginal art

Aboriginal art is the visual expression of the Dreaming (Dreamtime) and of Customary Law passed down through millennia. It is considered the world’s oldest continuous art tradition.

Aboriginal art is fundamentally sacred and instructional, not purely decorative. It serves as a vital tool for history, education, sacred geography, and spirituality. Every painting, carving, or rock etching is a visual record of the Ancestral Beings’ journeys across the land, recording the location of sacred sites, water sources, and resource management areas. The designs are often layered with meaning, communicating complex meanings and responsibilities for the land’s custodians. Many powerful designs are restricted to certain initiated men and women – so we, the today’s viewers will never completely know or understand the true meaning of this art.

In a non-literate society, as the Aboriginal world was prior to the arrival of Europeans, art served as a form of “title deed” or documentation, proving a clan’s spiritual and legal ownership of a specific territory and its associated Dreaming stories.

Many paintings use an overhead or “bird’s-eye view” perspective, making them function like maps. They depict landscapes, waterholes, paths, and camps using circles, lines, and arcs.

Death

As is the case in many other indigenous peoples, death was seen as a transition rather than an end. The body’s spirit returned to its Country or ancestral site to be reunited with Ancestral Beings, ready to be reincarnated into a descendant. This completed the cycle of creation established in the Dreaming.

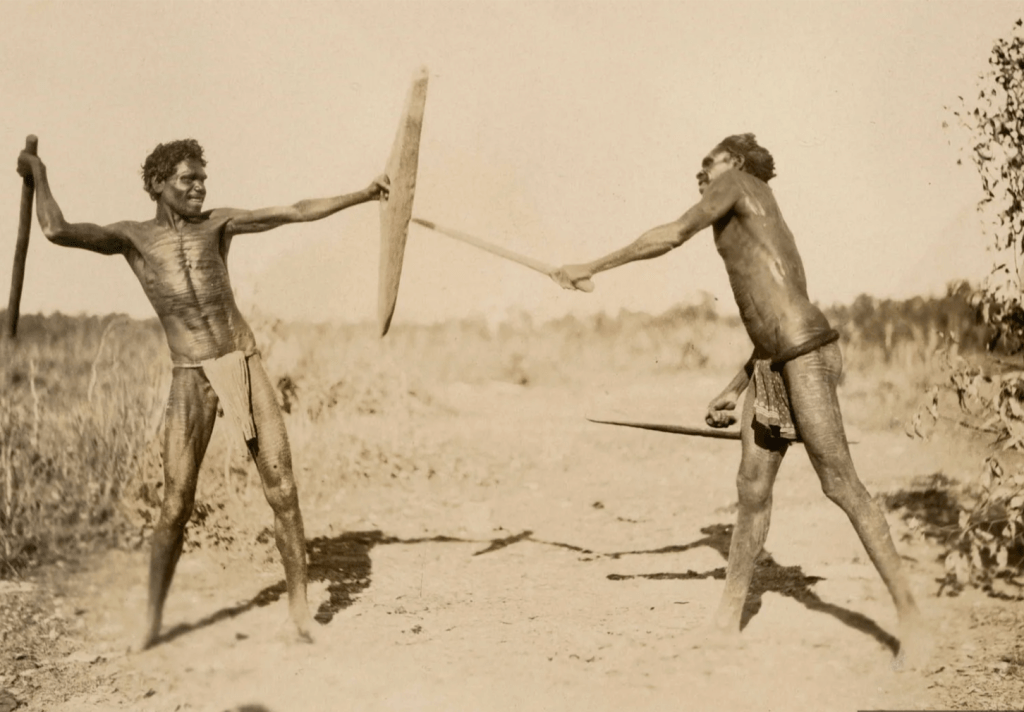

Conflicts and war

There were no disputes over land in pre-European Australia, since the aborigines did not consider land an ownable or tradable resource (it was the land that owned humans, not vice-versa). So, unlike large-scale, territorial wars common in European history, conflicts in Aboriginal Australia were generally localised, ritualised, and centred on specific grievances.

The most common cause was the need to enforce Customary Law or seek retribution (vengeance) for a serious offense. Grievances often included perceived acts of sorcery, unauthorised entry into sacred sites, breaking marriage rules, or insulting an Elder. Other disputes related to the abduction or elopement of women, which were seen as severe breaches of the kinship system and marriage laws. Or conflicts could arise from failures in performing rituals correctly, which were believed to cause spiritual or ecological harm to a community.

Dispute resolution mostly involved ritualised fighting. A common scenario involved a formal gathering where the aggrieved party would launch spears or boomerangs at the offender, who was typically obligated to stand their ground (often protected by a shield) until the debt was considered paid. The aim was often to inflict a non-lethal wound rather than to kill, thereby restoring balance and concluding the grievance under Customary Law.

Aboriginal conflict resolution in Australia was designed to ensure that the necessary retribution was carried out to re-establish social and spiritual balance, rather than to annihilate the opposing group.

Agriculture in Aboriginal Australia

James Cook, the first European to spend time in Australia, described the Aborigines in 1770 as wandering, primitive “hunter-gatherers”, with a carefree existence, and no knowledge of agriculture or husbandry.

He couldn’t have been more mistaken.

Aboriginal people used controlled, frequent land burning to clear old growth and promote new, nutrient-rich grasses that attracted kangaroos and other game, as well as to ensure the health and continued productivity of staple food plants. This practice did alter the landscape, but managed ecosystems in a way that maximised food availability.

In resource-rich areas, such as the wetlands of the Northern Territory, aborigines would regularly harvest wild yams and roots but would replant the head or top part to ensure the tuber regenerated for the next season. They would also manage areas of favoured grasses like nardoo and certain yams, clearing competitor species to increase yields.

The Gunditjmara people in southeastern Australia developed an extensive, permanent system of weirs, channels, and traps around Lake Condah to harvest eels. This system of aquaculture involved manipulating volcanic flows to create permanent ponds and channels that funnelled eels, ensuring a long-term, fixed food production system.

Other Aborigines developed complex methods for detoxifying starchy foods like the cycad palm seed and processing grass seeds into flour for baking (e.g., nardoo), which required grinding stones and long-term storage, yielding a stable food base beyond daily gathering.

Economic life and trade

Aboriginal economic life was based on the principles of reciprocity, resource management, and social obligation, rather than accumulation and profit.

Vast, intricate trade routes extended across the continent, covering thousands of kilometres. These networks were essential for the distribution of specialized materials. Key commodities included ochre, pipes, stones, feathers, shells, spears and ceremonial objects. Trade was often embedded within ceremonial exchange cycles that reinforced social ties, solidified alliances, and established relationships between distant groups.

Resource management and labour

While all people contributed to food gathering, there was often specialization based on age, gender, and spiritual knowledge. Men were generally responsible for hunting large game and ritual activities, while women focused on gathering plant foods, smaller animals, and often preparing foods.

The economy relied on the principle of reciprocity (mutual gift-giving). Sharing resources and food was a social obligation and a form of social security, ensuring that everyone in the kinship network was cared for, especially during times of scarcity.

Economic rights were based on spiritual custodianship of land. Clans owned the spiritual rights to the resources within their Country, and access to those resources was managed according to Customary Law and kinship ties. There was no individual land (or other) ownership.

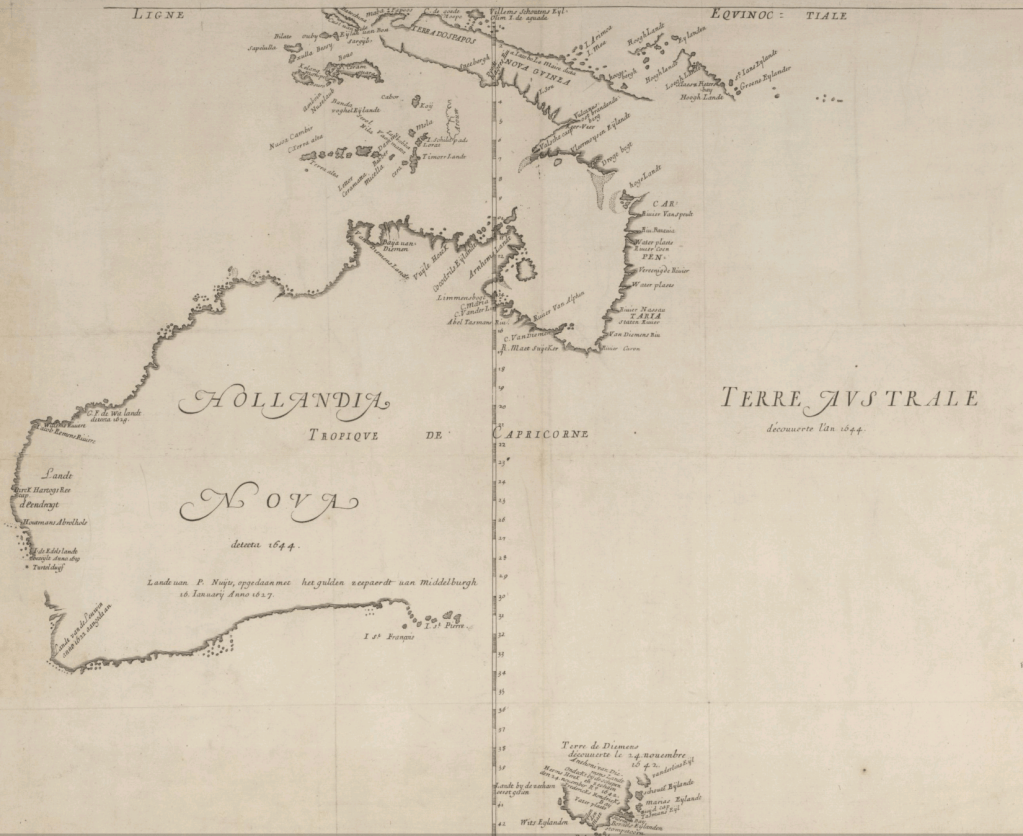

The European invasion

In the early part of the XVIIth century, Dutch sailors stopped in western and southern Australia and Tasmania and mapped parts of it, but no settlements were created.

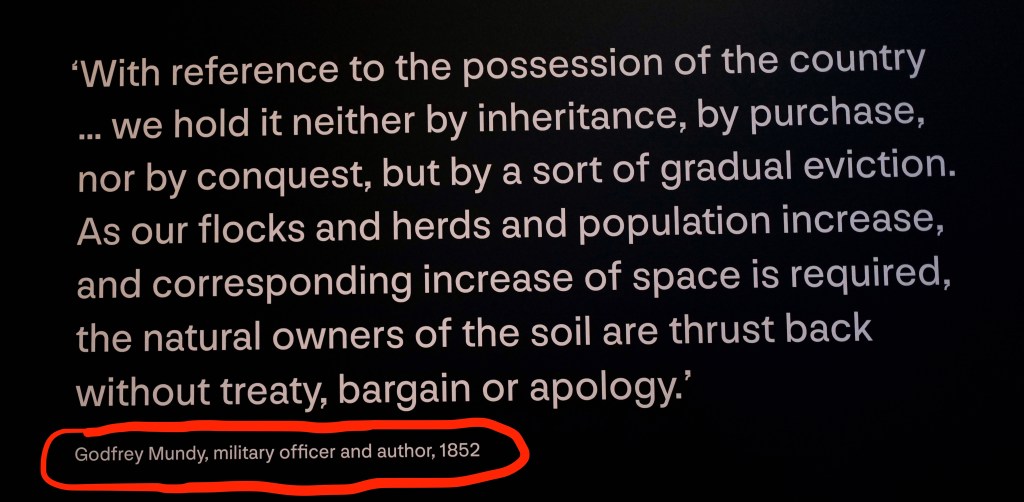

In 1770 British navigator James Cook charted the eastern coast of Australia and, claiming it to be terra nullius (“land belonging to no one,” despite seeing and meeting Aboriginal inhabitants), formally named it New South Wales and claimed it for Britain. But it was only in 1788 that Britain formally set up a colony in what is now Sydney.

The world’s oldest civilisation, which had survived and blossomed for tens of thousands of years in harmony with nature, that included sophisticated spiritual beliefs, a peaceful livelihood and a structure of ecologically just land management systems, was literally wiped out within a few decades.

The arrival of the British was initially responded to by the Aborigines with curiosity and even benevolence, but quickly degenerated into widespread and often brutal conflicts.

The core driver of the conflict was the seizure of land for farming, grazing, and settlement by the British settlers. As the colonies expanded outwards from Sydney, they encroached on the traditional Country of various Aboriginal nations, directly violating the spiritual, economic, and cultural foundation of Aboriginal life.

The British response was often disproportionate and characterised by official and unofficial massacres of Aboriginal people. Massacres and incarcerations were used as punitive actions against perceived threats or to clear land for settlement.

Following the arrival of Europeans, the Aboriginal population suffered a catastrophic and rapid decline due to a combination of factors, primarily disease and frontier conflict. The most immediate killer was disease. A major smallpox epidemic, likely arriving with the First Fleet, which arrived in 1788, devastated the Aboriginal population around Sydney and spread inland within the first few years. Death rates reached 90% in some areas. In addition, ongoing conflict and deliberate massacres as Europeans seized land also contributed significantly to the death toll.

The Aboriginal population is estimated to be have been about 750’000 in 1788. A few decades later, it had been reduced to a mere 90’000.

Massive environmental mismanagement

Not only the inhabitants were devastated, the environmental impact of European colonisation went far beyond the immediate conflict and involved severe land mismanagement that degraded Australia’s unique ecosystems. The loss of traditional Aboriginal management practices was a key factor in this degradation.

European settlers introduced millions of hard-hoofed livestock, such as sheep, cattle, and horses. The soft, ancient Australian soils were not evolved to withstand the continuous, high-pressure impact of hard hooves, particularly in the arid zones (nearly all the native species of Australian animals have light and wide spread feet and many of them hop around, which means that they don’t put a strain on the soil). This led to soil compaction, reducing water infiltration, and massive erosion, stripping the topsoil necessary for regeneration.

European farming was based on methods successful in the temperate climates of the Northern Hemisphere, which were fundamentally unsuited to Australia’s ancient, nutrient-poor soils and erratic rainfall.

Clearing vast tracts of deep-rooted native vegetation (like Eucalypts) to make way for shallow-rooted crops (like wheat) or pasture, raised the water table. This brought dissolved salts—naturally occurring in the soil—to the surface, poisoning the land in a process known as dryland salinity. The introduction of intensive grazing and cropping quickly depleted the fragile soils, locking farmers into a cycle of heavy reliance on artificial fertilisers to maintain productivity.

In addition, settlers deliberately or accidentally introduced numerous invasive species that outcompeted native flora and fauna. The introduction of rabbits led to a catastrophic environmental disaster, as they devoured native grasses and seedlings, competing directly with native marsupials. Foxes, introduced for sport, became a dominant predator that decimated native ground-dwelling fauna. European crop seeds and pasture grasses displaced native vegetation, altering habitats and fire regimes. In the rare sources of water in the deserts, cows peed and defecated, often poisoning the sources.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal people used frequent, small-scale, cool burns to manage the landscape. This created a mosaic pattern of burnt and unburnt country. This process promoted the growth of fresh, nutritious forage for game, prevented the build-up of massive fuel loads and minimised the risk of destructive, high-intensity bushfires.

However, the British settlers mostly prohibited Aboriginal burning practices, fearing for their wooden structures and stockyards. This allowed huge amounts of dry, dense undergrowth to accumulate. The loss of cool, controlled burns led to infrequent but catastrophic mega-bushfires that destroyed vast areas of forest and permanently altered sensitive ecosystems, proving far more damaging than the traditional burning practices.

In short, European land practices disregarded the unique ecological needs of the Australian continent, replacing a sustainable, many millennia-old management system with one that prioritised short-term resource extraction, leading directly to significant and often severe environmental problems.

Australia today

During our 5-week visit, we questioned many Australians about their history, in particular the destruction of the Aboriginal lifestyle and the widespread environmental mismanagement that followed the European settlement.

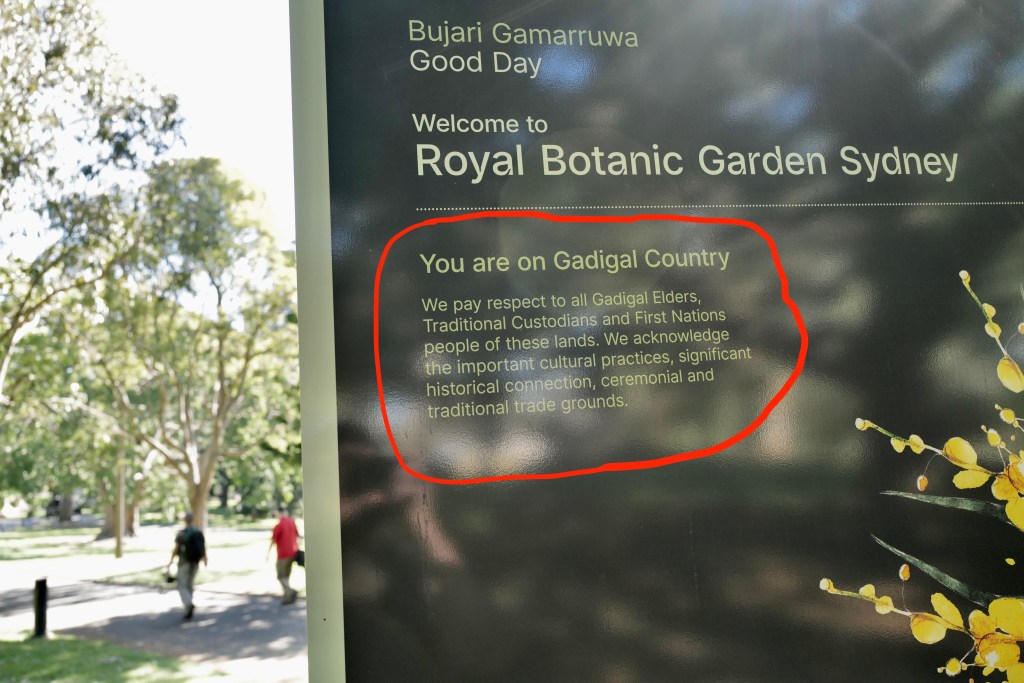

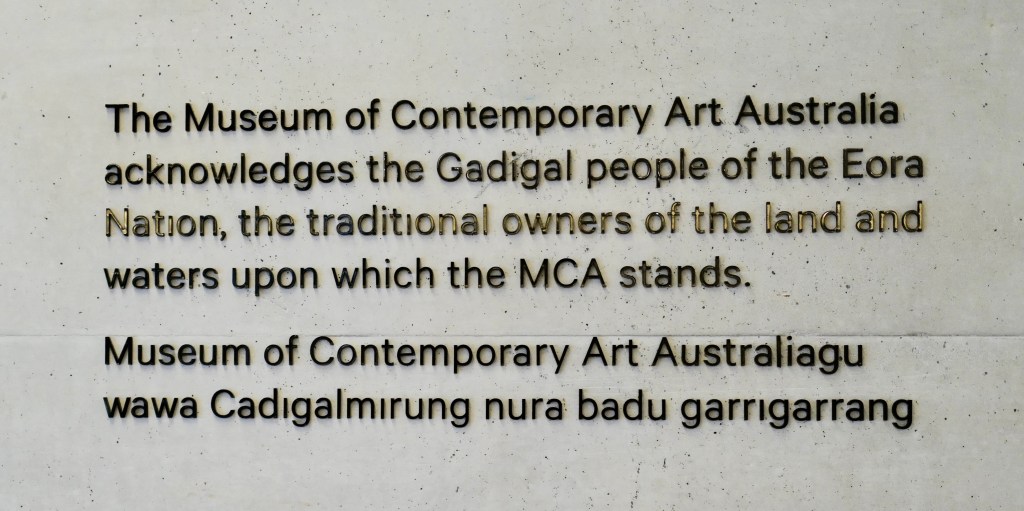

We found a broad consensus that these historical actions caused immense harm. There is now a high level of recognition and regret regarding the destruction of Aboriginal life and culture. The prevailing view acknowledges that colonisation led to systemic dispossession, violence, and cultural devastation. This is publicly recognised through annual events like the National Sorry Day and the increasing acknowledgment of Invasion Day on January 26th (a reminder of the day in 1788 when the first British settlers arrived).

In 2008, on behalf of the Australian parliament and governments, past and present, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offered a very public and sincere apology to the Aboriginal people for the brutal treatment they received by Europeans between 1788 and 1970.

Most Australians support the general goal of reconciliation, which aims to build better relationships between the wider community and the few remaining Aboriginal peoples. Beyond this, there is a growing widespread respect and interest in Aboriginal culture, art, and history, with programs in education, media, and tourism actively promoting this understanding (the excellent 2008 TV documentary series First Australians chronicles the history of Australia from an Aboriginal perspective, focusing on the collision between the world’s oldest living culture and the British Empire).

There is also an increasing acknowledgment that European land practices were ecologically destructive and that traditional Aboriginal knowledge is vital for the future. This ancient knowledge is now actively being incorporated into modern land and fire management strategies to combat recurrent and often catastrophic bushfires.

Australia today struck us as a truly welcoming melting pot of nations. We met people from dozens of countries who have made this distant nation their home. They all had the same comment, that the Australians have welcomed them and that the relaxed and happy environment provided them with a great lifestyle and an optimistic view of the future.

Sydney

Sydney is one of the world’s most beautiful cities we have ever seen.

What makes it truly fascinating is the incredible blend of urban sophistication, iconic architecture (starting with the world-famous Opera House), and stunning natural beauty.

The city is built around one of the globe’s finest natural harbours and is widely spread out, offering most people beautiful views of the sea. Sydney boasts over 100 beaches, making coastal lifestyle a part of daily life and a core part of the city’s identity.

For foodies, Sydney is a fantastic destination, offering authentic international cuisine from all over the world. You can easily find amazing and authentic Asian food in areas like Chinatown, Thaitown, and Koreatown, alongside vibrant Greek, Vietnamese, and Lebanese communities. The city is also famous for its high-quality, gourmet coffee scene.

Sydney is also exceptional because its natural environment isn’t just near the city, it’s woven directly into the urban fabric, creating a remarkable blend of steel and sea, concrete and coastline.

Finally, the many museums, including the Museum of Contemporary Art, the White Rabbit Gallery, the Museum of Sydney and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, make Sydney a great cultural hub.

Lord Howe Island

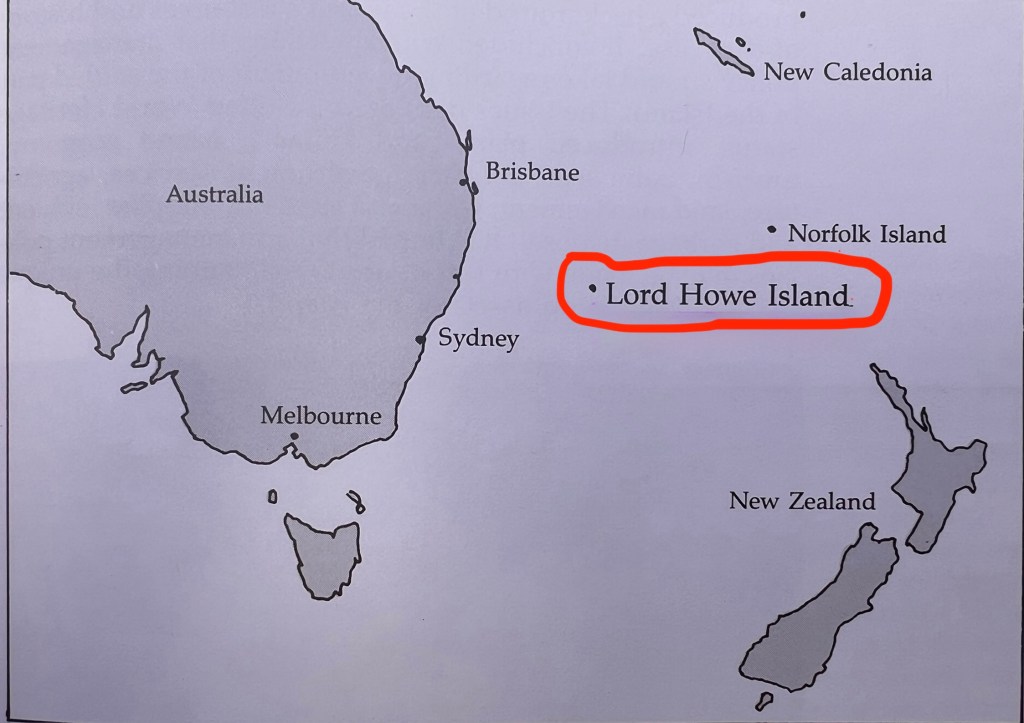

A tiny island located in the middle of the sea separating Australia from New Zealand, Lord Howe Island is a true jewel, which many people in Australia have heard about, but few have actually visited.

Part of Lord Howe’s attraction is the fact that access is severely limited. The island accepts only 400 tourists at any time, which means that when you are there, you mostly feel on your own.

The golden sun alludes to the warmth and friendliness of the islanders and the silver rays are seen shimmering on the crystal blue waters of the surrounding Pacific Ocean. Silhouetted against the sun are the striking volcanic features of the island.

Lord Howe’s isolation and the fact that it was only settled by humans very recently, means that you encounter there a highly endemic range of flora and fauna, and a uniquely preserved marine environment. This, combined with spectacular volcanic landscapes and dozens of untouched beaches, makes a true paradise for walkers and hikers.

Sir David Attenborough described the island as “so extraordinary it is almost unbelievable.” We agree with him!

Queensland’s Scenic Rim

Situated about 2 hours by car from Brisbane, is Queensland’s Scenic Rim. It’s a perfect area for wildlife viewing, great food and hiking.

Byron Bay and surrounding areas

If you like long walks on beaches, we cannot imagine a better place than the area surrounding Byron Bay.

This, accompanied by a famously relaxed, bohemian culture, makes the area a great destination for a farniente break.

Cape Byron is also a great place from which to view marine wildlife. Between May and November, the area becomes a prime location for whale watching as humpback whales migrate. For a closer experience, you can take a sea kayaking tour to paddle alongside dolphins and turtles, or dive/snorkel at the protected Julian Rocks Marine Reserve.

Melbourne

This dynamic and culturally rich city is often, with reason, ranked as among the world’s most liveable cities.

Beautifully located by the sea, Melbourne has an artsy feel to it and a vibrant artistic and food scene. Many areas are packed with hidden bars, chic cafés, boutique fashion stores, and world-renowned vivid street art and graffiti, essentially turning the city into a giant outdoor art gallery.

Known as the “Cultural Capital of Australia,” Melbourne boasts a vibrant entertainment and theatre scene, including major institutions like the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) in Federation Square, as well as numerous theatres hosting major productions.

Melbourne is also called the “sports capital of Australia,” hosting a calendar of world-class events including the Australian Open Tennis tournament and the Formula 1 Australian Grand Prix.

Despite its bustling city centre, Melbourne is rich in green spaces, including the magnificent Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Flagstaff Gardens, and Fitzroy Gardens, offering tranquil escapes.

If you don’t mind the rapidly changing weather, and that for most of the year it’s quite cold and windy in Melbourne, it’s truly a magnificently liveable city!

Tasmania

At the very south of Australia, the hardly inhabited island of Tasmania is all about pristine wilderness, unique wildlife, and a globally celebrated food and art scene.

The island is renowned for having some of the purest air and cleanest water in the world, which contributes to its incredibly fresh produce and crisp atmosphere.

We spent a week in Tasmania, but would have easily stayed at least twice as long!

Hobart

Hobart, Tasmania’s main settlement, is Australia’s second-oldest capital. We enjoyed the small roads filled with beautiful XIXth century buildings, the Saturday market, Mount Wellington and, as elsewhere but especially in Tasmania, the ubiquitous oysters.

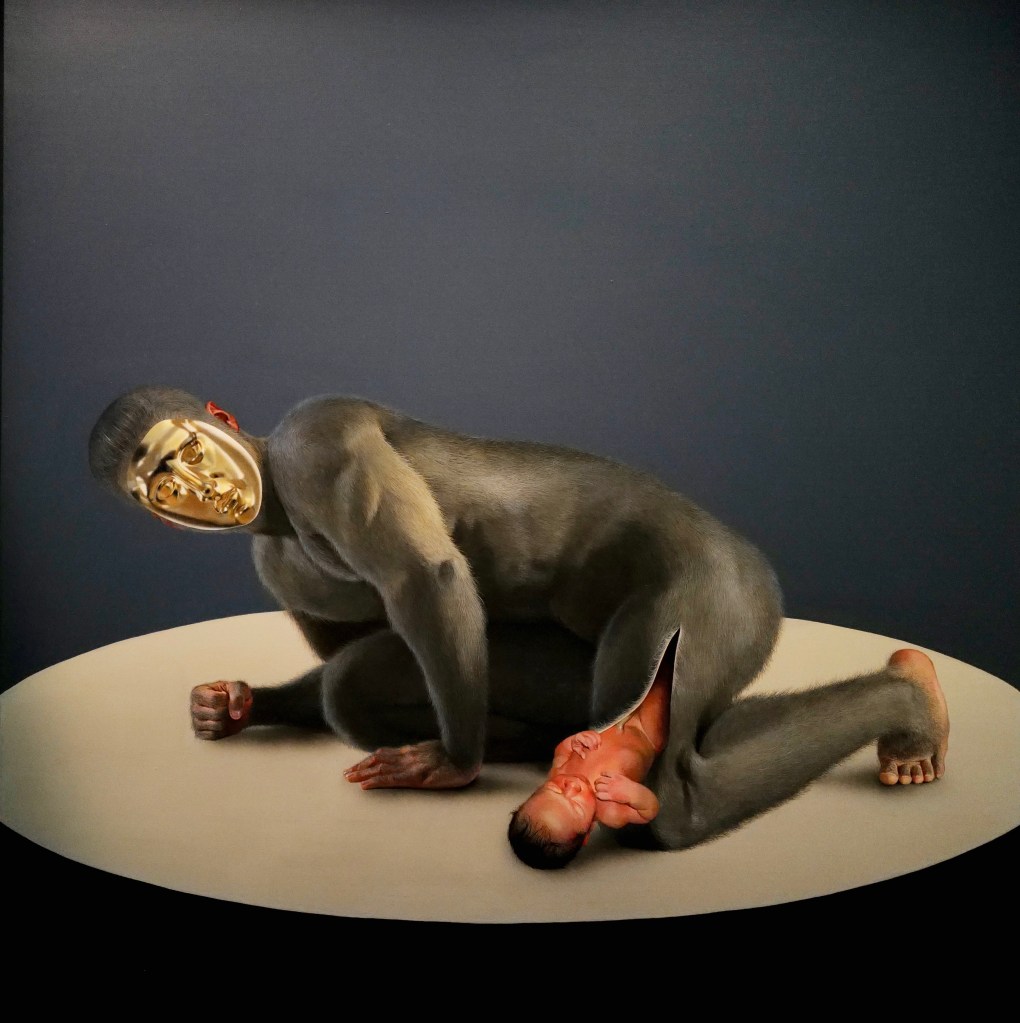

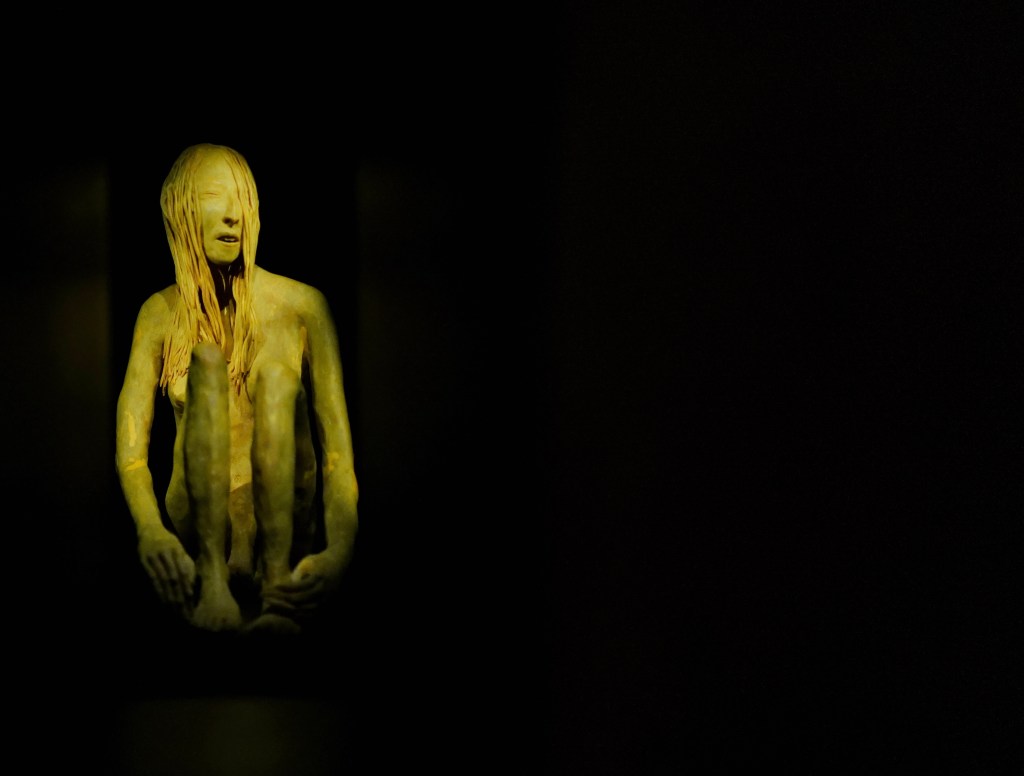

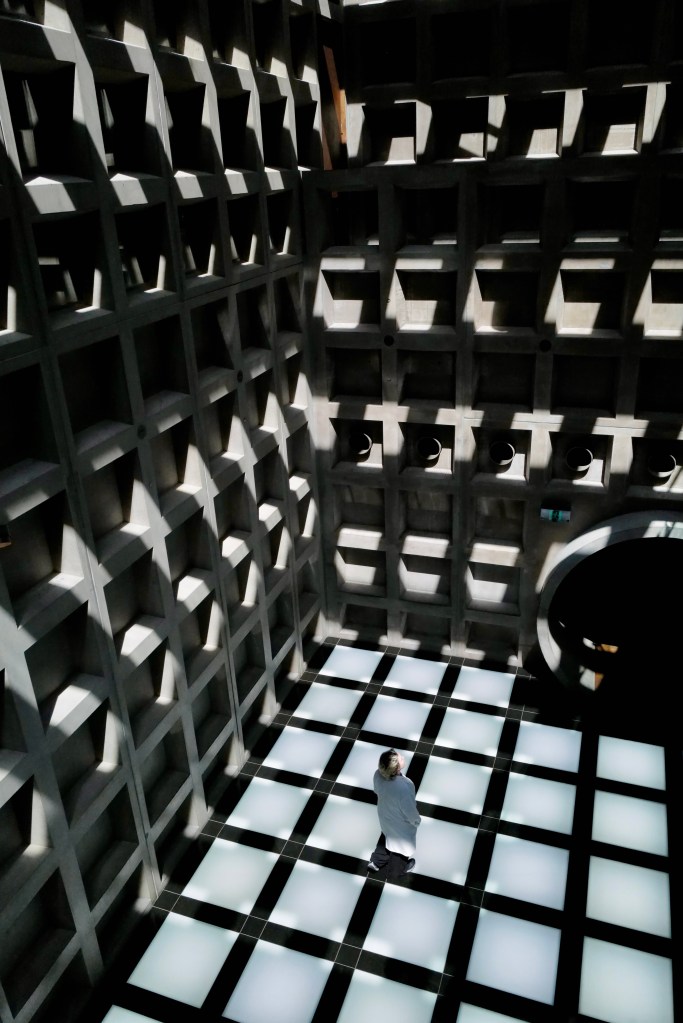

A special mention goes to MONA, the city’s magnificent art museum. Who would have thought that at the very end of the world we would discover what is, we think, the most spectacular art museum we have ever seen? This privately-funded museum is boundary-pushing and includes a controversial collection of ancient and modern art (of which only 4% is exhibited at any time). MONA is an experience in itself, from the ferry ride up the Derwent River to the subterranean architecture and the cutting-edge material shown.

At MONA, we had the great fortune to be taken on a private, after-hours tour, by David Walsh, the founder, preceded by (did you guess it?) by an oyster-filled lunch on his private rooftop. It was unforgettable.

Freycinet

About a 2 hour scenic drive from Hobart is Freycinet, a totally unspoiled area of Tasmania, lined with secluded coves and beautiful beaches contrasting white sand with granite outcrops and blue sea.

During our time in Freycinet, we visited an oyster farm. The region’s super clean waters, combined with sustainable practices, produce some of Australia’s highest-quality oysters. Partially submerged, we nevertheless succeeded in eating at least two dozen oysters each.

It was in Freycinet that we took a 12 km-long path, originally built by the Toorernomairremener people about 8’000 years ago. As we followed in their footsteps, only stopping here and there in the areas built for spiritual (and surely also enjoyment) purposes, we could feel their positive energy and their love for this, their magnificent Country.

Thank you, once again, for this detailed report. Having also visited Tasmania, I can only agree with you: it’s a island worth staying longer and when I visited, a few years after the Voietnam war was over, it was also haven for Hmong families for Laos… Re Australia and Aborigenes, you write :”we found a broad consensus that these historical actions caused immense harm. There is now a high level of recognition and regret regarding the destruction of Aboriginal life and culture… This is publicly recognised through annual events like the National Sorry Day and the increasing acknowledgment of Invasion Day on January 26th”. In my modest view, this is cosmetic bull… Yes, “authorities” and white collar educated folks express “regrets”, but many many Australians WASPS’s abd those you don’t meet in the lovely part of cities, but in the rougher areas and in the bush are racist. And dont ming expressing their disgust regarding Aborigenes, Africans, Pacific Islanders, Chinese, Jews, etc. And the immigration policies of Australia also reflect this attitude. And what about the concentration camp (officially “detention center”) in Nauru ? So yes, great country to visit but for a warm welcome, you are better off as a caucasian well educated person with some money to spend rather than a Melanesian visitor from Fiji on a budget…

LikeLiked by 1 person